God and Nature Summer 2019

By Sarah Salviander

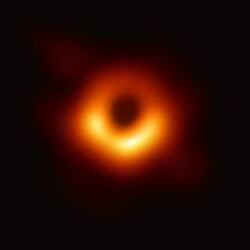

When the Event Horizon Telescope team released the first-ever image of a supermassive black hole in April of this year, it was met around the world with a sense of incredible wonder and excitement. Here was the silhouette of the monster at the heart of a giant galaxy 55 million light-years away, a triumph of human ingenuity and a planet-sized telescope. For days, news and social media were jam-packed with the donut-shaped visage of M87’s black hole and with links to articles and videos attempting to explain how in the world scientists could possibly take a picture of the invisible.

While billions of people were amazed and intrigued by the image of a black hole, there were some who responded in a strangely negative way. They accused scientists of faking the whole thing, and they expressed deep skepticism about the existence of black holes. I tried to communicate in an objective and scientific manner with some of these people in the hope of convincing them that the science was sound and black holes most likely do exist, but I was met with a stone wall of resistance.

When the Event Horizon Telescope team released the first-ever image of a supermassive black hole in April of this year, it was met around the world with a sense of incredible wonder and excitement. Here was the silhouette of the monster at the heart of a giant galaxy 55 million light-years away, a triumph of human ingenuity and a planet-sized telescope. For days, news and social media were jam-packed with the donut-shaped visage of M87’s black hole and with links to articles and videos attempting to explain how in the world scientists could possibly take a picture of the invisible.

While billions of people were amazed and intrigued by the image of a black hole, there were some who responded in a strangely negative way. They accused scientists of faking the whole thing, and they expressed deep skepticism about the existence of black holes. I tried to communicate in an objective and scientific manner with some of these people in the hope of convincing them that the science was sound and black holes most likely do exist, but I was met with a stone wall of resistance.

"Both God and black holes are unseen, mysterious, and frighteningly powerful to a degree that makes some people very uncomfortable." |

I had encountered this same reaction to black holes several years before in the form of a grumpy email from a fellow in Australia who cited a recent journal paper of mine and stated, “You do realize there’s no such thing as black holes, don’t you?” Well, no. I didn’t. He claimed he had mathematical proof of their impossibility. I did not ask to see it but instead countered by asking what he thought of the evidence that strongly pointed to the existence of black holes. He waved it away. I realized at that early point in my career as a scientist that there really are people who are not motivated by a sincere need for the truth.

Since that initial experience, I have encountered several more skeptics whose rejection of black holes is rooted in their rejection of broader modern scientific theories like big bang cosmology and the standard model of particle physics. Black holes in particular draw their ire, because, admittedly, black holes are pretty weird, and they get a lot of attention.

Though I do not completely understand their motives, I have come to better understand what these science skeptics represent. The hostility they express is a visceral reaction to being pushed past their emotional and cognitive comfort zones. They appear to be people who do not like things that are invisible. Their basic argument is never much better than “I’ll never see or touch a black hole; therefore, they don’t exist.” When presented with compelling evidence and mathematical arguments for the existence of these unseen entities, they consistently reject even the most trustworthy science on the basis that there could be alternative explanations, no matter how implausible.

Almost everyone has one of two very different worldviews based on whether or not they believe in God. Most of us become deeply invested in the worldview we’ve adopted and are inclined to be resistant to any evidence that threatens it. I suspect that most black hole skeptics, certainly the ones I have encountered, are deeply suspicious that scientists are trying to impose a false worldview on them. What that worldview is I do not quite know, but it contains a universe that is entirely material, self-evident, touchable, and understood without the help of modern scientific theories.

After attempting to discuss science with black hole skeptics, it is obvious to me that their hostility is a result of something more than just cognitive discomfort and strong emotions about what they believe. There is a profound lack of humility at work that reaches the point of arrogance and self-delusion. Black hole skeptics think they have no need to consider the evidence other people have. They believe that their intellectual superiority makes them qualified to be the judge of all things.

Their assumption of a higher understanding is the reason they in effect demand a ‘killer’ argument—an argument so powerful it forces them to believe. But there is no such thing as a killer argument in science, and never can be. I am not one hundred percent certain that black holes are exactly what we think they are—that kind of certainty about anything doesn’t exist—but I believe black holes exist because the cumulative weight of the evidence makes belief the most reasonable response.

The evidence for black holes includes:

I do not rule out changing my mind about black holes if some new and compelling evidence were someday discovered. Until then, as long as the current evidence all points at the same explanation, that is for me a reliable indicator that the explanation is correct. If someone rejects the idea of black holes because they are too strange to wrap their minds around, I point out that the alternative involves rejecting hundreds of years of exceptionally well-tested physics, which is a far more radical, risky, and indefensible course than accepting the existence of black holes.

There has been a long history of black hole skepticism dating back to the early 20th century, which I discuss in my chapter on black holes in the forthcoming book The Story of the Cosmos (1). After this latest bout of black hole skepticism, I realized that the forces at work in the rejection of black holes are also at work when people declare themselves to be skeptical of God’s existence. The idea of God evokes in some people the same kind of reaction as black holes. Both God and black holes are unseen, mysterious, and frighteningly powerful to a degree that makes some people very uncomfortable. God is even more of a disruption to the materialistic worldview than black holes. A belief in God demands thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that some non-believers find distressing, perhaps because this group tends to be composed of people who seem to want to set themselves up as minor gods of their own universes.

This desire to assume god-like powers results in the same combination of arrogance and narcissism I have witnessed in black hole skeptics. And, just like those who reject the existence of black holes, those who reject the existence of God demand a ‘killer’ argument forcing them to believe before they will change their minds. While there can be no argument or evidence that removes all doubt in the limited human mind about anything, the arguments for God are even more compelling than the arguments for black holes.

The God of the Bible, like a good scientific theory, is the only comprehensive explanation for all of the evidence we see, such as cosmological fine tuning, human consciousness and spirituality, human morality and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. As radical as belief in the supernatural may seem to a materialist, belief in God is, in reality, the most conservative position a person can take. Just consider the radical alternatives needed to explain fine-tuning, morality, or the resurrection of Jesus in the absence of God. There are no good scientific arguments against black holes—and there is no longer a single good scientific or philosophical argument against God.

Reference

1. Salviander, S. "God, Black Holes, and the End of the Universe". In: The Story of the Cosmos: How the Heavens Declare the Glory of God. Paul M. Gould, and Daniel Ray (editors), Harvest House, Eugene OR, 2019.

Sarah Salviander is an astrophysicist who specializes in the study of quasars and supermassive black holes. Raised atheist, she converted to Christianity halfway through her doctorate. Sarah was a scientist at a large research institution for 16 years. While still active in scientific research through a small, private institute, Sarah now devotes most of her time to writing and lecturing about the relationship between science and Christianity. Sarah lives in Central Texas with her family.

Since that initial experience, I have encountered several more skeptics whose rejection of black holes is rooted in their rejection of broader modern scientific theories like big bang cosmology and the standard model of particle physics. Black holes in particular draw their ire, because, admittedly, black holes are pretty weird, and they get a lot of attention.

Though I do not completely understand their motives, I have come to better understand what these science skeptics represent. The hostility they express is a visceral reaction to being pushed past their emotional and cognitive comfort zones. They appear to be people who do not like things that are invisible. Their basic argument is never much better than “I’ll never see or touch a black hole; therefore, they don’t exist.” When presented with compelling evidence and mathematical arguments for the existence of these unseen entities, they consistently reject even the most trustworthy science on the basis that there could be alternative explanations, no matter how implausible.

Almost everyone has one of two very different worldviews based on whether or not they believe in God. Most of us become deeply invested in the worldview we’ve adopted and are inclined to be resistant to any evidence that threatens it. I suspect that most black hole skeptics, certainly the ones I have encountered, are deeply suspicious that scientists are trying to impose a false worldview on them. What that worldview is I do not quite know, but it contains a universe that is entirely material, self-evident, touchable, and understood without the help of modern scientific theories.

After attempting to discuss science with black hole skeptics, it is obvious to me that their hostility is a result of something more than just cognitive discomfort and strong emotions about what they believe. There is a profound lack of humility at work that reaches the point of arrogance and self-delusion. Black hole skeptics think they have no need to consider the evidence other people have. They believe that their intellectual superiority makes them qualified to be the judge of all things.

Their assumption of a higher understanding is the reason they in effect demand a ‘killer’ argument—an argument so powerful it forces them to believe. But there is no such thing as a killer argument in science, and never can be. I am not one hundred percent certain that black holes are exactly what we think they are—that kind of certainty about anything doesn’t exist—but I believe black holes exist because the cumulative weight of the evidence makes belief the most reasonable response.

The evidence for black holes includes:

- mathematical arguments, such as solutions to Einstein’s general relativity field equations

- observed behavior of stars and gas around invisible points of space

- explosive multi-band emission from quasars

- X-ray and radio emission from galaxy centers

- X-ray binaries

- gravitational lensing

I do not rule out changing my mind about black holes if some new and compelling evidence were someday discovered. Until then, as long as the current evidence all points at the same explanation, that is for me a reliable indicator that the explanation is correct. If someone rejects the idea of black holes because they are too strange to wrap their minds around, I point out that the alternative involves rejecting hundreds of years of exceptionally well-tested physics, which is a far more radical, risky, and indefensible course than accepting the existence of black holes.

There has been a long history of black hole skepticism dating back to the early 20th century, which I discuss in my chapter on black holes in the forthcoming book The Story of the Cosmos (1). After this latest bout of black hole skepticism, I realized that the forces at work in the rejection of black holes are also at work when people declare themselves to be skeptical of God’s existence. The idea of God evokes in some people the same kind of reaction as black holes. Both God and black holes are unseen, mysterious, and frighteningly powerful to a degree that makes some people very uncomfortable. God is even more of a disruption to the materialistic worldview than black holes. A belief in God demands thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that some non-believers find distressing, perhaps because this group tends to be composed of people who seem to want to set themselves up as minor gods of their own universes.

This desire to assume god-like powers results in the same combination of arrogance and narcissism I have witnessed in black hole skeptics. And, just like those who reject the existence of black holes, those who reject the existence of God demand a ‘killer’ argument forcing them to believe before they will change their minds. While there can be no argument or evidence that removes all doubt in the limited human mind about anything, the arguments for God are even more compelling than the arguments for black holes.

The God of the Bible, like a good scientific theory, is the only comprehensive explanation for all of the evidence we see, such as cosmological fine tuning, human consciousness and spirituality, human morality and the resurrection of Jesus Christ. As radical as belief in the supernatural may seem to a materialist, belief in God is, in reality, the most conservative position a person can take. Just consider the radical alternatives needed to explain fine-tuning, morality, or the resurrection of Jesus in the absence of God. There are no good scientific arguments against black holes—and there is no longer a single good scientific or philosophical argument against God.

Reference

1. Salviander, S. "God, Black Holes, and the End of the Universe". In: The Story of the Cosmos: How the Heavens Declare the Glory of God. Paul M. Gould, and Daniel Ray (editors), Harvest House, Eugene OR, 2019.

Sarah Salviander is an astrophysicist who specializes in the study of quasars and supermassive black holes. Raised atheist, she converted to Christianity halfway through her doctorate. Sarah was a scientist at a large research institution for 16 years. While still active in scientific research through a small, private institute, Sarah now devotes most of her time to writing and lecturing about the relationship between science and Christianity. Sarah lives in Central Texas with her family.