God and Nature Spring 2021

By Juuso Loikkanen

The belief that God actively acts in the world, “sustaining all things by his powerful word” [1], has been fundamental to Christian theology throughout its history. But how does God do the trick? How does he influence the events occurring in our universe? And is it even important for Christians to try to understand how God acts?

According to biologist and prominent atheist Richard Dawkins, believing in a deistic god who does not interact with his creation would be “watered-down theism” [2, p. 18], a distortion of the Christian faith. If Christianity is to gain any credibility in the contemporary world, Christian theology must have some kind of an answer to how God influences our world. Perhaps in order to provide an answer to challenges like this, divine action has become an increasingly popular topic in the dialogue between science and theology during the last few decades.

The belief that God actively acts in the world, “sustaining all things by his powerful word” [1], has been fundamental to Christian theology throughout its history. But how does God do the trick? How does he influence the events occurring in our universe? And is it even important for Christians to try to understand how God acts?

According to biologist and prominent atheist Richard Dawkins, believing in a deistic god who does not interact with his creation would be “watered-down theism” [2, p. 18], a distortion of the Christian faith. If Christianity is to gain any credibility in the contemporary world, Christian theology must have some kind of an answer to how God influences our world. Perhaps in order to provide an answer to challenges like this, divine action has become an increasingly popular topic in the dialogue between science and theology during the last few decades.

"God’s actions are very probably incomprehensible to us." |

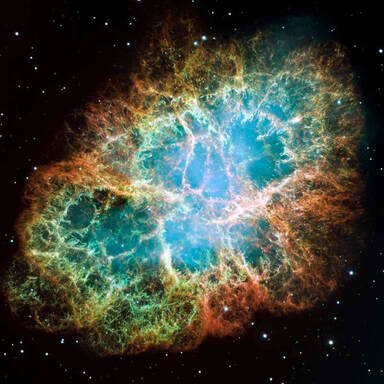

There have been many attempts to reconcile God’s actions with the results of natural sciences. One example is the so-called quantum divine action theory, according to which God can bring about effects observable by humans by controlling a multitude of seemingly insignificant and indeterministic quantum events. This is based on (one version) of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum physics, which states that there exist many possible physical states of which only one, a seemingly arbitrary one, actualizes. Although human observes cannot perceive any predictability in quantum systems, an almighty God would be able to adjust the microscopic events appropriately to make things happen on a wider scale, and thus steer the course of history without us humans noticing [3] [4].

The important word here is might. Even if it were theoretically possible that God might act through quantum events, how can we know whether this actually is the case? How can we move from might to is, from mere possibility to anything concrete? More generally, if there are some physical processes that seem to leave room for hidden actions undetectable by humans, is it smart to assume that God is involved in these processes? If God’s ways are higher than our ways, as the Bible says, would it not be wiser just to accept that he moves in mysterious ways? If we accept the basic teaching of Christianity that humans cannot properly understand God’s nature, how could we hope to understand how he works in his creation?

The quantum divine action theory itself has attracted critique. It seems that there exist no known physical processes that could amplify the microscopic quantum fluctuations into the macroscopic level. It is possible that the opposite is true. Philosopher of science Jeffrey Koperski has pointed out that “nature has firewalls in place that keep random events at the quantum level from influencing the realm of our everyday experience,” and, consequently, “if God governs the universe by way of quantum randomness alone, then we are left with something close to deism” [5, p. 389]. As far as I know, there are no other scientifically credible theories of divine action that could reconcile the findings of contemporary physics with the Christian teaching of God who actively acts in the world.

Physicist and theologian Nicholas Saunders has claimed that contemporary theology is “in crisis” since it cannot in any credible manner account for how God could act in the world. Saunders reminds us that “a wide range of doctrine is dependent on a coherent account of God’s action in the world,” but “we simply do not have anything other than bold assertions and a belief” that divine action takes place [6, p. 215]. Of course, if the progress of science in the future offered new theories that could be reconciled better with non-interventionist actions of God, such theories should be considered carefully. Yet it is difficult to imagine how we could come up with a theory of divine action that would reach beyond theoretical possibility, beyond theoretical speculation about what God might do.

Is Saunders correct that contemporary theology is in crisis? If we do not know how God acts, does this undermine the credibility of Christianity or Christian theology? I do not think so. Although Christianity teaches that God acts actively in the world and is accessible to humans, it also teaches that God is the ultimate mystery. Christians can respect the mystery and still continue to believe that God is actively present in the world.

I have argued, first, that it might be impossible to ever construct a scientifically credible detailed theory of divine action, a theory that would go beyond theoretical compatibility or possibility. Proving how God acts in the physical world might be too challenging a task for humans to complete. Attempts to formulate theories of divine action have typically been based on the assumption that God’s activity is of the same kind as the activity of humans. In other words, these theories presuppose a univocal understanding of divine and creaturely causality. In the light of seeing God as the ultimate mystery, this assumption might need to be reconsidered. It is possible that God’s actions are ultimately incomprehensible to us.

Second, I have claimed that the inability to offer a detailed account of divine action does not mean that theology is in crisis. The reason is the same as above: God’s actions are very probably incomprehensible to us. Theology does not stand and fall with its ability to offer a scientifically detailed account of divine action. Even if we do not currently have a scientifically tenable theory of divine action—and even if we are never able to come up with one—it does not mean that theology has failed.

Just as a God who did not interact with the world would not be much of a God, perhaps a God who did not conceal his actions from humans would not be much of a God. It is quite possible that we can never fully “fathom the mysteries of God” [7]. Does this mean that trying to make sense of divine action is futile? I do not believe so. I do not think that we should stop searching for an answer—if not for any other reason, then because speculating about divine action is a fascinating field of theological inquiry.

[1] The Holy Bible: New International Version, Hebrews 1:3.

[2] R. Dawkins, God Delusion. London: Bantam Press, 2006.

[3] R. J. Russell, “Divine Action and Quantum Mechanics: A Fresh Assessment” — R. J. Russell, P. Clayton, K. Wegter-McNelly & J. Polkinghorne (Eds.), Quantum Mechanics: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action, Vatican City & Berkeley: Vatican Observatory & The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, 2001, 293–328.

[4] N. C. Murphy, “Divine Action in the Natural Order: Buridan's Ass and Schrödinger's Cat” — F. L. Shults & N. C. Murphy & R. J. Russell (Eds.), Philosophy, Science and Divine Action, Leiden: Brill, 2009, 325–357.

[5] J. Koperski, “Divine Action and the Quantum Amplification Problem” – Theology and Science 13(4), 379–394.

[6] N. Saunders, Divine Action and Modern Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[7] The Holy Bible: New International Version, Job 11:7.

Juuso Loikkanen, PhD, is a post-doctoral researcher in Systematic Theology at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu, Finland.

The important word here is might. Even if it were theoretically possible that God might act through quantum events, how can we know whether this actually is the case? How can we move from might to is, from mere possibility to anything concrete? More generally, if there are some physical processes that seem to leave room for hidden actions undetectable by humans, is it smart to assume that God is involved in these processes? If God’s ways are higher than our ways, as the Bible says, would it not be wiser just to accept that he moves in mysterious ways? If we accept the basic teaching of Christianity that humans cannot properly understand God’s nature, how could we hope to understand how he works in his creation?

The quantum divine action theory itself has attracted critique. It seems that there exist no known physical processes that could amplify the microscopic quantum fluctuations into the macroscopic level. It is possible that the opposite is true. Philosopher of science Jeffrey Koperski has pointed out that “nature has firewalls in place that keep random events at the quantum level from influencing the realm of our everyday experience,” and, consequently, “if God governs the universe by way of quantum randomness alone, then we are left with something close to deism” [5, p. 389]. As far as I know, there are no other scientifically credible theories of divine action that could reconcile the findings of contemporary physics with the Christian teaching of God who actively acts in the world.

Physicist and theologian Nicholas Saunders has claimed that contemporary theology is “in crisis” since it cannot in any credible manner account for how God could act in the world. Saunders reminds us that “a wide range of doctrine is dependent on a coherent account of God’s action in the world,” but “we simply do not have anything other than bold assertions and a belief” that divine action takes place [6, p. 215]. Of course, if the progress of science in the future offered new theories that could be reconciled better with non-interventionist actions of God, such theories should be considered carefully. Yet it is difficult to imagine how we could come up with a theory of divine action that would reach beyond theoretical possibility, beyond theoretical speculation about what God might do.

Is Saunders correct that contemporary theology is in crisis? If we do not know how God acts, does this undermine the credibility of Christianity or Christian theology? I do not think so. Although Christianity teaches that God acts actively in the world and is accessible to humans, it also teaches that God is the ultimate mystery. Christians can respect the mystery and still continue to believe that God is actively present in the world.

I have argued, first, that it might be impossible to ever construct a scientifically credible detailed theory of divine action, a theory that would go beyond theoretical compatibility or possibility. Proving how God acts in the physical world might be too challenging a task for humans to complete. Attempts to formulate theories of divine action have typically been based on the assumption that God’s activity is of the same kind as the activity of humans. In other words, these theories presuppose a univocal understanding of divine and creaturely causality. In the light of seeing God as the ultimate mystery, this assumption might need to be reconsidered. It is possible that God’s actions are ultimately incomprehensible to us.

Second, I have claimed that the inability to offer a detailed account of divine action does not mean that theology is in crisis. The reason is the same as above: God’s actions are very probably incomprehensible to us. Theology does not stand and fall with its ability to offer a scientifically detailed account of divine action. Even if we do not currently have a scientifically tenable theory of divine action—and even if we are never able to come up with one—it does not mean that theology has failed.

Just as a God who did not interact with the world would not be much of a God, perhaps a God who did not conceal his actions from humans would not be much of a God. It is quite possible that we can never fully “fathom the mysteries of God” [7]. Does this mean that trying to make sense of divine action is futile? I do not believe so. I do not think that we should stop searching for an answer—if not for any other reason, then because speculating about divine action is a fascinating field of theological inquiry.

[1] The Holy Bible: New International Version, Hebrews 1:3.

[2] R. Dawkins, God Delusion. London: Bantam Press, 2006.

[3] R. J. Russell, “Divine Action and Quantum Mechanics: A Fresh Assessment” — R. J. Russell, P. Clayton, K. Wegter-McNelly & J. Polkinghorne (Eds.), Quantum Mechanics: Scientific Perspectives on Divine Action, Vatican City & Berkeley: Vatican Observatory & The Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences, 2001, 293–328.

[4] N. C. Murphy, “Divine Action in the Natural Order: Buridan's Ass and Schrödinger's Cat” — F. L. Shults & N. C. Murphy & R. J. Russell (Eds.), Philosophy, Science and Divine Action, Leiden: Brill, 2009, 325–357.

[5] J. Koperski, “Divine Action and the Quantum Amplification Problem” – Theology and Science 13(4), 379–394.

[6] N. Saunders, Divine Action and Modern Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

[7] The Holy Bible: New International Version, Job 11:7.

Juuso Loikkanen, PhD, is a post-doctoral researcher in Systematic Theology at the University of Eastern Finland in Joensuu, Finland.