God and Nature Summer 2023

By Marline Williams

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.” Genesis 1:1,2

Didn’t you assume Victorian Bible-believing Christians were anti-Darwin? I did, until I read the modest First Lessons in Geology by Alpheus Spring Packard Jr.

Packard (whose penname was a prudent A.S. Packard Jr.) was professor of Zoology and Geology at Rhode Island’s Brown University from 1878 until 1905, when he passed to his reward. His pocket-sized 1882 text comprised part of my year of 19th-century Chautauqua Literary and Science Circle (CLSC) readings* and was designed to accompany the Chautauqua Scientific Diagrams Series No 1 (Geology). Alas, I was unable to dig up said diagrams and had to be content with imagining the soggy prehistoric shores as described by Packard in vivid “You Are There” detail.

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now the earth was formless and empty, darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters.” Genesis 1:1,2

Didn’t you assume Victorian Bible-believing Christians were anti-Darwin? I did, until I read the modest First Lessons in Geology by Alpheus Spring Packard Jr.

Packard (whose penname was a prudent A.S. Packard Jr.) was professor of Zoology and Geology at Rhode Island’s Brown University from 1878 until 1905, when he passed to his reward. His pocket-sized 1882 text comprised part of my year of 19th-century Chautauqua Literary and Science Circle (CLSC) readings* and was designed to accompany the Chautauqua Scientific Diagrams Series No 1 (Geology). Alas, I was unable to dig up said diagrams and had to be content with imagining the soggy prehistoric shores as described by Packard in vivid “You Are There” detail.

So, how does Packard reconcile his belief in God and his belief in science? |

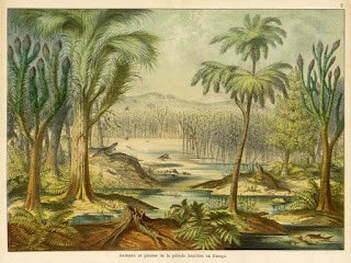

Because First Lessons had an intended audience of American students, Packard zeroes in on our primeval native heath. In the “America During the Silurian Period” chapter, he lovingly depicts American-grown prehistoric flora and fauna, drawing appealing word pictures of wooly mammoth herds frolicking while antediluvian urchins gaped in wonder. His is a very national geographic.

From his robust narrative, one pictures Packard a rugged chap in jodhpurs and a pith helmet, pickax at the ready, tramping through swampy fields and clambering over rocky mountainsides. (I’ve seen images of this fellow—his impressive beard could have qualified as a distinct eco-system.) Packard’s personal adventures are sprinkled throughout the book—volcano climbing (live, mind you), forest trekking, fossil spelunking. These boots-on-the-ground anecdotes reassure any dubious CLSC student of Packard’s street creds and, for the modern non-scientific reader, interject a frisky note of personality into this teeming morass of words.

In fact, Packard was the real deal. He helped found The American Naturalist, was a member of the American Philosophical Society (interestingly, Darwin was a fellow member, as were Pasteur, Edison, and our founding fathers highlights reel), and described hundreds of new species, many of them insects, some of which we must assume made it into his three-volume Monograph of the Bombycine Moths of North America. A product of his age and a testament to his upbringing, Packard was well-versed and fascinated with both the world of nature and the internal, spiritual cosmos.

By Victorian standards, Packard’s prose is restrained. By ours—well, let’s just say you may want take a refresher course in sentence diagramming before sitting down with this book and a mug of coffee. Under his rampant pen, the era’s signature literary flourishes unfurl like fragile Triassic ferns:

It is so simple an agent as running water rather than volcanic upheavals, which has, late in the world’s history, changed the face of nature, and adorned the earth with carved work, combining grandeur and sublimity with a delicacy and beauty of finish which elevates and informs the soul of man with the loftiest and finest feelings.

Most contemporary readers wouldn’t attempt that sentence without first tying a rope around their brain in case they lost their way.

Fledgling scientists with poetic souls (not an oxymoron in Victorian days) may have sent the author a note of approval after reading

…there swam schools of smaller, slighter ganoid fishes, whose silvery chased and fretted plates of enamel gleamed in the bright clear waters lit up by the torrid rays of a Devonian sun.

Read that last passage aloud. No, seriously. Listen to the lilt, the rise and fall of Packard’s poetry in motion. Ah, for our minds to be lit up by the torrid rays of the Devonian sun, rather than scrabbling darkly for unanswerable arguments with which to quell our opponents’ objections.

So, how does Packard reconcile his belief in God and his belief in science? He doesn’t even dignify the debate with an argument. Calmly, cheerfully, he asserts that anyone with even a modest amount of brains can tell from the evidence that the earth is zillions of years old. Like most 19th-century authors, particularly those tapped to write texts for the Chautauqua crowd, Packard presents his imaginative, exemplary scenarios with a fait accompli flair. As I have written, so it must have been done.

Professor Packard would find the current conservative Christian adherence to a six-thousand-year-old earth model to be hooey on a Jurassic scale. But, perhaps anticipating the animosity of future Darwin vs. Intelligent Design factions, the congenial professor presents a conclusion that not only tidies up loose ends, but stretches out a hand of peace towards each:

Such, then, is the story of creation. And when we contemplate the creative or evolutional force which is immanent in nature, who can logically deny that here we are dealing with the evidences of the existence of an all-pervading and all-wise Intelligence outside of the material world, the Origin and Creator of all things?

Packard’s passionate, patient, oddly peaceful observations express his convictions that some of God’s marvelous works remain “wrapt”—enclosed and enraptured—in dense obscurity. Is it any wonder he concludes this text with a question mark?

*See series introductory article in God and Nature, Spring 2023.

Marline Williams received her preliminary science education observing natural phenomena (read: star-gazing, cloud-watching, lizard-taming). She makes no claims of being a scientist, merely a writer who loves to string connecting threads between God’s word, classic literature, and the cosmos. Her most recent experiment: speculative collisions between 19th-century Chautauqua Literary & Scientific Circle authors and 21st-century science gurus. Her Bachelors and Masters in English Literature hail from Nazareth College and the University of Rochester, respectively, and she’s currently madly at work on a novel set during the 1970’s Jesus Revolution. Marline welcomes new friends and readers to www.MarlineWilliams.com.

From his robust narrative, one pictures Packard a rugged chap in jodhpurs and a pith helmet, pickax at the ready, tramping through swampy fields and clambering over rocky mountainsides. (I’ve seen images of this fellow—his impressive beard could have qualified as a distinct eco-system.) Packard’s personal adventures are sprinkled throughout the book—volcano climbing (live, mind you), forest trekking, fossil spelunking. These boots-on-the-ground anecdotes reassure any dubious CLSC student of Packard’s street creds and, for the modern non-scientific reader, interject a frisky note of personality into this teeming morass of words.

In fact, Packard was the real deal. He helped found The American Naturalist, was a member of the American Philosophical Society (interestingly, Darwin was a fellow member, as were Pasteur, Edison, and our founding fathers highlights reel), and described hundreds of new species, many of them insects, some of which we must assume made it into his three-volume Monograph of the Bombycine Moths of North America. A product of his age and a testament to his upbringing, Packard was well-versed and fascinated with both the world of nature and the internal, spiritual cosmos.

By Victorian standards, Packard’s prose is restrained. By ours—well, let’s just say you may want take a refresher course in sentence diagramming before sitting down with this book and a mug of coffee. Under his rampant pen, the era’s signature literary flourishes unfurl like fragile Triassic ferns:

It is so simple an agent as running water rather than volcanic upheavals, which has, late in the world’s history, changed the face of nature, and adorned the earth with carved work, combining grandeur and sublimity with a delicacy and beauty of finish which elevates and informs the soul of man with the loftiest and finest feelings.

Most contemporary readers wouldn’t attempt that sentence without first tying a rope around their brain in case they lost their way.

Fledgling scientists with poetic souls (not an oxymoron in Victorian days) may have sent the author a note of approval after reading

…there swam schools of smaller, slighter ganoid fishes, whose silvery chased and fretted plates of enamel gleamed in the bright clear waters lit up by the torrid rays of a Devonian sun.

Read that last passage aloud. No, seriously. Listen to the lilt, the rise and fall of Packard’s poetry in motion. Ah, for our minds to be lit up by the torrid rays of the Devonian sun, rather than scrabbling darkly for unanswerable arguments with which to quell our opponents’ objections.

So, how does Packard reconcile his belief in God and his belief in science? He doesn’t even dignify the debate with an argument. Calmly, cheerfully, he asserts that anyone with even a modest amount of brains can tell from the evidence that the earth is zillions of years old. Like most 19th-century authors, particularly those tapped to write texts for the Chautauqua crowd, Packard presents his imaginative, exemplary scenarios with a fait accompli flair. As I have written, so it must have been done.

Professor Packard would find the current conservative Christian adherence to a six-thousand-year-old earth model to be hooey on a Jurassic scale. But, perhaps anticipating the animosity of future Darwin vs. Intelligent Design factions, the congenial professor presents a conclusion that not only tidies up loose ends, but stretches out a hand of peace towards each:

Such, then, is the story of creation. And when we contemplate the creative or evolutional force which is immanent in nature, who can logically deny that here we are dealing with the evidences of the existence of an all-pervading and all-wise Intelligence outside of the material world, the Origin and Creator of all things?

Packard’s passionate, patient, oddly peaceful observations express his convictions that some of God’s marvelous works remain “wrapt”—enclosed and enraptured—in dense obscurity. Is it any wonder he concludes this text with a question mark?

*See series introductory article in God and Nature, Spring 2023.

Marline Williams received her preliminary science education observing natural phenomena (read: star-gazing, cloud-watching, lizard-taming). She makes no claims of being a scientist, merely a writer who loves to string connecting threads between God’s word, classic literature, and the cosmos. Her most recent experiment: speculative collisions between 19th-century Chautauqua Literary & Scientific Circle authors and 21st-century science gurus. Her Bachelors and Masters in English Literature hail from Nazareth College and the University of Rochester, respectively, and she’s currently madly at work on a novel set during the 1970’s Jesus Revolution. Marline welcomes new friends and readers to www.MarlineWilliams.com.