A Walk Within Two Worlds: Faith, Science, and Evolution Advocacyby Amanda Glaze

Beliefs are part of the framework that makes us who we are as individuals, and determine how we fit who we are into the larger society in which we live. Our experiences, upbringing, education, culture, beliefs, and other interactions create for us a worldview – the lens through which we view and evaluate all other experiences and information. Where there is alignment, the worldview grows, but where there is conflict, worldviews can serve as a barrier to understanding, acceptance, and growth. Through my research and concurrent public outreach with evolution education, I have learned a great deal about the roles and power of beliefs, worldviews, faith, and evidence in our everyday experiences. I have also learned a great many personal lessons about holding firm to my faith while studying what many view as one of the most controversial concepts in all of science, and about how I can be a voice that bridges the gap between faith and science for people who share these experiences.

Growing up in the rural South, my background was deeply rooted in my church family as much as my nuclear family. My father, uncles, and grandfathers were involved at various levels in ministry – one side Methodist, the other Southern Baptist – so much of what I did growing up was connected to the church. I find, especially in the South, that this is a common experience many share, as so many of our events are hosted by or supported by our churches. My love of all things science entered my worldview very early through a combination of experiences, and the support I had to push the boundaries of my understanding laid a foundation for me to take my curiosity to the highest levels. Both my faith and my love of science were deeply challenged in my high school and college years, yet I have come through these experiences with a renewed passion for both.

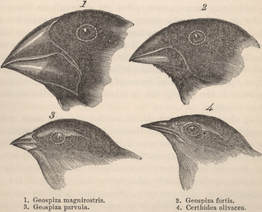

In my culture and community, the word evolution was taboo, something to be feared and avoided, with the penalty being eternal death. While that sounds extreme to those on the outside, as an evangelical protestant Christian, not only was I reared in a literalist creationist denomination but tasked with not only watching out for my own soul but the souls of all others with whom I would have contact. I remember distinctly my grandmother telling me that my work, my research, and what was born of it were a part of my testimony and that she was so afraid that she would not see me in heaven because I “believed in” evolution. Allow me to state this here: I do not believe in evolution. This statement has earned me a bit of notoriety, but please allow me to elaborate. I do not believe in evolution, because evolution is not a matter of faith; it is a process that occurs whether I believe in it or not. Rather, I accept evolution as the best possible scientific explanation for the diversity and unity of life on this planet, and I do so based on evidence supporting evolution. My faith is reserved for my beliefs, particularly my belief in God and His promise for those who follow Him. I can, and I do, love both science and God. The idea that we must choose one or the other is a false dichotomy. What is necessary, however, is an understanding of both science and religion as distinct from each other, a sort of “cognitive apartheid,” if you will. As a scientist, I see science as the explanation of events in nature based on physical evidence that is falsifiable, self-correcting, and measurable. I have had many conversations with people around the country who feel that science exists to try and show that God is not real. What many don’t understand is that the basic premise of science is that God (or any other metaphysical/supernatural entity) cannot be considered as a scientific explanation, as there is no way to scientifically “test for” the presence of God. As a Christian, I see God in the beauty of the world around me, in the interconnectedness of all life (as demonstrated in evolution), and through the ever-complex nature of the universe. My acceptance of evolution is based on empirical evidence. My relationship with God, however, is steeped in my faith, which comes from my upbringing but also has connections the small-ness and wonder that I experience daily through my growing understanding of the world around me. It is common for misconceptions about missing links, theories, conspiracies, and controversy to share space with the mention of evolution, contrary to the consensus of scientists on the matter. As an assistant professor, researcher, and science communicator in evolution education, I have found that it is my own positionality – my background and experiences – that have framed my approach to talking with others about evolution in a way that opens dialog instead of shutting it down. My own experience in adding a scientific worldview to that which I already had in place was a harsh one that I have found is relatable to many. On one side I had family, friends, and others whom I deeply trusted telling me that evolution was essentially evil and something not to be discussed, while on the other side I had people mocking my beliefs and eschewing the very idea of any form of God. Conversations from either extreme pushed me further and further until I began to feel that I belonged to neither. Luckily, I was able to navigate the struggle with my identity (because worldview is very much an identity construct) through reading both in theology and in science and by actively engaging with others until I recrafted my sense of self regarding both. What was missing through my experiences was a mediator, a safe person in the middle ground to help me navigate and balance my desire to question, my love of science, and my fear of hell if I took the wrong path. Discussing the nature of science and setting the “tone” of the interaction provides a key framework for a conversation that can often otherwise be uncomfortable or confrontational, by making clear that learning science is not attacking religion. I have found that in order to be understood and to make your case, you must seek first to understand – you must be willing to listen more than you speak, and to recognize just how deeply rooted worldviews are for individuals. I empathize with the stress that many feel regarding evolution because I have lived it first-hand. After years of talking to my family, friends, and now the public about my research, I have found that there are many more people who fall in the middle (or want to) than those on the extremes, and they are happy to have a voice that reflects their desire to be people of faith and people of science. Our goal in evolution education is not to supplant students’ worldviews, but rather to add a scientific worldview to what they already have, regardless of whether they are believers or not. My grandmother was certainly correct: my voice and my work are very much my personal testimony, and it is a testimony that I am proud to share. I am happy to be an example for others of faith that you can be both scientific and a believer, and an advocate of evidence as well as of faith. |

Amanda Glaze specializes in science teacher education, evolution education research and outreach, and professional development, alternating her time between the classroom and the field as an Assistant Professor of Middle Grades & Secondary Science Education at Georgia Southern University. Her research centers on the intersections of science and society, specifically the acceptance and rejection of evolution in the Southeastern United States and the impact of the conflict between religion and evolution on science literacy. Her work can be found in Science Education, The American Biology Teacher, Education Sciences, the International Journal of Mathematics & Science Education, on NPR's Science Friday Macroscope and various other media outlets.

|