God and Nature Winter 2019

A Column by Mike Clifford

"An Academic Marriage of History and Engineering"

by Mike Clifford

Regular readers will know that I’m an enthusiast of the multi-disciplinary approach to problem-solving. During my time at the University of Nottingham, I’ve held academic posts in three of its five Faculties (Engineering, Science and Social Sciences), and I’m currently co-supervising a postgraduate in the Faculty of Medicine. That left the Arts Faculty (which includes the History Department) an unexplored paradise for me – until very recently. (As an aside, when people see “Faculty of Engineering” on my name badge at conferences and ask me if I’m really an Engineer, I tell them that if I slept in the garage, it wouldn’t turn me into a motor car. But I digress.)

My recent foray into the Arts started with a chance conversation about educational reform and Beatrix Potter, which put me in contact with a historian whose thesis revolves around the involvement of the University’s staff and students in The Great War. Back in those days, the University had yet to receive a royal charter and was known as University College Nottingham.

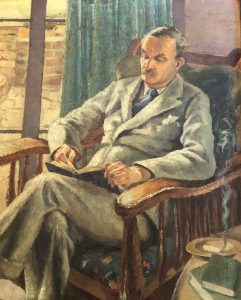

Under the leadership of Professor Charles Bulleid, the Engineering Department made extensive contributions to the war effort, turning its workshops and laboratories over to private companies engaged on His Majesty’s Service. Much of what went on wasn’t recorded, so I’ve been trying to assist the historians to match Prof Bulleid’s engineering expertise with his wartime activities.

The name “Bulleid” is often linked to steam engines. After graduating with a 1st from Cambridge, Charles served an engineering apprenticeship in the locomotive department of the Midland Railway in Derby before becoming Assistant Technical Manager at Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company in Newcastle. Once he moved to University College Nottingham, he went on to take an interest in materials testing and formed links between the University and many engineering companies including Rolls Royce – a partnership which continues to this day.

Regular readers will know that I’m an enthusiast of the multi-disciplinary approach to problem-solving. During my time at the University of Nottingham, I’ve held academic posts in three of its five Faculties (Engineering, Science and Social Sciences), and I’m currently co-supervising a postgraduate in the Faculty of Medicine. That left the Arts Faculty (which includes the History Department) an unexplored paradise for me – until very recently. (As an aside, when people see “Faculty of Engineering” on my name badge at conferences and ask me if I’m really an Engineer, I tell them that if I slept in the garage, it wouldn’t turn me into a motor car. But I digress.)

My recent foray into the Arts started with a chance conversation about educational reform and Beatrix Potter, which put me in contact with a historian whose thesis revolves around the involvement of the University’s staff and students in The Great War. Back in those days, the University had yet to receive a royal charter and was known as University College Nottingham.

Under the leadership of Professor Charles Bulleid, the Engineering Department made extensive contributions to the war effort, turning its workshops and laboratories over to private companies engaged on His Majesty’s Service. Much of what went on wasn’t recorded, so I’ve been trying to assist the historians to match Prof Bulleid’s engineering expertise with his wartime activities.

The name “Bulleid” is often linked to steam engines. After graduating with a 1st from Cambridge, Charles served an engineering apprenticeship in the locomotive department of the Midland Railway in Derby before becoming Assistant Technical Manager at Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company in Newcastle. Once he moved to University College Nottingham, he went on to take an interest in materials testing and formed links between the University and many engineering companies including Rolls Royce – a partnership which continues to this day.

Bulleid’s expertise was considered so essential that he was appointed General Manager of the National Projectile Factory. Although this would have been highly demanding work, he remained in post as professor, being granted special leave, with the condition that he continued to ‘undertake the general responsibility of the Department and conduct classes one morning and one evening per week’. The National Projectile Factory was a very dangerous place to work, and indeed a similar factory just a few miles away suffered a large explosion towards the end of the war with the loss of 134 workers, mostly women.

The following year Bulleid assumed the role of Chief Engineer of the Admiralty School of Mines at HMS Gunwharf in Portsmouth, which was responsible for developing and maintaining naval mines and torpedoes (as well as for devising countermeasures against enemy use of the same). While he do not know the nature of Bulleid’s work for the Admiralty, perhaps he drew from his experience with Parsons.

My research into Charles Bulleid took on a personal note when I realised that I had some of his lecture slides in my possession, having rescued them from being thrown away twenty years ago. The glass slides contain drawings of various steam engines and are accompanied by his hand-written notes. I also managed to make contact with Charles Bulleid’s granddaughter, Liz Gross, who filled in personal details about her grandfather. In addition, I visited two houses where he lived, finding that one was now occupied by a Nottingham graduate, who was intrigued to hear about the house’s previous occupant.

Bulleid left a strong impression on his students, with one fondly recalling his university years in the early 1940s, describing him as a “shabbily-dressed, chain-smoker of Woodbines and a beloved eccentric with a mercurial mind”. “All his lectures were virtuoso performances and extempore, such that all the students felt they were sharing an adventure for the first time” (1).

The following year Bulleid assumed the role of Chief Engineer of the Admiralty School of Mines at HMS Gunwharf in Portsmouth, which was responsible for developing and maintaining naval mines and torpedoes (as well as for devising countermeasures against enemy use of the same). While he do not know the nature of Bulleid’s work for the Admiralty, perhaps he drew from his experience with Parsons.

My research into Charles Bulleid took on a personal note when I realised that I had some of his lecture slides in my possession, having rescued them from being thrown away twenty years ago. The glass slides contain drawings of various steam engines and are accompanied by his hand-written notes. I also managed to make contact with Charles Bulleid’s granddaughter, Liz Gross, who filled in personal details about her grandfather. In addition, I visited two houses where he lived, finding that one was now occupied by a Nottingham graduate, who was intrigued to hear about the house’s previous occupant.

Bulleid left a strong impression on his students, with one fondly recalling his university years in the early 1940s, describing him as a “shabbily-dressed, chain-smoker of Woodbines and a beloved eccentric with a mercurial mind”. “All his lectures were virtuoso performances and extempore, such that all the students felt they were sharing an adventure for the first time” (1).

During all of this detective work, I kept asking myself what part I might have played had I been an academic during the war years. There were many other contributions that the university’s staff made to the war effort – as front-line troops, fighter pilots, and medics – and there were of course also conscientious objectors who refused to have anything to do with fighting. Over one hundred years after the end of the Great War, it’s hard to see what the point of all the bloodshed was, much harder than in the case of World War II (though even there we need the advantage of hindsight). More recent conflicts seem to have only increased the sense of danger both at home and overseas. The Great War, the war to end all wars, certainly didn’t achieve that aim, and it’s hard to think of any conflict that has secured a lasting peace.

Special thanks to Liz Gross (granddaughter of Charles Bulleid) and Mike Noble, from the Department of History at the University of Nottingham for their content contributions and the images included in this item.

(1) Lowry, Emma. Nottingham in the War – “Beloved” Bulleid: the Nottingham engineer helping the war effort. University of Nottingham blog.

Mike Clifford is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham. His research interests are in combustion, biomass briquetting, cookstove design and other appropriate technologies. He has published over 80 refereed conference and journal publications and has contributed chapters to books on composites processing and on appropriate and sustainable technologies.

Special thanks to Liz Gross (granddaughter of Charles Bulleid) and Mike Noble, from the Department of History at the University of Nottingham for their content contributions and the images included in this item.

(1) Lowry, Emma. Nottingham in the War – “Beloved” Bulleid: the Nottingham engineer helping the war effort. University of Nottingham blog.

Mike Clifford is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham. His research interests are in combustion, biomass briquetting, cookstove design and other appropriate technologies. He has published over 80 refereed conference and journal publications and has contributed chapters to books on composites processing and on appropriate and sustainable technologies.