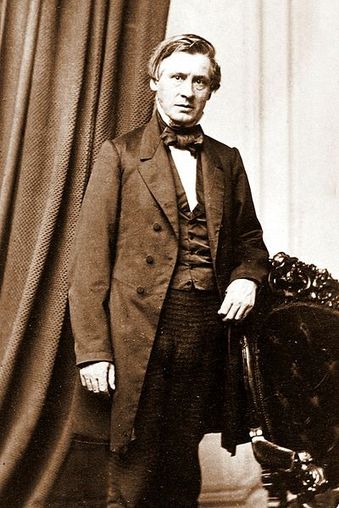

Asa Gray and the Emergence of Modern Biology

by Thomas Burnett

If we could choose anyone to represent the intersection of American science, evolution, and religion, there is no better candidate than Asa Gray. Though few people recognize his name today, Asa Gray was one of the most prominent American biologists of the 19th century, on equal footing with his European contemporaries Charles Darwin, Thomas Huxley, Joseph Hooker, and Louis Agassiz, and his brilliant research helped usher in modern era of biology in the United States. In the story that follows, we will examine Asa Gray’s innovative research, his role in American science, his reception of Darwin’s Origin of Species, and his view of Christianity. From humans to plants In the 19th century, there were precious few opportunities to become a professional scientist, and even for those who managed to do it, there was no direct educational path for them. At that time many of those who were curious about the natural world would usually study medicine or theology, both of which provided a strong intellectual foundation for scientific study. Asa Gray chose medical school, completing his training before his 21st birthday. At the same time, he taught himself natural history and became an expert in botanical research. After practicing medicine for a brief period, Gray dedicated his career to his strongest scientific passion-- plant biology. As he intellectually matured, Gray developed a scientific philosophy that pervaded his worldview. First of all, he conducted botanical research with a thoroughly empirical and materialistic methodology, an approach that set him apart from many of his peers. Second, concerning his own species, Gray believed that humans were a part of nature, not outside of it, subject to the same physical laws that that govern other organisms. Third, he maintained the biological unity of all human beings. Though we take this view for granted today, Gray lived at a time when people were still bought and sold as slaves. Some of Gray’s contemporaries argued that different races of humans were different species, and that some were naturally superior to others. In Asa Gray’s scientific career, his greatest achievement was conducting a comprehensive and systematic study of the plants of North America. Given the vast landmass and biodiversity on this continent, one can hardly imagine a more daunting task. Even worse, North America was still a largely unexplored continent, fraught with danger, disease, and violent encounters with Native Americans. This momentous project consumed Gray for more than 40 years. One of the dangers of specialization is that it relieves the scientist of the duty of asking big questions

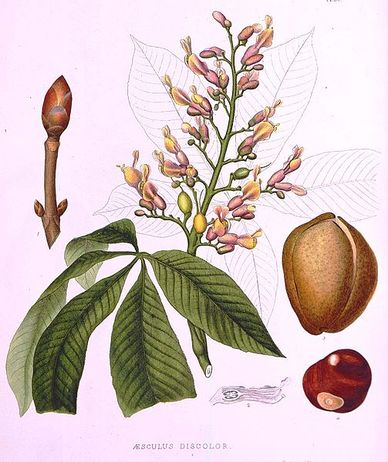

Plates Prepared for a Report on the Forest Trees of North America by Asa Gray

American Science

One hundred and fifty years ago, around the time of the Civil War, science was not the big business that it is today. In fact, when Asa Gray was approaching retirement in the 1870’s, there was still only one other full-time botany professor in the United States. The scientific community was small, and they benefitted greatly from associations like the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), founded in 1848, and the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), founded 1863. Visionaries like Gray opened entire research fields, and he developed botany into a rigorous discipline that would later be featured as one of the eight fundamental fields of science in the Great Hall of the National Academy. In an age when science had little institutional support, many great intellectuals felt obliged to develop laboratories and museums that would expand and support research for decades to come. Whereas Louis Agassiz built the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, Asa Gray built the botany department and research herbarium there. During his career, Gray observed that as science advanced, it became increasingly specialized. On the one hand, this specialization allowed scientists to gain vastly deeper knowledge of particular phenomena, but at the same time, they could also lose track of the larger picture. Gray warned, “One of the dangers of specialization is that it relieves the scientist of the duty of asking big questions, of facing up to the philosophical implications of his work.” Over the course of Gray’s lifetime (1810-1888), the philosophical issues surrounding biology became especially critical, and they continue to challenge us today. Origin of Species Asa Gray’s life is particularly interesting because his research career divides nearly evenly before and after 1859, the year that Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species appeared. When a radically new idea emerges within a scientific field, the older generation of scientists sometimes clings to the more established theories, since they made their careers in that context. Younger scientists, who have less personal stake in older theories, often embrace the innovate ideas and develop their field in new directions. But Asa Gray is unusual in that he was a leading scientist in both eras, producing excellent research before and after Darwin proposed evolution by natural selection. Before we launch into discussion of evolution, let’s take a look at the relationship between Gray and Darwin. The two first met in 1839, during Asa Gray’s first visit to Europe, when Gray was only twenty years old. They made a favorable impression on each other but did not reestablish contact until 1855, when Darwin wrote to Gray and asked him about plant distribution around the world. The two began regular correspondence after that, and each inspired the other in research and publishing. In fact, after 1860, Darwin’s research focused almost entirely on plants, Gray’s specialty. As scientists, they viewed each other as equals, with each deferring to the other’s area of expertise. Asa Gray’s refusal to take sides in this contentious debate upset both the religious conservatives and the radical popularizers of science, both of whom insisted that evolution implied atheism.

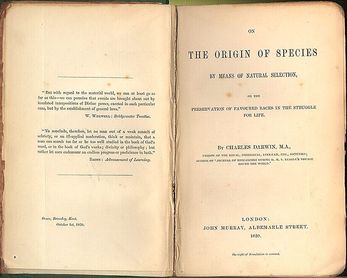

Opening pages of Darwin's Origin of Species

What happened when Origin of Species burst onto the scene? Gray responded by writing the first major review of Origin on his side of the Atlantic. After Darwin read it in The American Journal of Science, he wrote to Gray that it was “by far the most able which has appeared, and you will have done the subject infinite service.” In addition to defending his colleague in print, Gray spoke on behalf of Darwin’s theory in a series of meetings of the AAAS in 1859 and 1860. Gray was determined that Origin would get a fair reading from the scientific community, and he would not let Louis Agassiz and other naysayers shout it down. Furthermore, Gray took a leading role in negotiations to reprint Origin in the United States in 1860, ensuring that Americans could have the most newly revised and authoritative edition in their hands. In sum, Darwin benefitted tremendously from Gray’s efforts to defend his theory of evolution among American scientists.

And yet, if Gray was so instrumental to the reception of evolution in North America, why was he largely forgotten, while Thomas Huxley was immortalized as “Darwin’s Bulldog”? Part of the reason is that Gray lived in the United States, a cultural backwater during the 19th century. But an even bigger reason for Huxley’s enduring fame is that he loved the limelight and commanded great attention outside scientific circles. Gray, however, stayed out of public debate, preferring instead to focus on his research. Despite their theological differences, Asa Gray and Thomas Huxley had a lot in common. Both enthusiastically supported Darwin’s research and helped foster a positive reception of his theory in the English-speaking world. Both men insisted that science could not inform us in matters of metaphysics or religion, which they viewed as personal and independent of professional research. Neither Huxley nor Gray completely submitted to Darwin’s formulation of evolution by natural selection, and both criticized its weak points. Gray maintained that the cause of evolutionary change must be internal to the organism, not environmental or behavioral. But Gray’s notion would have to wait many decades to gain popularity because there was no science of genetics and little understanding of the mechanism of inheritance until the 20th century. Christianity In any general discussion of evolution, the topic of God arises. That was just as true in the 19th century as in our own time, and Asa Gray lobbied hard to establish that Darwin’s theory was not atheistic. He felt the question of whether or not life evolves should not be conflated with the issue of God’s existence. Instead, he felt each topic must be investigated using a methodology appropriate to the subject of inquiry. As a scientist, Gray insisted on the neutrality of science in matters of religion and metaphysics. As a human being, he had to deal with the same existential questions that confront us all. In 1835, a few years after completing medical school, Asa Gray made a decisive commitment to Christianity (much like Francis Collins of our own era). For the rest of his life, he was a regular churchgoer and member of a congregational church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When Origin of Species appeared in 1859, he found it incredibly stimulating to his botanical research, but never found it threatening to his faith. Gray did not feel it appropriate to use his fame to publically pronounce his faith, and when he was compelled to weigh in on religious issues, he always did so anonymously. The one exception he made was at the end of his career in 1876, when he published Darwiniana, a collection of excellent essays describing plant evolution. In that volume, he described himself as “one who is scientifically, and in his own fashion, a Darwinian, philosophically a convinced theist, and religiously an acceptor of the Nicene Creed, as the exponent of the Christian faith.” Ever a man of precision, Asa Gray did not ascribe himself to a particular religious denomination, but to a clear and unequivocal statement of faith. Legacy Asa Gray’s refusal to take sides in this contentious debate upset both the religious conservatives and the radical popularizers of science, both of whom insisted that evolution implied atheism. Gray, on the other hand, forged a different path—with his faith firmly grounded in the creeds of the early church, Gray conducted brilliant scientific research in evolutionary biology and maintained an unwavering commitment to Christ. If our contemporary culture wants to move beyond the perceived conflict between natural science and Christian faith, they could follow no better precedent than the one set by Asa Gray. Author’s Note: I am indebted to the research of A. Hunter Dupree, whose biography of Asa Gray served as the foundation for this essay. For more on how Gray reconciled evolutionary theory with Christianity, I recommend Asa Gray’s own book entitled Darwiniana (free electronic versions are available on the internet). |