My Overlapping Magisteria Spectators at the Greenbelt Festival. Photo: Jonathon Watkins (2007)

By Tim Middleton

“Are your magisteria overlapping?” asked Robin Ince, a British comedian and an atheist. I quickly checked. They seem to be at the moment, I thought. “In fact,” he continued, “who here even understands the question?” I was sitting in about two inches of mud, sheltering under a large awning at Greenbelt festival; the event was a discussion between Ince and the Reverend Richard Coles about science and religion, and Ince’s question referred to Stephen Jay Gould’s idea that these two magisteria—or domains of teaching—should be subjected to “principled and respectful separation.” [i] For Gould, also an atheist, faith deals with questions of ultimate meaning and moral value, while science is concerned with demonstrated truths and observed facts. Gould called his idea the principle of non-overlapping magisteria, or NOMA. Ince and Coles had an interesting discussion, but by the end I felt they had missed something. The tacit assumption was that any overlap was a bad thing—science and religion should be kept in separate corners of the tent to avoid any unnecessary bloodshed. But what if they could overlap in a good way, I thought? Before we get to that, though, we must recognize that Gould makes two important points in his elaboration of NOMA. First, science cannot be the basis for value judgments. As Gould puts it, “The facts of nature cannot determine the moral basis of utility.” [ii] Theoretical physicist Steven Weinberg explains what he means: “Endless trouble has been produced throughout history by the effort to draw moral or cultural lessons from discoveries of science.” [iii] For example, Aristotle had a way of thinking about the world that was based on a concept of ‘naturalness’—but this was often extrapolated to the worrying notion that some people are ‘naturally’ slaves. If we’re going to learn from our historical mistakes, then it probably isn’t a wise move to be investing time forcing God into currently unintelligible spaces.

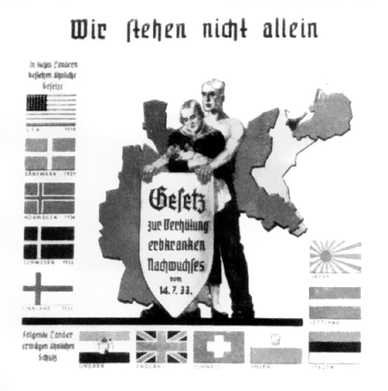

Nazi "compulsory sterilization" propaganda

Similarly, the Darwinian theory of evolution by natural selection was used to justify the atrocities of Nazi Germany. In fact, rather alarmingly, some sort of eugenic thinking—the idea that it is possible to self-direct human evolution—was at one time highly regarded by people such as Winston Churchill, Theodore Roosevelt and John Maynard Keynes. It was understandable, following the publication of Darwin’s ideas, that people would start thinking with science, but this example shows just how easy it is to fall into the trap of letting science, alone, dictate your actions. External moral codes can be used to interpret scientific facts, but no conclusion is necessarily implicit in the science itself.

Gould’s second point is that religion, too, should not overstep its remit, not least because it will only serve to be its own undoing. There is a wise adage that says, “The theology that marries itself to the science of today will find itself the widow of tomorrow.” A prime example is the renewed desire for a ‘natural theology’ that developed in the early nineteenth century in the wake of the scientific revolution. Religious believers, aware of the new science’s attempt at rationality and objectivity, wanted ‘proofs’ for the existence of God. The ontological, cosmological and design arguments, made famous by the likes of Paley’s watch, took on a new popularity. But today, many Christians would agree that it simply isn’t possible to produce watertight, deductive proofs for the existence of God. Rather, any attempt to do so is systematically dismantled by the New Atheists and used to ‘disprove’ religion. Another good example is the modern interest in quantum indeterminacy and chaos theory as ways in which divine intervention could be accommodated ‘scientifically.’ However, as Arthur Peacocke points out, to make such a claim is to suggest a “God of the uncloseable [to us] gaps.”[iv] In due course, science may or may not have more to say about these topics. If we’re going to learn from our historical mistakes, then it probably isn’t a wise move to be investing time forcing God into currently unintelligible spaces. A third and final example of religion overstepping its remit can be found in the so-called ethnosciences. This is where science is co-opted by a pre-existing culture, and scientific rationality is subordinated to the ‘forms of life’ of a certain community. Noble visions of an ‘Islamic science’ have been hijacked by I’jaz, the attempt to find miraculous scientific content within the Qur’an. Using a Qur’anic verse to try to calculate the speed of light is both absurd and unhelpful. Similarly, ‘Hindu science’ was lead astray by fundamentalists who made the study of ‘Vedic mathematics’ compulsory in many Indian schools. Algebra and calculus were replaced by a set of sixteen Sanskrit verses in an attempt to pass off a set of clever formulas as a piece of ancient wisdom. Within evangelical Christian cultures, ‘creation science’ is another example of a kind of ethnoscience: a pseudo-scientific attempt to try and provide support for a literalist reading of the Genesis creation narrative. So what are we left with? We have seen numerous examples of unhealthy ways for science and religion to overlap. So why are my magisteria still overlapping? One really important consideration is that ‘science’ and ‘religion’ are not fixed categories. This is the mistake often made by the media: journalists, motivated by the scent of conflict, have often portrayed a polarized debate, missing the complexities of the relationship. True, certain religious beliefs are inconsistent with certain scientific observations; radioisotope dating suggests that the earth is four and a half billion, not ten thousand, years old. But other faith positions are perfectly compatible with science. As the historian Thomas Dixon puts it, “Science and religion are both hazy categories with blurry boundaries, and different sciences and different religions have clearly related to each other in different ways.”[v] So perhaps there is hope for a fertile form of overlap. For me, the reason that science and religion can’t be banished to separate rooms in the way that Gould would like is that religious faith is something that permeates all aspects of my life. Gould tries to be respectful of religion in the way that he places it alongside science as a legitimate field of inquiry, albeit one he doesn’t subscribe to himself. But faith, to use Gould’s analogy, isn’t just another painting in the gallery of your mind. Placing God in an ornate frame in the corner, which some people choose to look at and others don’t, is to misconstrue what religion is about. For those with faith, there would be no paintings, no galleries, and no mind if it weren’t for God; God is the reason there is something rather than nothing. As a Christian and a scientist, I study a world which I believe God made and continues to sustain. John Polkinghorne describes it perfectly: “God renders the intelligibility of the Universe itself intelligible.” [vi] I think it’s safe to say my magisteria are definitely overlapping. References: [i] S. J. Gould, Rocks of Ages – Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life (2001), p. 4. [ii] S. J. Gould, Rocks of Ages – Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life (2001), p. 94. [iii] As quoted in: Lingua Franca Editors (ed.), The Sokal Hoax – The Sham That Shook the Academy (2000), p. 167. [iv] As quoted in: N. Guessoum, Islam’s Quantum Question – Reconciling Muslim Tradition and Modern Science (2011), p. 338. [v] T. Dixon, A Very Short Introduction to Science and Religion (2008), p. 15. [vi] J. Polkinghorne, The Science and Religion Debate – An Introduction, Faraday Paper No 1. (2007), p. 2. |