"Great Gravity" is featured every edition of God & Nature magazine, and tells the story of BNL physicist Bill Morse's journey through the world of muons and quarks, colliders and bubble chambers, with the heart of a committed Catholic and longtime-teacher of Sunday school. Read the first post in this series here.

The Grade School Years Norman Rockwell's rendition of a forlorn grade school boy

by Bill Morse Munjoy Hill was a tough neighborhood. There was a bottom of the hill gang, and our gang, which was at the top of the hill. When I was about six years old, the bottom of the hill gang came up to the top of the hill, and a fight broke out. After that, skirmishes occurred several times a year. Once, the bottom of the hill gang came up, but our gang wasn't together—there was just me. They started chase. I ran for the nearest sanctuary, but barely made it into our apartment, before they, too, reached the front door. No one was home, so the bottom of the hill gang followed me inside. Terrified of what might happen, I ran out the back door with them still following me, and somehow, I eventually out-ran them, or they lost interest. We were, after all, six. Things stayed like that for a pretty long time. The turning point came when we were all together at the top of the hill, fighting as usual. A boy in the bottom of the hill gang picked up a cobblestone. He took the cobblestone, chucked it, and hit Johnny square on the head. Everyone just stopped, shocked. But Johnny seemed okay—at least, he wasn’t screaming, so we kept fighting. Then blood started coming out from under his baseball cap. In the absence of six-year-old gang warfare, life in Scarborough was pretty good.

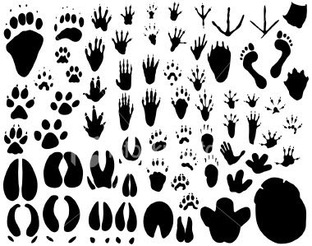

Cub Scout stuff: footprints of North American animals

This was the episode that finally convinced my mother, who convinced my father, that we should move to Scarborough. Of course, I didn't want to move, because all my friends were on Munjoy Hill. I just thought having enemies that physically brawled with you were a fact of life that you had to deal with.

In the absence of six-year-old gang warfare, life in Scarborough was pretty good. In 4th grade, our teacher told us we would have one hour of science a week. I thought, “Great, I've been waiting all my life!” (Or, at least, ever since I knew approximately what science was about). When we got our science textbook, I opened it up, and the first thing I saw was a picture of footprints of different animals. I had already learned about footprints in Cub Scouts—this was badge-earning stuff, not science! Finally, in seventh grade, we had our first real science course. The book was great! The teacher was great! I knew science was just as interesting as I had hoped it would be. In eighth grade, the book/ teacher weren't as great. In high school, it got even less great. Science was my favorite subject even before I’d taken a single class—I couldn’t seem to catch a break. It was in mathematics that I got my first taste of discovery through logic and observation. It started in sophomore geometry, with pretty boring stuff—mostly definitions of triangles, parallel lines, skew lines, etc. Then we got to the Pythagorean Theorem: The hypotenuse squared equals the sum of the squares of the sides for a right triangle. I sat down, covered up the proof in the book, and proved it myself. I felt that I was a different person from the day before! An overwhelming sense of the power and beauty of new knowledge rushed over me. This wasn't like my Civics class, which by the way I also loved, for the frequency with which we uttered the following sentence, "I disagree with what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." Yet the Pythagorean Theorem was something that God, or Nature, had said—it was non-negotiable. Of course, later I learned that the Pythagorean Theorem is only true if space-time is flat, which as it turns out, it isn't. However, when I learned laws that turned other laws upside down, it was again the same thrill! Unfortunately, I also discovered through observation that no one in my class felt the same way. Most of them thought that cars and baseball were interesting, and the Pythagorean Theorem was boring. I thought that cars and baseball were interesting, but that this was something much, much more interesting. At first I assumed I was just weird, that I was the only person in the world who felt that laws and proofs were exciting discoveries years and years after they’d been made. When I got to university, I found out that about 1% of the students there thought the same way. They were all in my math or physics classes. Read the next post in this series here.

|