When God & Science Hide Reality

By Davis Woodworth

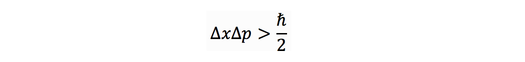

In both science and faith, truth can take on perplexing forms. In 1665, the British scientist Robert Hooke published a seminal work of scientific observations and beautiful illustrations: Micrographia.[cr1] Hooke used the newly-invented technology of the microscope to take a peek at everyday objects with a clarity that was previously impossible to attain. Part scientific report, part leisure guide for the wealthy British gentleman, Micrographia provided instruction on how to look into the mysteries of the microscopic world. For Hooke, the instrument of the microscope revealed a new beautiful and unforeseen place, enabling humans to see the world through a divine lens, that is, to see a part of our world a little closer to how God sees it. In the centuries following Hooke’s Micrographia, scientists have gone beyond telescopes and microscopes to explore and measure the cosmos. We have mapped the “cosmic background radiation,” or a kind of scarring in deep space-time left by the Big Bang. We have harnessed the magnetic spin of protons on water molecules to visualize the function and anatomy of the human brain. We have built twin two-and-a-half-mile-long perpendicular light-interferometers that require the precision to detect a change in length of less than the width of a proton to listen to the waxing and waning of space itself as gravitational waves course through it. Scientific instruments and scientific paradigms allow us to see things that were previously hidden. It is in this sense that we can say science begets aletheia, or truth: it uncovers previously unknown reality to us. However, as our scientific instruments have increased in power, they seem to reveal as much mystery as they reveal so-called “naked truth.” Such is the case in the strange world of quantum mechanics. The Strangeness of Quantum Mechanics Quantum mechanics is an odd duck in the modern collection of natural sciences. While scientific discovery into the early 20th century seemed to be producing ever more precise theories and measurements, things started to take a different turn in quantum mechanics. The famous “uncertainty principle” is a classic example. First developed by Werner Heisenberg, a German physicist and crucial architect of quantum mechanical theory, according to the uncertainty principle, the position and velocity of a particle cannot be known precisely at the same time, so there is always uncertainty in the measurements performed. The uncertainty principle takes on the simple form of the equation: Where Δx is the uncertainty in the measurement of the position of a particle, Δp is the uncertainty in the measurement of the momentum (mass multiplied by velocity) of a particle, and ℏ is the reduced Planck constant (a very small measure of energy). In other words, the uncertainty in the measurement of position multiplied by the uncertainty in the measurement of the momentum of a particle is always greater than a certain amount of energy. We can never know both the exact position and the exact momentum of a particle simultaneously, and the more precisely we know one, the more uncertain our estimate is of the other. Granted, the scales at which the uncertainty principle begins to play a noticeable role in the interactions between particles are indeed extremely tiny, so these uncertainties are completely unnoticeable in everyday life. But this is not some mistake by the scientist, a mishandling of the instrument or contamination of the measurement—this is an inherent property of the universe, a veil of uncertainty laid on the fabric of reality. As far as we can tell, the most basic structure of our universe is concealed from the view of science. We may be tempted to knock science down a peg due to this seeming blunder of quantum mechanics, that science has in some way hidden truth from us. But science is not alone in this conundrum of strange truth: what do we, as Christians, make of Jesus, the Christ, who is the full revelation of God, and yet shrouded in such immense mystery? The Strangeness of Christ Karl Barth, the influential Swiss Reformed Theologian, said of the revelation of God: “God can be called the truth only when ‘truth’ is understood in the sense of the Greek word aletheia. God's being, or truth, is the event of his self-disclosure.” In other words, God must reveal God’s self to become known. Only in the event of God’s self-disclosure can God be called aletheia because God is not bound by other truths. In the gospel of John, Jesus says: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life.” Christ is the aletheia, the “unconcealedness” or revelation of God. However, in this very same self-revelation of God, Barth also sees a concealing of God’s own self in the incarnation. God is revealed to us through the incarnation, but God also conceals God’s self by appearing in human form, a creature within creation. God is known through the patterns we see in human history stemming from the cultural and spiritual interventions of Jesus Christ, and yet Christ by being embedded in history, in a particular time and space, is also hidden from us. Thus in Christ, we have the unveiling of God, but we also have a stumbling block: God hidden in the veil of flesh. In his Church Dogmatics, Barth states that the starting point for understanding God’s attributes is the self-revelation of God in this fully veiled and fully unveiled presence among us. We are ever dependent on God’s grace for revelation, because we can never fully apprehend God, but we can know God through faith in Jesus Christ. And so, This is the great truth the church must proclaim, which can be difficult to do at times. This is a truth that we cannot derive, a truth that is not self-evident. So, while we proclaim the truth, the revelation of God, the aletheia, that is Jesus Christ, this truth is forever strange to us, forever out of our control, only possible through the grace of the unveiled/veiled God. Strange Bedfellows? Science has enabled us to understand vast swaths of the universe we inhabit. We can share in Hooke’s admiration of the world by accepting the truths brought about by science as coming from God. Karl Barth agreed that we should strive to understand reality in scientific terms, the universe being a gift from God that should be examined and studied, going so far as to say that we disobey God when we try to distort facts presented to us by science. But science is not absolute in its truth-telling, (as with the uncertainty principle, it sometimes introduces as many complications as it eliminates). Yet we as Christians are also at a sort of impasse with respect to our knowledge of the truth that is Christ, for he is both the concealment and unconcealment of God to us. To know Christ requires faith. Perhaps Christians and scientists can find common ground in our respective commitments to aletheia, truth, strange and particular as those truths can be, by recognizing that the truth each believes in is at the same time an uncovering and covering of hidden things. Someone who was able to recognize both the strange truth of quantum mechanics and the strange truth of Christ was Werner Heisenberg. Not only was Heisenberg a Nobel-winning physicist whose work revolutionized the way we see our universe, he was also a committed believer, described by contemporary physicist Henry Margenau as “... a true Christian in every way.” In a lecture entitled Scientific Truth and Religious Truth, Heisenberg talked about the incredible advancements in knowledge brought about by science, that the truths of science are unassailable in their own sphere. But besides these scientific facts, there also exists a reality, a “spiritual form”, religion that guides the ethics, trust, and artistic life of the community. Of religion, Heisenberg said: “Only here do we see the close relationship between the good, the beautiful and the true; only here can we talk of a sense for the life of the individual.” For us as Christians, this sense of life, this relationship between the good, the beautiful, and the true (strange as the “true” may be), happens in Christ and in his Church. And this strange truth creates a space where we can marvel at, interact with, and appreciate the truth of science, strange as it may be as well. |

Davis Woodworth is a PhD candidate nearing completion at the Physics and Biology in Medicine Interdepartmental Program at the University of California, Los Angeles, where his research focuses on leveraging advanced MRI scans to probe the structure and function of the central nervous system in various neuropathologies. Prior to graduate school Davis earned his B.S. in Physics from the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Davis grew up as a missionary kid (MK) in Colombia, during which time he developed a deep love for science while reading and re-reading Paul Hewitt’s “Conceptual Physics” textbook. And then, while studying physics in undergraduate and graduate school, he developed a deep love for biblical studies and theology… go figure! Davis lives, studies, and commutes, in Southern California, alongside his lovely wife, Rebecca. |