No More Mealy Tomatoes

Big, ugly, beautiful tomato

Well, it’s happened. On one hand, I’ve been looking forward to this, and on the other hand, I’m really going to miss my tomatoes.

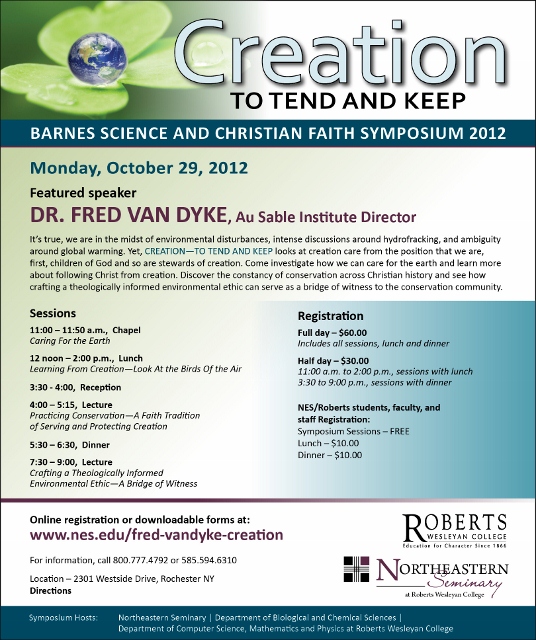

First frost brings with it a host of things we fall sentimentalists crave in the warmer months: the snug comfort of blankets over the knees, bursts of color in the treetops, soup… I love these things so much that if I don’t reign myself in, I’ll start to wax poetic and the whole point of this letter will be lost. I wanted to talk about tomatoes. It’s cold now. Any as-yet-unharvested fruit is rotting off its stalk. I mourn this moment because, having moved home to Kentucky from Boston in early June, my partner and I spent our whole summer in praise of the Kentucky tomato. Tomato salads. Capreses. BLT’s. Raw, with salt. All summer, not a day without one. For those readers who don’t already know, the Kentucky tomato is not at all like the New England tomato. I do not mean to belittle the northern tomato growers or their produce (most of it is excellent), but the summer sun just doesn’t beat hot enough up there for tomatoes to reach their full, sweet-tangy potential. It’s not tragic, per se, but to folks who are accustomed to the glorious complexity of the bulbous, many-colored varieties that truck in from local farms down south, it’s close. Even as a kid, I truly liked tomatoes, would even eat cherry tomatoes whole, but only in the past few years have I grown savvy enough to detect a difference in quality from month to month, location to location. It’s so apparent now, I can’t believe I never noticed it—but that’s the way of enlightenment, yes? Even when we’re only talking about tomatoes. My point is that I’m not going back. I will eat the less marvelous but still tasty hydroponic tomatoes the farmers here will grow through the winter so their communities don’t go without, but I refuse to be subjected to the spongy, fleshy things that pass for tomatoes in supermarkets every day. When it’s February, dark, and my sandwiches crave that bright acidic punch, I’ll make do with a pickle and dream of next June. They will be all the tomato-ier for the anticipation. Now, the metaphor you may have been waiting for isn’t coming. I really wanted to write about tomatoes, and seasons, and how blessed I feel to be back in a place that grows the things I love very well. (When my husband and I traveled to Costa Rica on our honeymoon, we felt the same way about avocadoes there. It was like we’d never tasted an avocado before we had them in a climate where they grow free and can be plucked fresh). In this issue of God and Nature, our contributors have tackled a variety of subjects, from how to hunt for baby galaxies, to the politics of research funding, to the birth of paleontology, and new thoughts on the old question of whether faith and science are compatible. What I see in all of them is unapologetic wonder, even incredulity, at the richness of the natural world—what Annie Dillard calls “extravagance!”—also, an abiding thankfulness that any of this is here at all, and that we humans are able to manipulate the once-wilderness to our needs. To feed and clothe our bodies, excite our spirits, power our homes and cars. We’ve come so far in a few centuries. It’s an amazing amount of technology that can get a fresh tomato on the market shelves in Louisville, Kentucky, in January. But while the lack of inherent “goodness” in that round red charlatan is transparent enough if you’re looking for it, other bittersweet advancements toward improving basic human comforts aren’t so easy to approach and understand. What should we do about clean energy—change our light bulbs? Trade in the clunker? Something more? And agribusiness. I don’t even like that word! How to avoid being part of a system that removes beaks from chickens in the name of mass production? How to decipher the equivocal labels on most of the packaged food we purchase? Examining these issues in any daily conversation is fraught with political peril, but it’s obvious that thinking Christians have some duty to do so. Commonly called “creation care,” it’s a new wave in the church that calls us to be responsible for, well, creation. For me and my family, buying fresh local tomatoes isn’t a big investment of time/energy/money in a system we can feel good supporting, but subscribing to a CSA (community supported agriculture), and committing to “slow food” as a way of life, is. Whether or not we decide to act immediately, or as fully as my friends Jesse and Hannah, a couple of young organic farmers trying to hew out a life off the grid, it’s important and troubling and healthy to think about these things. Peter Hess writes in his God and Nature column, “Clearing the Middle Path”: “It is questionable whether the earth can long support a population of seven billion energy-hungry and resource-guzzling members of species Homo sapiens… As a theologian deeply interested in science, I point out to my sons that the universe is ancient, dynamic, ever-evolving, and incomprehensibly vast. Change is an essential part of our world, for without change neither humans, nor plants and other animals, nor the geographical features that make our world exciting, would exist at all.” While the deviant in me smiles to think global climate change can’t be bad for tomatoes in Boston, I literally cringe to think harder about what that shift insinuates. Everything is connected—everything. Yes, I am afraid for the future. For the plants and animals that will not be able to adapt. For selfish items, like the rising cost of gasoline. But I am an optimist at heart, and I do believe on some level that discomfort, even suffering, can be a good and necessary thing. I won’t say I’m not going to miss the lavish comfort of a hot bath just for the sake of it—that day will come in my lifetime—but because I believe that the cost of such comfort manifests as complacence and ingratitude in all of us, I steel myself toward thoughts of harder times, deeper bonds, and awareness of the unimaginable blessing of simple things. —Emily Ruppel |