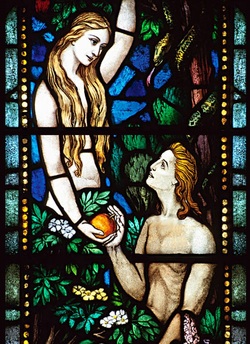

Is There Anything Historical About Adam and Eve?

by Mike Beidler

In 1887, my distant cousin, Jacob Hoke Beidler (1829-1904), published an extensive poem titled The Pre-Adamic Advent of Homo and Homodine on the American Continent: With Sequel. In his “prefatory proposition” that opened the poem, Beidler wrote: Jehovah’s everlasting love alone Gave life direct from His eternal Throne; Not evolution with creative force, Nor molten orb of light through heaven’s course. Despite disagreeing with Jacob in certain respects, I can’t deny he had a way with words. It’s a beautiful poem. As with many of the ideas, concepts, and doctrines to which we hold dear, it is never easy to disown or significantly change them. Yet, every once in a while, we are confronted with evidence to the contrary that requires us to rethink things, even cherished paradigms. In the case of Adam, my personal journey has become one of both rejection of the “biblical” Adam and subsequent re-embrace of the “historical” Adam—in essence, a heavily nuanced dismissal of the all-too-common conflation of terms biblical and historical. This statement is, understandably, disconcerting to some. Since taking leadership of the ASA’s DC Metro Section last January, I’ve had a number of opportunities to speak at various churches—including those of fellow ASA members—about the subject of the historical Adam as it relates to modern science. What has been extremely helpful to me in my preparations is the ASA’s decision to remain uncommitted to a particular view of origins (which would include the question of Adam) in favor of unity in the Body of Christ. The organization’s willingness to tolerate a wide range of views on such a controversial topic has helped me refine my approach and maintain a pastoral sensitivity to the concerns that many of my fellow Christian brothers and sisters have about the potential clash between science and our shared faith. While some in the audience remained uneasy with my conclusions, a vast majority appreciated the exposure to a different way of understanding Scripture, one that remained fully committed to the authority of Scripture in the Christian life. In the end, when they understand what I’ve actually rejected and what I’ve ultimately embraced in all its nuanced glory, they are typically put at ease. With that said, I’d like to relate briefly my story. My journey from young-earth creationism and its associated treatment of Genesis 1-11 as historical narrative akin to modern-day journalistic accounts began nearly a decade ago when I began to conduct personal research on biblical and scientific evidences for the old-earth creationist paradigm. Just prior to this period of discovery, I had successfully completed an international business degree program and obtained a heightened sensitivity to the power of cultural differences and the problems they can create when those differences are ignored or disrespected. I became increasingly aware that the biblical texts I was reading were written to a people with whom I had very little in common culturally; thus, I found myself increasingly uncomfortable with the lengths to which some Christians went to find concordance between biblical descriptions of creation and science. It seemed to me that I might have been guilty in the past of forcing a modern cosmological paradigm onto an ancient one, thus distorting the message of Scripture. It was at this time that I was introduced to the writings of Old Testament scholar John Walton from Wheaton College. His NIV Application Commentary on Genesis (Zondervan, 2001), along with his other works on ancient Hebrew thought and its shared cognitive environment with another ancient Near Eastern cultures (to include the assumption of a three-tiered cosmos) had a profound impact on me. While Walton’s works helped me discover deeper purpose and meaning in Genesis 1, I remained unconvinced that a non-concordist approach largely ceased at Genesis 2:4a. Having been recently convinced of mankind’s common ancestry with the rest of Earth’s flora and fauna through Daniel J. Fairbank’s Relics of Eden: The Powerful Evidence of Evolution in Human DNA (Prometheus Books, 2007), understanding the story of Adam’s creation as historical was not fitting neatly into the puzzle taking shape before me. Denis Lamoureux’s Evolutionary Creation: A Christian Approach to Evolution (Wipf & Stock, 2008) helped me immensely in understanding follow-on chapters of Genesis as etiological literature. In such works, affirming present-day realities—such as the sinfulness of mankind, the toil we must endure to provide for our families, and the ever-present clash of cultures—was more important to the Hebrews than the retrojective nature of the stories by which they explained such realities. To be sure, the literary constructs of the various stories in Genesis 2-11 are difficult to recognize without assistance. However, with Lamoureux’s help and that of other scholars such as Paul Seely and Peter Enns, I developed the ability to distinguish the core messages of these controversial biblical passages and tease them out of the limited cultural contexts in which they were embedded. This process of alternately immersing myself in an ancient paradigm and then viewing that paradigm from my modern perspective led me to accept the idea that God is an accommodationist more concerned about guiding his people into a closer relationship with him than the scientific accuracy of the paradigms he uses in doing so. Still, ancient cosmology is one thing; ancient anthropology is another. How extensive was God’s accommodation to his people? As I began digging deeper into my biblical studies, I began recognizing scientifically inaccurate paradigms reflected through the Hebrew and Christian scriptures: ancient biology such as species immutability {Gen 1:11-12, 21, 24-25) and preformatism (Gen 11:30; 25:21; Luke 1:7), ancient taxonomy (Lev 11:13-19), and ancient botany (Mark 4:31). How much of a stretch would it be that God would communicate his truths using ancient anthropology? Did it matter whether the biblical Adam truly existed? Would Adam’s non-historicity demolish the need for Jesus Christ’s historical acts of sacrifice and redemption? For me, I found the answer to these questions in the hermeneutical practices of Second Temple Judaism. At the same time I was struggling with the principle of divine accommodation, I was also struggling with how various New Testament authors used the Old Testament in their defense of Jesus as the fulfillment of ancient prophecy. I noticed that early biblical interpreters—including the authors of the New Testament—chose their biblical texts selectively to support their theological themes. At times, they even appeared to rip alleged prophecies in the Hebrew Scriptures right out of their original contexts and re-appropriate them in a manner that we today would find unacceptable (e.g., Matt 2:14-15; cf. Hos 11). I familiarized myself with midrash and pesher, two closely related approaches to interpreting Scripture common in Jesus’ day. In both of these, these interpreters would bring together different biblical texts in order to address contemporary issues, sometimes being extremely creative in the process (e.g., Paul’s apparently “inconsistent” use of Gen 13:14-16’s seed/offspring in Gal 3:16, 29). Such appropriations and reinterpretations of Scripture were acceptable in Second Temple Judaism and, in some Jewish schools of thought, were just as authoritative as the texts from which they were derived. While I wouldn’t use such hermeneutical techniques myself, like my embrace of God’s accommodative practices in terms of ancient scientific paradigms, I felt led to embrace his accommodation of non-Western, ancient ways of understanding and applying Scripture as a means of transmitting theological truth—such as Jesus’ divinity and identification as the Messiah—regardless of a biblical text’s original context. Which brings me to Paul’s use of the Old Testament in his discussion of the first and last Adams (see 1 Cor 15; Rom 5, 8). Because of the radicalness of Jesus’ crucifixion and subsequent resurrection, Paul’s subsequent use of the Old Testament became solely Christ-centered, resulting in a theology developed by means of re-reading the Old Testament through the lens of Jesus. Such theological constructs included the clear use of Adam as an archetype representing original humanity (Rom 5:14) and Jesus as an antitype representing what C. S. Lewis in Mere Christianity called the next step in human evolution (1 Cor 15:21-22). Keep in mind that, in writing to the churches in Corinth and Rome, Paul was not arguing for Adam’s strict historicity, for there was no competing anthropological paradigm. Neither was Paul arguing to establish the reality of sin and death, for both were (and are) demonstrable givens. Rather, Paul was arguing for the necessity of Jesus Christ as a remedy for humanity’s enslavement to sin. Paul was arguing that Jesus’ indisputable defeat of death gives us hope that our “eternal life” will continue beyond the grave! So where do I stand today on Adam? Given the scientific evidence, I no longer believe that Adam and Eve as described in Genesis 2-3 actually existed. Just as I don’t believe certain elements of “biblical” cosmology actually exist (e.g., the firmament of Gen 1:6-8), I believe a well-reasoned case can be made using both science and biblical hermeneutics that “biblical” anthropology is also inaccurate from a modern, scientific perspective. That being said, I still embrace the concept of an “historical” Adam. I’ll say it again: I believe Adam and Eve did and do exist as historical realities. From a modern anthropological perspective, points in the evolutionary development of the human species parallel the biblical Adam and Eve’s: our species, at one point, was “innocent,” eventually evolved the ability to make moral decisions, but nevertheless rebelled against God’s Moral Law. Likewise, from an archetypal perspective, the biblical Adam and Eve represent the human condition: their story is our story. I am Adam; you are Eve. We are born “innocent” (yet possessing the innate capacity for selfish behavior), we mature into an ability to make moral decisions, but we nevertheless rebel against God’s moral law. Whether one accepts the theological doctrine of Original Sin or (as I prefer) the scientific doctrine of Original Selfishness, the outcome remains identical: We are sinners in need of God. Regardless of sin’s exact origin—whether via rebellion in the Garden of Eden or rebellion against God’s Moral Law as a species during humanity’s evolutionary development—I recognize that sin is still quite real. Its presence in the human species is universal. Its presence is observable and repeatable. And our individual and collective sin still requires a remedy: the historical Jesus of Nazareth. |