Political Science?

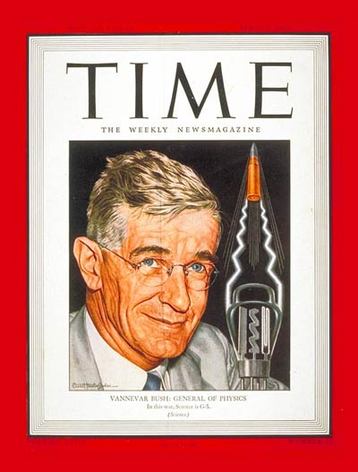

A TIME magazine cover from 1945 features a portrait of Vannevar Bush

By Walt Hearn

The National Science Foundation (NFS) has an annual budget of about $7 billion "to promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare; to secure the national defense..." largely through grants to "principal investigators." Many young scientists supported by NSF may not recognize the name of Vannevar Bush, "patron saint" of NSF and of federal research grants in general. Bush (1890-1974) was an electrical engineer and once dean of engineering at MIT. He helped found Raytheon Company, which gave us the microwave oven, among other things. Raytheon is now the world's largest producer of military guided missiles. By mobilizing American scientists for big projects in WWII, Bush (no relation to G.W.) gained prominence as a policy maker. He led a number of wartime organizations, especially OSRD (Office of Scientific Research and Development). With F.D.R.'s encouragement, Bush argued strongly for federal research grants in a report delivered to President Truman in July 1945. Science, the Endless Frontier touted the role of basic science in national defense and technological progress. In 1950, OSRD more or less morphed into NSF. Vannevar Bush's name came up at the 2012 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in the George Sarton Memorial Lecture, "Making Science Big," given by U. of Alberta historian Robert Smith. (Oops, from that video I learned that I've mispronounced that name all these years: it's "Van-NEE-var," not "VAN-ne-var.") To show that scientists sometimes cultivate a public image that differs from the way science is actually done, the lecturer projected a 1942 photograph of Bush sitting alone at his laboratory bench (or at somebody's bench). The photograph was obviously posed, Smith said, because by that time Bush had already stopped working in the lab to devote himself to promoting "Big Science," such as the Manhattan Project, which gave the world the atom bomb. That set me to thinking about the status of science today and reminded me of an insight I had while writing Being a Christian in Science (IVP, 1997). I was responding to a charge that Christian theology (which "produces nothing," to paraphrase atheist Richard Dawkins) deserves to be eclipsed by science, which has produced not only vast knowledge but also many useful things—such as antibiotics and atom bombs. The idea of promoting science for its potential role in national defense goes back as far as the 17th century, when Galileo pointed out the military and commercial usefulness of his new telescope. In roughly the same number of centuries that it took the church to become an influential cultural establishment deeply entangled with political powers, science has done the same.

American Scientist magazine shows the scale of the LHC

My insight was that for their first few hundred years, Christianity and science had similar histories, with science only now coming out of that initial phase. Here's the parallel as I described it:

"For roughly its first three hundred years, Christianity was essentially a fellowship of joyfully creative yet serious people who surprised the culture around them by their won derment and absorption in 'unworldly' pursuits. The early Christians were often misunderstood and even persecuted as a dangerous counterculture—until Christianity rather suddenly became an established religion. With the conversion of the emperor Constantine in 323 A.D., the church received govern ment recognition, but at the price of entan glement with political establishments. "By about a dozen centuries later the church had become a dominant cultural force in Europe, but an institution thoroughly beholden to secular powers. That was when European science got its start—as essentially a fellowship of joyfully creative yet serious people surprising the culture around them by their wonderment and absorption in another kind of 'unworldly' pursuit." (p. 41) I argued that the transformation of science from that kind of fellowship was more or less inevitable, once scientists sought patronage from wealthy rulers. The idea of promoting science for its potential role in national defense goes back as far as the 17th century, when Galileo pointed out the military and commercial usefulness of his new telescope. In roughly the same number of centuries that it took the church to become an influential cultural establishment deeply entangled with political powers, science has done the same. Scientists may, to ordinary citizens, already resemble the heavy hitters of the medieval church, which in its day was certainly "Big Christianity." Maybe back then one might have heard: "O Noble and Benevolent Sire, it is obvious that the Christian religion unites your subjects and protects your incomparably magnificent realm. Your empire should have state-of-the-art cathedrals, which only Your Exalted Majesty can afford to build. How can your humble servants do world-class, cutting-edge Christianity, or produce religiously literate citizens, without your sustained and generous support? We need grants from something like (may we suggest?) a Neogothic Salvific Foundation." Sound familiar? So far, "the largest scientific instrument ever built" is CERN's Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. In a photograph on the cover of the March-April 2012 issue of American Scientist, one of the two detectors of that huge particle accelerator dwarfed the figure of a hard-hatted workman being lifted on a crane to tinker with it. What next? Science is certainly robust, and—if nobody starts using all those atom bombs—might last as long as Christianity already has. At some "tipping point," though, taxpayers may tire of supporting such a costly enterprise. The Protestant Reformation cut Big Christianity down to size, and many would say that Christianity benefited from that fresh start. Could "Big Science" ever get too big for its britches? Of course, "at heart" science is individual people, not a gigantic institution. At least, we prefer to think of it that way. In posing for his 1942 photograph, Vannevar Bush was trying to convey that impression. Seventy years later, Big Science is much bigger and ever more dependent on government sponsorship. The European debt crisis jeopardized funding for CERN. In April 2012, the 38th Annual AAAS Forum on Science and Technology Policy was downright pessimistic. The deputy director for extramural research at the National Institutes of Health pretty much said that it's time to batten down the hatches. During the 1980s, the success rate of applicants for NIH research grants was 40 percent; in 2012 it's down to 18 percent. It's true that basic research is also funded by philanthropic foundations, and that much R&D (applied research and development) is funded by large corporations. Space Exploration Technologies Corporation ("SpaceX") has sent a cargo payload to the International Space Station for about $1 billion. Some $200 million of that came from private investors, maybe twice that much from down-payments for future space missions, the rest from government contracts (different from research grants). Is a new future for research on the launch pad? The websites of most American scientific societies now have pages on "policy" or "advocacy" about proposed legislation that could affect government support. Early this year, AAAS even launched a website to show researchers which way the wind bloweth. Where it listeth, no doubt. |