On Knowledge and Information: Tales from an English Childhood

by Mike Clifford

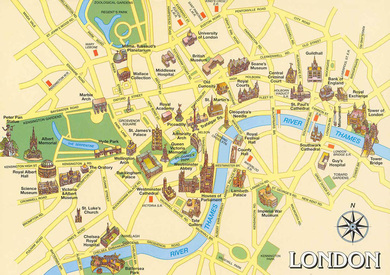

Growing up in Kent, the Garden of England, I attended a "selective school" – a state school which took the top 20% of students under its wings. Most of these schools in the UK are located in the South East and are called "grammar schools", but mine was different, and went under the splendid title: "Sir Joseph Williamson's Mathematical School". The school was founded in 1701 to produce young men with mathematical and engineering knowledge to work as naval architects in the nearby Chatham Dockyard. The dockyard closed in 1984, but the school remains, and after three hundred years, it has opened its doors to girls (but only to pursue sixth-form education). The school was very traditional, with many quaint customs, including prefects who wore straw boaters and generally lorded it over the younger boys. Punishments were often inventive and in the cruel and unusual categories, such as having to hold a book against a wall with one’s nose. One of the dullest punishments was to copy out the following phrase a set number of times. 'Knowledge is a steep which few may climb, but duty is a path which all may tread' Special attention had to be given to copying every word in the phrase 100% correctly - a common mistake was to write 'knowledge is a step..." rather than a "steep". Mistakes like this generally resulted in your lines being torn up before your eyes with the result of having to repeat the punishment. The origin of the phrase remained a mystery to me and, I suspect, to virtually everyone who copied out the lines, but on investigation, it appears that they come from the third volume of “Epic Of Hades” - a Dante-esque epic, which runs to three hundred pages, written by the Welsh nineteenth century lawyer, Sir Lewis Morris, who narrowly missed out on becoming Poet Laureate. Morris takes the reader on a guided tour of the Greek underworld, stopping off to hear from various Greek deities, who generally seem perhaps unsurprisingly to be rather unhappy with their lot. Morris himself appears to have attracted quite a lot of criticism in his day, being called “a Tennyson for children” and “the Harlequin Clown of the Muses” by some of his contemporaries. Edith Cooper wrote that “one is patient with him out of pity”. Patient, dutiful reading is indeed required to appreciate his work, which was regarded as somewhat ponderous, even by Victorian standards. I wonder if this is why the phrase was selected to be copied out as the punishment. Drawing a parallel with experimental work, although popular depictions of science concentrate on “eureka” moments, dutiful experimentation involving many laborious tasks may often be required to test hypotheses. The collection of information (data) is vital for the advancement of knowledge; at least if the knowledge is to be firm enough to withstand the scrutiny of peer review. We’ve all heard attractive theories espoused at conferences or even read them in draft journal papers which seem plausible, but aren’t entirely supported by data. I’ve frequently had to reel in students who want to see patterns in their data even when statistical tests expose the trends as little more than wishful thinking. But can knowledge ever trump information? In chapter nine of John’s gospel, the Pharisees’ scientific investigation of Jesus’ healing of a man who had been blind from birth raised many theological and practical questions. How could a “sinner” bring about healing? Where was the control sample? What experimental method was used? The man’s exasperated answer to the probing questions is not one that I can recommend as a response to referees’ reports on a journal paper, since it relied on knowledge rather than information: “Whether he is a sinner or not, I don’t know. One thing I do know. I was blind but now I see!” John’s gospel often emphasises the need for knowledge – gnosis – which, taken to an unhealthy extreme, can lead to theories that disregard information / data and rely on blind faith. In the scientific community there can be a tendency for theoreticians to distrust experimentalists and vice versa, with a Cartesian Dualistic approach resulting in conferences exclusively for “Theoretical Physics” and so on. In London, "knowledge" has a very specific meaning. Official London black cab drivers have to pass a very tough exam - "the knowledge" - which tests their memory of how to reach landmarks and streets within the capital and how to find the quickest way from A to B without the use of a Sat Nav. Gaining “the knowledge” can take many years, which may help us to understand the protests by taxi drivers over the threats posed by information technology such as the Uber and Hailo apps to their livelihoods. Here, information (technology) threatens to replace rather than to advance knowledge. So, when it comes to science, which is superior, information or knowledge? Can we have knowledge without information? We can certainly have information without knowledge. Einstein once said, “Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited to all we now know and understand, while imagination embraces the entire world, and all there ever will be to know and understand.” Imagination – the picturing of what might yet be is critical if knowledge is to advance beyond information-gathering. Or, according to Paul, “Now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.” So, perhaps knowledge isn’t the ultimate “steep which few may climb” but eventually we’ll be able to echo C.S. Lewis’ words in The Last Battle, “I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now...Come further up, come further in!” |

Mike Clifford is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham. His research interests are in combustion, biomass briquetting, cookstove design and other appropriate technologies. He has published over 80 refereed conference and journal publications and has contributed chapters to books on composites processing and on appropriate and sustainable technologies.

In 2009, he was voted "engineering lecturer of the year" by the Higher Education Academy's Engineering Subject Centre for his innovative teaching methods involving costume, drama, poetry and storytelling. |