A Philosophical Influence from the Scientific Revolution on Scientific Judgment by R. Scott Smith

The practice of science depends extensively upon empirical observations. Yet data needs interpretation, and we make judgments based upon theories and conceptual schemes. In this essay, I will explore how a key philosophical factor we have inherited from the Scientific Revolution – its embrace of nominalism – significantly shapes scientific judgment, or interpretation. Yet I will also try to show that if nominalism were true, it actually would undermine scientific practice – thus, scientific practice and judgment should not presuppose it. However, this finding also suggests that there is more to what is real in creation than what we can know empirically, which has major implications for scientific judgments.

Aristotelianism vs. the Scientific Revolution

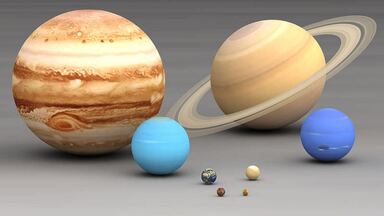

During the Middle Ages, the Aristotelianism of the Scholastics stressed metaphysics, especially real, immaterial, and universal qualities. For example, a universal would be a quality, or property, that is “one-in-many.” Literally, many particular, individual objects or things can exemplify the very same one quality or set of qualities. There could be many specific instances of, say, the color red in many particular tomatoes, or the rectangular shape in many particular tables. Plato called these universals “forms.” Moreover, on that view, universals have “essences”; for example, a triangular shape must have three angles, or it is not a triangle. A moral virtue like courage must be a character quality, or else it is not a moral virtue; it could not be what it is and turn out to be a color, shape, etc. These essences are things something must have, or else they cannot exist, and on Aristotelianism, they would be immaterial. They are not conventions or words that humans have devised; rather, essences exist apart from how we conceive or talk about things. Due in part to this emphasis upon universals and their essential natures, Aristotelianism lent itself to a more a priori (in-principle), deductive approach to science. The Scientific Revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries repudiated this philosophy, and natural philosophers developed a more a posteriori (experiential, observational) approach. Pierre Gassendi and Thomas Hobbes tended to embrace mechanical philosophy, according to which they (along with Kepler) conceived of the universe as a large-scale machine. Gassendi and others also utilized Greek atomism, in that they treated the material world as made up of atoms in the void, with atoms being ultimate. Putting these two views together, the mechanical atomists of the period included scientists such as Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei, Robert Boyle, and Isaac Newton, besides the philosophers Gassendi and Hobbes. However, those of this period tended to exempt from their atomism a “spiritual” world, which could include things such as the mind, soul, angels, and God. For example, according to Boyle, our spiritual faculties needed to be exempt because mechanical philosophy could not explain them. Further, Galileo and Boyle treated matter as having just “primary” qualities, such as size, shape, quantity, and location. In contrast, so-called “secondary” qualities, such as colors, tastes, or odors, were not properties of matter, but either were subjective qualities in the mind of an observer, or just names or words that people used according to linguistic conventions. For Boyle, secondary qualities and Aristotelian universals were unintelligible due to his conceptions of what is real in the material world. The Rise of a New Scientific Methodology Over time, a new scientific methodology arose that embraced empirical observation of concrete, material, and particular things. Without Aristotle’s universals, these material particulars would not have essences that necessitated certain causal effects. Instead, the new methodology embraced contingent causes and induction. These causes were contingent in that they did not follow by logical necessity from a thing’s essence. Rather, only empirical observation could establish these causes and their effects. In the face of empirical problems that confronted Aristotelianism, this new methodology represented a key advancement in that it stressed the importance of empirical observation of the world, rather than relying overly upon metaphysical theories. In its rejection of Aristotelianism and universals, these natural philosophers and scientists focused on particular objects. In fact, they sought to avoid introducing universal qualities and essences, which would not be primary qualities. Following in the same direction of the fourteenth-century theologian, William of Ockham, they embraced nominalism. In nominalism, there are only particular, individual qualities or objects. For example, while we may call many things by the name “atom,” there is nothing literally in common between them, lest universals exist. Moreover, on nominalism, all qualities are located in space and time, which suggests they are material and empirically observable. In contrast, at least in Plato’s case, universals themselves are abstract (i.e., they are not located in space and time), whereas their instances are spatially and temporally located. Nominalism therefore fit well with the emphasis upon empirical observation and inductive inferences that arose during the Scientific Revolution and has stayed with us through today. Now, according to nominalism, since all qualities are just particular, that implies they are simple. That is, they are just one thing, and not composed of additional things. For instance, while there are things like white-snow, or white1, white2, white3, there is no literal color white that these particular things all have in common. Similarly, there could be triangle1, triangle2, and triangle3, but not some common triangularity that these three things all share, for that would seem to be a universal, a one-in-many. If these things did share something in common, they would not seem to be simple; they would seem to be a quality (white, or triangularity) plus some individuator (1, 2, 3, etc.). Now, we may treat, or conceive of, such things as composed of two entities – namely, the quality plus an individuator. Nevertheless, according to nominalism, in reality each one itself is only one thing. However, there is a problem with this view. If each of these things is, in reality, just one thing, and not more, then it seems we can eliminate either the individuator or the quality without any loss in reality – i.e., in the thing itself. Suppose we eliminate the individuator; then, we seem to have an undifferentiated, universal quality, white or triangularity, which brings universals back into the mix. On the other hand, we could eliminate the quality; but that seems to leave us with just an individuator – but of what? It seems these individuators would not have any qualities, at least that we can observe empirically. It would be like labeling each white instance with the individuator “this,” as in this white instance. However, without the quality white, we seem left with just “this.” However, this what? That identifies, and seems to speak, of nothing. Nominalism and Modern Science Now, let us apply this critique of nominalism to scientific practice and judgment. If everything in the material world really is just particular or individual, then we seem to lose all qualities (at the least, all empirically observable ones). There would be nothing for scientists to observe – for example, no geometric shape that a space capsule, at a point in space and a given acceleration, will follow in order to reenter earth’s atmosphere; or, no qualities in the elements that allow us to determine the criteria for one element to bond with another. Worse, it also seems there would not even be scientists to make observations, for “we” would not have qualities either, such as ones to see, think, form hypotheses, etc. There will not be any “brute” facts of reality because nominalism cannot ground them. Nevertheless, that is not how we experience the world. Moreover, science works – scientists have made many incredible discoveries and developments over the centuries, and these discoveries seem to be occurring at an accelerating pace. Scientists develop new, helpful technologies; researchers make significant advancements in medicine; and so on. While science has pragmatic importance, it does not seem that science could work if everything is particular – that is, if nominalism is right and there are no universal qualities with their essential natures. It seems that science “works” because universals need to exist, both in the world under observation and in the knowers. Indeed, we can investigate the material world, but it seems it is unwarranted to conclude that it is just made of matter. Science has earned much prestige through empirical investigations of the world. However, we should notice that these empirical discoveries did not depend upon the truth of nominalism (or mechanical atomism). Suppose universals and their essences exist. If so, there still could be an empirically knowable world with particular instances of colors, shapes, locations, etc. Therefore, by focusing in science on empirically observable qualities, we still could know those things that are true about them. The existence of universals would not impede such a scientific methodology. Nevertheless, those empirical truths alone would not have anything to say against the existence of (for instance) the soul, or essences. Moreover, if the material aspects of the universe operate according to natural laws, that fact alone does not rule out in principle the existence of immaterial things, including such laws themselves. Importantly, science with its empirical focus does not rule out the existence of immaterial realities. Rather, the joining of science to nominalism (and mechanical atomism) has served to undermine belief in what is immaterial. Nominalism has shaped scientific interpretation significantly, yet it seems untenable in its own right. Thus, the move made in the Scientific Revolution to embrace it and reject Aristotelian universals actually serves to undermine scientific practice. While there was an over-reliance in Aristotelian science upon metaphysical theories and corresponding deductions without also stressing empirical observation of the world, it seems that scientific practice actually depends upon the existence of universal qualities. If so, then the received practice of interpreting and judging observable data as being simply material particulars without immaterial universals with essences seems unwarranted. For Further Reading: Chalmers, A. (2014). Atomism from the 17th to the 20th Century. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atomism-modern/. Del Soldato, E. (2016). Natural Philosophy in the Renaissance. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/natphil-ren/. Galilei, G. (1957). Il Saggiatore [The Assayer]. (S. Drake, Trans.). In Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo. New York: Doubleday & Co. Retrieved from https://www.princeton.edu/~hos/h291/assayer.htm#_ftn19. Klein, J. (2012). Francis Bacon. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/francis-bacon/. Moreland, J. P. (2001). Universals. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Smith, R. S. (2017). Craig’s Nominalism and the High Cost of Preserving God’s Aseity. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 9:1, 87-108. |

R. Scott Smith, PhD, is professor of philosophy and ethics in Biola University’s MA Christian Apologetics program. He is the author of Naturalism and Our Knowledge of Reality: Testing Religious Truth-claims (Routledge, 2012); In Search of Moral Knowledge: Overcoming the Fact-Value Dichotomy

(InterVarsity Press, 2014); and other articles on nominalism and knowledge. |