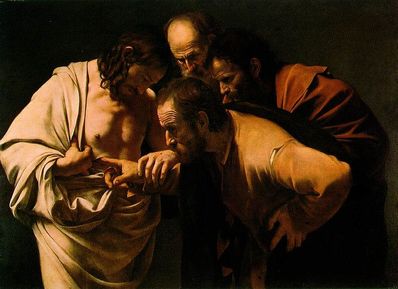

Proofiness Caravaggio's "The Incredulity of St. Thomas"

It’s morning, a few weeks after Easter, and spring has come to the Ohio River Valley. The cherry and dogwood are festooned in shivering clouds of white and pink. The daffodils tower over the violets, and the violets stare up at them in purpled awe. The robins are hopping around fatter than ever, their beaks full of muddy, wriggling prey. All these things, bright and beautiful, are good to see. They fill my heart with joy, and I accept the fact of this joy without questioning.

So why can’t I get poor Thomas out of my head? We’ve all heard the story of the doubting disciple; most of us hear it every year at Easter time: Now Thomas (also known as Didymus), one of the Twelve, was not with the disciples when Jesus came. So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord!” But he said to them, “Unless I see the nail marks in his hands and put my finger where the nails were, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe.” Now that may seem awfully pessimistic on Thomas’s part. But who knows what was running through the frightened disciple’s mind when he heard Jesus had risen from the dead? The man who visited the Twelve could have been an imposter, a practical joker, a spy. I, too, would probably have requested proof. Fortunately, Thomas receives what he asks for: A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe.” Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!” Then Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” A week earlier, when Jesus had come to visit the Twelve who were huddled in a locked room, he had offered his hands and side to them without hesitation—even before they had made the request. He then ate a piece of broiled fish in front of them. Their eyes were opened, and they rejoiced. Jesus didn’t have to be omniscient to know his resurrection from the dead wasn’t going to be easy to believe. Proof was necessary in those first meetings—right? If you think about it, Thomas reacted like any good scientist. He refused to let his mind be led astray by his emotions. He sought verification. He observed carefully. He drew conclusions from the evidence in front of him. Only then did he let himself succumb to the joy the others had already experienced. So why is Thomas gently admonished for his doubt? “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.” For me, these are some of the most simultaneously challenging and encouraging words Jesus ever spoke. I repeat this phrase in the “locked room” moments of my own life—when I am in hostile company, or very dark hours, questioning the foundations of my faith. It happens more than I care to admit. I wish I were a bit less like Thomas. Never again in human history—that we know of—has a disciple of Christ had the opportunity to physically affirm his or her faith in Jesus’s resurrection. That must have been an unimaginable privilege—and yet, I do think it’s possible that Thomas would have come to believe, like every living Christian today, even if Jesus had not shown himself to Thomas. He just would have had to grapple with a different kind of evidence: authority. While Thomas hadn’t been in the room when Jesus first appeared, he’d heard from the mouths of all the remaining disciples that they had, in fact, seen their teacher. Alive. Scars and all. Were these men, along with Mary Magdalene and the other Mary, reliable enough to trust with such mind-blowing information? Should the word of the Twelve have been sufficient? “Blessed are those who have not seen, yet have come to believe.” Christians today wrestle with authority from top to bottom. For many, the Bible is the ultimate authority on everything—from how we should behave toward others to why we still grow wisdom teeth. Others take authority from a mindful combination of God’s “two books”: the book of Scripture and the book of Nature. The former contains the wisdom, poetry, and history on which we base our Christian identity. The latter contains evidence of all God has written before and since: the beautiful code that rose from molecules jostling about in the primordial pools, the deep history of time on earth and in the universe, even clues as to why we experience awe at the sight of a brilliant, red-and-purple sunset or a rainbow after the rain. While there’s a good deal of evidence out there to support the belief that Jesus lived and moved and changed the course of human history, there’s no shrine we can visit to thrust our fingers into the man’s weeping hands and gaping side to affirm that there was anything miraculous about his existence. I have read a lot of articles recently that grapple with the question of whether we need proof of God, or heaven, or that Jesus really rose from the dead and ate broiled fish on that first Easter Sunday. A few of these articles ask the question, “Can a true scientist really believe in God?” All scientists are professional skeptics. In the lab, they take nothing on faith alone (unless you consider the blind intuition, to cast out in a new direction of inquiry, a kind of faith). But there are many things that even the best of scientists must accept on the authority of those who have come before them asking questions and making observations. How many have gone outside with a telescope and slide rule to prove the earth is not the center of the universe? How many have traveled far enough into the stratosphere that they can reliably report that there is, in fact, no hard dome encasing our planet and holding the celestial waters at bay? Yet there’s no doubt in most people’s minds that the calculations and observations involved in coming to these conclusions were performed with integrity, were reliably tested and retested, and that (for now, at least) they are correct. I want to say one thing about “proof” when it comes to science and Christianity. Scientists who believe in God do not need hard physical evidence that God exists. There is no calculation, no path of logic, which can formally secure their faith against the doubt and the aspersions of others. For scientists who believe in God, the authority of those who have come before them is an acceptable form of evidence for the miracle of Christ’s resurrection, the central tenet of the Christian faith. Many will tell them that that is not sufficient proof. They are, in a way, correct. That is where faith comes in. And unless one has experienced the joys of humbly submitting oneself to faith, it may hard to discern what good can come from suspending that safeguarding disbelief. Truly, “Blessed are those who have not seen, yet have come to believe.” —Emily Ruppel |