Beyond the Pond

The quad of New College, Oxford

by Walt Hearn

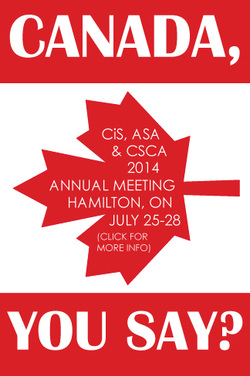

Did you hear the latest news from the 15th century? It seems that in 1485 England's King Richard III was buried crudely in Leicester after dying in the battle of Bosworth Field. In 2012, archeologists from the University of Leicester figured out where to dig for Richard's bones and in early 2013, University geneticists identified the remains. How? By comparing mitochondrial DNA from those bones to that of a living descendant of Richard's sister, Anne of York. What's neat about that is that the U. of Leicester is where, in the 1980s, geneticist Alec Jeffreys (now "Sir Alec") invented DNA fingerprinting. Leicester isn't one of Britain's "ancient universities" (think Oxford, Cambridge, Durham, Edinburgh) but a modern research-oriented one founded in 1921 and chartered in 1957. It posted a fascinating day-by-day account of both the dig and the DNA matching, at http://www.le.ac.uk/richardiii/index.html It's that juxtaposition of ancient and modern in the U.K. that fascinates Americans. The USA didn't even exist before 1789, and Texas, the state I grew up in, didn't become part of it until 1845. Compare that with Oxford's "New College," founded in 1379 but still "New." In Houston, my home town, perfectly good 20th-century buildings that got a little dusty were torn down to build shiny new ones. In London I was once admiring a half-timbered structure that seemed right out of Shakespeare. A Londoner set me straight: "That's not really old, you know. It was built to replace the old one right after the fire." He meant London's Great Fire of 1666, as though it had happened only a few years before. I wondered if the American Revolution was that fresh in English memory. On another stay in London I visited the National Army Museum in Chelsea, with exhibits and artifacts of battles dating back to 1066. I found a small section devoted to "Loss of the American Colonies." Captions implied that it happened because the best of the British army was busy elsewhere. I'd never thought of it that way. Our two countries have a lot in common, including rather similar languages. Once on a sidewalk outside my London lodgings, I was vigorously approached by the driver of a goods lorry ("delivery truck," to Americans), spewing what I assumed to be a working-class version of the native language. I couldn't understand a word, even when he repeated it more slowly but with rising annoyance. He kept coming toward me. The Houses of Tudor and York had settled things with swords. Was this guy challenging me to a duel? As I prepared to parry his thrust I realized that he'd been asking to borrow the ballpoint pen clipped to my shirt pocket. He needed it "fa ‘rony arf’a mo, guv." On the other hand, English spoken by well-bred Brits is so "classy" that Americans like me stand in awe (as in "Aw, shucks"). In 1965 I participated in an international conference held at Regent's Park College, a Baptist "Permanent Private Hall" of the U. of Oxford. I learned a lot, not only about "A Christian Philosophy of Science" (the conference theme), but also about scientifically-trained fellow Christians from around the world. The anonymous donor behind the conference was rumored to be Canadian engineer Norman Lea. Norm must have participated as a representative of ASA (American Scientific Affiliation), since the offshoot CSCA (Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation) wasn't set up until 1973. A third of the nearly 40 conferees were invited from ASA and another third from the British RSCF (Research Scientists' Christian Fellowship), now CiS (Christians in Science). The rest came from various countries, especially the Netherlands. The ASA participants, mostly young faculty members, were impressed by the spiritual and intellectual maturity of colleagues from other countries who had been at the game for years. To them, the Americans must have seemed like adolescents. The most senior participant was science historian R. Hooykas (pronounced HOY-kas) from the Free University of Amsterdam. I had read several of his pamphlets (e.g., Christian Faith and the Freedom of Science, 1957) published by RSCF. At the conference he was always referred to as "Professor Hooykas," either out of respect or because people weren't sure how to pronounce his first name (Reijer). I was told that Prof. Hooykas regarded the Americans as "frivolous." I better understood his serious approach to life when I learned that he had spent weeks hiding between joists under floor boards to avoid arrest during the Nazi occupation of Holland. It probably didn't help his opinion of the American participants when a story went around that some of them had gone out at night to explore Oxford and returned to find the lights out and the college locked down. (In my embellished memory we had to scale the college wall, but maybe we only raised enough ruckus to wake the porter, who rather grudgingly opened the portal for us.) Oxford displayed many evidences of England's rampant "churchiness." Besides the ubiquitous old churches, a lot of other things were named for saints. As I recall, Regents' Park College lay between St. Giles' Road and St. John Street. I even encountered a traffic barricade with the sign, "St. Repairs." And then there were those inter-collegiate sports headlines like "JESUS TROUNCES TRINITY." Seriously, ASA and RSCF discovered how much alike we were, despite some distinctives. Geography made a big difference. ASA members were scattered over vast distances compared to the U.K. At the time most RSCF members were in a few important centers (OK, "centres") close enough together to make meetings easier. Further, unlike ASA, they didn't spend time at those meetings listening to contributed papers with hardly any time left for discussion. No, the Cambridge Group, say, would work on a topic for a year, hammer out a paper, and send it to the other groups weeks before a national meeting. Then the entire meeting could be devoted to in-depth discussion of that one issue. What ASA had going for it was our own Journal (renamed Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith in 1987), publishing scholarly papers for the benefit of a scattered membership. In contrast, RSCF had only a few pages at the end of The Christian Graduate magazine along with those of other alumni professional groups from the UCCF (Universities and Colleges Christian Fellowship), from which Canada's IVF and the USA's IVCF had sprung. Biologist Oliver Barclay was long-time Director of UCCF and also Secretary of RSCF. So, although ASA's existence remained a well-kept secret among college-educated evangelicals in North America, essentially all alumni of the evangelical Christian Unions in British universities knew about RSCF. Shared goals, different approaches, one Lord. Two decades later, after a 1985 joint meeting of ASA and RCSF at St. Catherine's College in Oxford, two busloads of ASAers became more familiar with the U.K. We explored cities in England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, with beautiful countryside in between. On our way to Edinburgh by way of York, I think we may have passed through Leicester, where Richard III's bones were lying beneath a car park ("parking lot" to Americans). Or was that Lester we passed through? I recall an old saw about sauce: What's "Worcestershire" for a (British) goose is "Wooster" for a (Yankee) gander. In July 2014, Canadians will host a meeting of all three societies (CSCA, ASA, and CiS) at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. When Christians trained in science get together, we share common languages of science and robust biblical faith. We agree wholeheartedly with the words of the Baptist hymn writer John Fawcett, born in 1740 at Lidget Green, near Bradford in Yorkshire: Blest be the tie that binds Our hearts in Christian love; The fellowship of kindred minds Is like to that above. Before our Father’s throne We pour our ardent prayers; Our fears, our hopes, our aims are one Our comforts and our cares. We share each other’s woes, Our mutual burdens bear; And often for each other flows The sympathizing tear. When we asunder part, It gives us inward pain; But we shall still be joined in heart, And hope to meet again. This glorious hope revives Our courage by the way; While each in expectation lives, And longs to see the day. From sorrow, toil and pain, And sin, we shall be free, And perfect love and friendship reign Through all eternity. |