In Search of Wonder: A Reflection on Reconciling Medieval and Modern CosmologYBy Monica Bennett

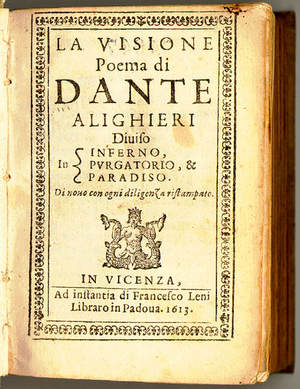

In one of my college literature classes, we spent a large part of the semester reading Dante’s Divine Comedy, suffering through the journey deep into Hell and soldiering up the steep climb of Purgatory. At last, we reached Paradiso, in which Dante as narrator and protagonist bounces from one planet to another, encountering increasing perfection as he moves through the celestial spheres.

Inferno and Purgatorio both contain their share of physical impossibilities, but to the modern reader, Paradiso offers by far the most glaring departure from reality. However, Dante’s poetic descriptions aligned with the astronomical views of his day, inherited from the likes of Ptolemy and Aristotle. Earth was central, with the sun, moon, and the five planets known at that time orbiting in concentric spheres. Beyond these was the sphere of the fixed stars, then the Primum Mobile (Prime Mover), a sphere powered by God that, appropriately, caused the motion of the inner spheres. Beyond all was God’s own realm, the Empyrean, which crowned and bounded the series of shells. The heavenly spheres are fascinating to me for many reasons, one being Dante’s commentary on the spatial nature of creation’s relative proximity to God. Inferno links the literal descent toward the center of the earth to an increasing spiritual distance from God, until the poet and reader encounter Satan himself at the very core of the planet. Conversely, as Dante ascends, he moves steadily into regions of ever-greater holiness, first through the souls laboring in Purgatory and then up into the heavenly realms. In a sense, the physical layout of the cosmos is inverted, with the spiritual core of God’s transcendent Empyrean encompassing everything else. This depiction of God presiding supreme in the heavens points to another essential characteristic of Dante’s medieval universe—the implicit faith in an ordered, rational universe and Creator. Our modern minds, familiar as they are with Enlightenment “watchmaker” metaphors for divine order, might be surprised by the liveliness of medieval ideas about God’s rational nature. Far from moving “programmatically” around their spheres, planets and stars were engaged in an eternal act of worship and love for God. For medieval theologians and penitents, it was this pure joy imbued by God in the universe that gave rise to the music of the spheres. Today, this vision of pristine-yet-animate order, in which even the most lifeless parts of creation are endowed with personalities and voices to praise their Creator, seems best suited to the poetry of the Psalms or wildly imaginative authors like Madeleine L’Engle; that is, it seems out of place alongside modern secular ideas about the structure of the cosmos. Geocentrism, fixed stars, and circular orbits have all been displaced by modern astronomy and cosmology, and that’s not even addressing the problem of a static universe. In Dante’s day, most Christian scholars believed that the whole universe, including the planets, had been created in its present form, impervious to the decay that haunted the sinful creatures of Earth. The “Big Bang” may sound to many modern Christians very much like “Let there be light!”—however, to medieval theologians, it would have represented a challenge to their entire philosophy of creation. The last century or two of science has completely changed our picture of Earth’s—and humanity’s—place in the universe. Since Dante’s time, we had already accepted the diminishment of the Earth to a solar satellite, which was a staggering blow to the idea of human exceptionalism. This demotion was followed within a few short centuries by even more humbling news: not only was Earth not the center of the universe, it didn’t even orbit the center of the universe! From there it’s only gotten worse, from the medieval point of view. We aren’t the center of the universe because there is no center. Time depends on your reference frame, space is expanding in all directions, entropy is increasing, and, if theories about strings and dark energy are correct, we can only perceive a small part of our universe. For many, the obvious conclusion is that our current understanding of the universe leaves no room for the meticulous, joyous order of the medieval cosmos. Nothing is central, nothing is certain. Where is God if there is no neatly bounded Primum Mobile for him to encompass? This question reminds me of “Gather Us In,” a contemporary hymn that celebrates the light of God’s presence breaking into the world here and now, “not in some heaven, light-years away.” Certainly, the universe’s lack of a center or defined outer reaches combines with our belief in God’s omnipresence to suggest that God is to be found everywhere, rather than at a decorous distance from the more run-down, “imperfect” regions of creation. However, the scientific principles that offer solutions to so many of the universe’s mysteries can lead us to dismiss the very idea of a realm beyond our understanding, let alone a truly transcendent God. It seems plain that, when based solely on human reason and limited knowledge, medieval philosophy and modern cosmology both present opportunities for faulty reasoning. The former made medieval scholars insist on God-ordained immutability that (as we now know) never existed; the latter makes us prone to see no divine order at all. Where early philosophy had no explanation except God, present-day cosmology often seems to leave no room for God. History offers us no easy answers, but perhaps, as is often the case with the things of God, the correct path lies not in a half-hearted compromise, but in a synthesis that is far more radical than either position alone. How can we reconcile idealized philosophical constructs with rigorous scientific methods? For me, the answer lies in the poetic imagination of some of Christianity’s greatest writers. As an example, I’d like to offer two quotes that have influenced my view of existence as a created being and child of God. The first is from Book XI of Augustine’s Confessions (which I highly recommend—come for the juicy personal details, stay for the trippy discussions of time and memory), in which he expounds on the book of Genesis and the process of creation. “Let there be light,” Augustine believes, was not spoken once within time, tickling the air with its vibrations before fading away. Rather, through the person of the Son, the living Word, the impetus for creation has been spoken outside of time and resonates through all of time and space: (VII.9) Clearly You are calling us to the realisation of that Word—God with You, God as You are God—which is uttered eternally and by which all things are uttered eternally. For this is not an utterance in which what has been said passes away that the next thing may be said and so finally the whole utterance be complete: but all in one act, yet abiding eternally: otherwise it would be but time and change and no true eternity, no true immortality….Thus it is by a Word co-eternal with Yourself that in one eternal act You say all that You say, and all things are made that You say are to be made. You create solely by thus saying. Yet all things You create by saying are not brought into being in one act and from eternity.[i] Augustine argues that in character with God’s timeless nature, it is the eternal speaking of the Son as creative Word that sustains creation, representing God’s ongoing, active will for our existence. A similar theme can be divined from G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy, which chronicles his discovery of God as the true source of the wonder and joy that many of us remember only from fairy tales and early childhood. Addressing the total lack of wonder with which many adults come to view their daily lives and the world around them, Chesterton muses: But perhaps God is strong enough to exult in monotony. It is possible that God says every morning, "Do it again" to the sun; and every evening, "Do it again" to the moon. It may not be automatic necessity that makes all daisies alike; it may be that God makes every daisy separately, but has never got tired of making them. It may be that He has the eternal appetite of infancy; for we have sinned and grown old, and our Father is younger than we.[ii] In Chesterton’s joyful repetition and Augustine’s vision of the resounding Word, I see two perspectives on God’s joy in creation. The above passages certainly harmonize well with the emotional tone of the medieval celestial spheres, whose love for God renders them magnificent rather than monotonous. (I imagine that both thinkers would readily agree with the similarities, since Augustine lived in a geocentric world and Chesterton had profound respect for classical and medieval thought.) Unlike more rigid cosmic schemes, however, Augustine and Chesterton also admit the possibility of change—and more importantly, the ultimate futility of our predictions and expectations. In Chesterton’s view, the sun rises in a predictable pattern each day as it has done for billions of years not because it is inevitable, but simply because God has not yet chosen to do anything else with it. Augustine goes even further, stating that our very existence depends on God’s continued and sustaining pleasure. What we think of as natural laws and processes have not only been set in motion by God, but are contingent on his constant attention and approval. In some ways, this belief fits relatively well with the most cutting-edge discoveries of cosmology and physics, each of which seems to leave us with a greater awareness of our ignorance. We may not see changes in the laws of physics themselves, but we live in a changing universe and are finding ever more complexity in the quantum interactions and unifications of forces we once thought unrelated. On the other hand, claims that God can alter the very fabric of the universe on a whim can never be addressed or substantiated by science, and thus are understandably viewed with suspicion. As a Christian physicist, I’m striving to embrace the challenge of rejoicing in our inherent limits and contingency as creatures, forever looking to God for life. I take great joy in the progress physics has made in describing the cosmos since Ptolemy, Augustine, and Dante, but I also believe that God reserves the right to thwart my scientific expectations, to appear foolish to my human wisdom. If we ignore the divine transcendence that is one of the legacies of medieval theology, our work for God’s kingdom will be the poorer for it. Besides, I don’t know about you, but I like a little celestial music to go with my stargazing. [i] Augustine. (2006) Confessions, tr. F.J. Sheed. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing Company. [ii] Chesterton, G.K. (2012) The G.K. Chesterton Collection. Catholic Way Publishing. |

Monica Bennett is a freelance science writer in Corvallis, Oregon. She studied physics at the University of Dallas and Vanderbilt University, taking plenty of time along the way to feed her love of theology, linguistics, dancing, and other interests. Her passion for reading and discussing pretty much everything continues to lead her to new ways of understanding God and the universe.

|