With All Your Mind

By Paul S. Kindstedt

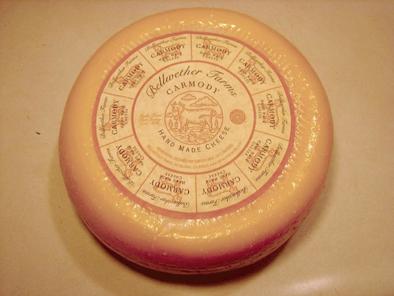

Cheese! Cheese!

What does it mean to love God with all your mind? I was raised in a conservative Christian home and my religious upbringing took place in evangelical churches where creationist thinking was largely taken for granted. By “creationist” I’m referring to the belief that God created the universe and all that is in it in six discrete supernatural and intentional creative acts, either over a period of six 24-hour days (new earth creationism) or spanning vastly longer time frames (old earth creationism).

From my earliest years I was academically motivated, always questioning, and ultimately destined to pursue a university career in Food Science as a cheese scientist. During my first year of college at the University of Chicago, I took a biology course on animal form and pattern taught by Charles Oxnard, a leading evolutionary biologist at the time. The evidential trains that Oxnard presented in support of evolutionary thinking impressed me. By the time I finished graduate school, little doubt remained in my mind about the basic tenets of evolution (descent with modification from common ancestors); it was difficult to conceive of another model that could integrate so many independent lines of evidence into a coherent understanding of the biological past. Clearly, specific details might be expected to shift as the science improved over time, but the basic scaffolding of evolutionary theory seemed solidly secure. As a conservative Christian who had recently taken permanent ownership of my faith and been baptized in an evangelical, creationist-oriented denomination, I now found myself with a seemingly irreconcilable internal conflict. Teetering on a razor-thin bridge that spanned a gaping chasm, I felt the strong pull of the familiar landscape behind me: my religious upbringing in Genesis literalism and creationism, and the theological concerns that follow when one moves away from literalism. At the other side of the chasm, my desire to be intellectually honest in the face of solid science, and fair to my academic colleagues in the biological sciences, beckoned insistently. How can a believer who comes to this conclusion live and worship within a Christian community that expects adherence to a literal interpretation of Genesis? And so I entered adulthood as a follower of Christ, secure in my faith yet compartmentalized as a Christian, remaining silent about my evolutionary views when among my evangelical brothers and sisters in Christ. I rationalized that silence was necessary to prevent division within the Body of Christ, that my evolutionary views did not compromise my Church’s Statement of Faith, and that I was not being deceptive or hypocritical, simply prudent. As the years passed I taught Sunday School, led Bible studies, became a Deacon (similar to Elder) in my Church, was married and, with my wife, dedicated our three children to the Lord and endeavored to raise them in the faith, all the while secretly struggling to formulate and come to terms with an interpretation of Genesis that would reconcile my conservative Christian theology with my evolutionary views; I especially wrestled with Genesis Chapters Two and Three. As incongruous as this double life became, it continued with no end in sight because my research and scholarship in cheese science seemed to have little bearing on my personal life as a follower of Christ. Unlike colleagues in various branches of biology whose expertise placed them unavoidably in conflict with literal Biblical creationism, my research had few evolutionary implications and there was no need for me to deal with the topic in my writings or teaching. In 2002, however, things began to unravel. Around that time, I became intrigued with the concept of using cheese science as a lens to reconstruct and interpret cheese history, which led to my developing a course called Cheese and Culture that surveyed the history of cheese and its place in western civilization. What especially excited and energized me about this course was the discovery that the history of cheese is deeply entwined with Judeo-Christian history, thus providing a platform to integrate my teaching with my Christian faith. My course Cheese and Culture eventually led to a sabbatical leave in 2009 to write a companion book of the same name, which was released in 2012. One of the premier questions that I needed to address in my course and book was when and where did cheesemaking begin for the first time. As I searched the scholarly literature for clues, the results kept pushing the time frame further and further back, ultimately all the way back to the Paleolithic-Neolithic transition, and suddenly I was faced with questions of human development that demanded an evolutionary context. There was no ducking the issue any more; my scholarship was now linked at the hip to evolution, and in order to pursue my book project I had to be willing to formulate a narrative based on the best science and scholarship available, wherever it led; to do otherwise would be intellectually dishonest. As I crafted a proposed narrative for the origin of cheese, I pondered the remarkable changes in global climate that marked the transition from the Pleistocene to Holocene around 12,000 years ago, which set into motion the stable Mediterranean weather patterns that transformed the upper Fertile Crescent into a comparative Garden of Eden. I marveled at the abrupt and dramatic changes in human behavior that occurred concurrently in this region. The ascendency of the sense of self and of the family as the foundational social unit, of spiritual awareness and religious practice, and of creativity, artistic acuity and technological advance all seemed to herald the arrival of the human species at a singular destination: the race of mankind that we take for granted today, alone in all of biology, transparently reflecting the image of God. I was also intrigued by the rapid appearance of crop cultivation and domestication, soon followed by the herding and domestication goats, sheep and cattle. The decrease in birthing interval that accompanied the sedentary lifestyle of these Neolithics and increase in child-bearing that now confronted women, and the agricultural treadmill that men were now beholden to in the face of relentless population growth, failing soil fertility, deforestation and erosion, and the endless battle against the weed also struck a resonant chord. I found myself stunned by the parallels that emerged with the Genesis account of creation in Chapters 2 and 3; not the literal account but a more nuanced pictorial account that arises when one analyzes Genesis without the strictures of literalism. And I marveled to find secular scholars who argued that Genesis might reflect an ancient memory of what actually happened, an account to be taken seriously. This was a story that I wanted to share with my conservative evangelical brothers and sisters in Christ, especially with youth who were struggling with creationism and evolution. It was then that my eyes were open to the dishonesty that I had been practicing towards my faith community all those years by remaining silent on the issue of evolution. There was only one way forward that I could see, and that was to seek the counsel of my Pastor. As I shared my excitement about this book project with Peter, I also expressed my anguish over its potential to be divisive within our Church Family and the Body of Christ more broadly, and wondered what to do. Peter gently reminded me that a Christian must be honest, and in doing so he gave me permission to wrestle with this dilemma. And so I have wrestled, these past eight years, asking God for wisdom as I pondered the deepest theological fears that evolution strikes in the hearts of Biblically conservative Christians: doctrinal questions of original sin, the fall of man and subjection of nature to futility; God’s goodness; the absolute necessity of Christ’s atoning sacrifice on the cross; the New Testament’s apparent endorsement of a literal interpretation of Genesis; the inerrancy of the Bible and our charge to “guard the good deposit”; the slippery theological slope that leads to the Jesus Seminar; and on and on. Although a vast amount of scholarly literature has been published in this area, I am not a theologian and my attempts to systematically analyze and resolve the issues were humbling. About a year ago, rather unexpectedly, I developed an intense desire to read the works of C.S. Lewis, everything that I could get my hands on. As I poured over Reflections on the Psalms, Miracles, and The Problem of Pain, I marveled to find that Lewis had wrestled with many of the same theological issues, questions of Biblical interpretation, and evolutionary contexts that now preoccupied me. Lewis was a man of impeccable intellectual honesty and his writings encouraged me to wrestle onwards, and to reach out to my evangelical brothers and sisters in Christ who may be struggling as I have struggled. I can’t help but wonder how many other believers in our Evangelical churches are trying to follow God’s calling yet feel isolated and discouraged by their own inner conflict, as well as the external conflicts that often simmer beneath the surface our Churches and families over creationism and evolution. For me, the issue is not the science, which I believe is clear, or the orthodox theology, which I believe is non-negotiable, but their compatibility. With the help of my Pastor, who gave me permission to wrestle with this issue, and Lewis’s musings, I have come to terms with my evolutionary views and my inerrant view of Scripture and orthodox Christian theology. No, I don’t have all the answers, only those that I believe are essential and non-negotiable to the teachings of Scripture and the historic orthodox creeds. Perhaps of equal importance, I am at peace that not all believers will come to the same conclusions that I have; and not all believers need to agonize over evolution. My parents didn’t. They were content to accept that if the Bible says six days of miraculous creative acts, or billions of years of miraculous creative acts, then so be it. They lived and died secure in that faith, and for all I know they may be right about the six days and miraculous acts, despite the very different picture that credible science overwhelmingly currently paints with respect to biological diversity; we will find out when we get to Heaven. In the meantime, my concern is not about changing anyone’s mind about evolution, but it is about contemplating what it means to love God with all of one’s mind. I have come to the conclusion that different Christians may express such love differently. My parents, who grew up in conservative Christian homes during the Depression and never had the opportunity to attend college (well, Dad did complete one year at Bob Jones College before WWII intervened), couldn’t begin to fathom the conflict that I was facing internally. For them, evolution was completely implausible, requiring a ridiculous leap of faith that made no sense when stacked up against the truth of Scripture. Their choice was simple and clear. How could I expect them, and how could they expect me, to love God with all our minds in precisely the same way? The important point from my vantage is that my parents and I walked hand-in-hand in our love for Christ, and we walked in lockstep affirmation of the orthodox tenets of the faith, even though our faith journeys looked different. During the final two decades of my parents’ lives my relationship with them was closer and more fulfilling than at any other time in my life, in part because we were able to move beyond simply “agreeing to disagree” to genuinely appreciating and admiring one another’s faith in Christ. We were at unity despite our diversity. Perhaps there is a lesson to be learned here, and a conversation to be had more broadly within the Evangelical Church in America, concerning what it means to love God with all your mind, and what the expression of that love should look like individually and corporately within the Body of Christ. |

Paul Kindstedt is a Professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of Vermont. His research over the past 30 years at Vermont has focused on the chemistry, structure and function of cheese. He has authored or co-authored over 120 peer-reviewed journal articles and invited conference proceedings, numerous book chapters and 2 books (Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization and American Farmstead Cheese: The Complete Guide To Making and Selling Artisan Cheeses).

Over the years Paul has served as Associate Director of the Northeast Dairy Foods Research Center, Co-Director of the Vermont Institute for Artisan Cheese, and faculty advisor to the Navigators and Intervarsity Christian Fellowship student groups on campus. He currently serves on the Board of Directors of the American Dairy Science Association and the Vermont Dairy Industry Association. Paul and his wife Christina are blessed with three children who are the joy of their lives. |