God and Nature Winter 2020

By Moorad Alexanian

One of most serious problems for Christian undergraduates is their exposure to new knowledge that appears to confront their Christian beliefs. The perceived conflict often undermines students’ religious faith, and in many instances drives them away from the Church. This phenomenon is typically a result of the contrast between young adults’ immature knowledge of the Christian faith and their adult knowledge of the newly acquired secular ideas.

When defending the Christian faith, it is most important to be clear on what that faith is and what it is not. Of course, the strength of our personal witness is also paramount, and we show it by “always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you” (1 Peter 3:15, NASB). In addition to Scripture, C. S. Lewis’s theological books have had a strong influence of my understanding of what Christianity is. (I recommend Mere Christianity, Miracles, The Problem of Pain, and The Screwtape Letters.) Lewis wrote in Mere Christianity:

If you are thinking of becoming a Christian, I warn you, you are embarking on something which is going to take the whole of you, brains and all. But, fortunately, it works the other way round. Anyone who is honestly trying to be a Christian will soon find his intelligence being sharpened: one of the reasons why it needs no special education to be a Christian is that Christianity is an education itself.

One of most serious problems for Christian undergraduates is their exposure to new knowledge that appears to confront their Christian beliefs. The perceived conflict often undermines students’ religious faith, and in many instances drives them away from the Church. This phenomenon is typically a result of the contrast between young adults’ immature knowledge of the Christian faith and their adult knowledge of the newly acquired secular ideas.

When defending the Christian faith, it is most important to be clear on what that faith is and what it is not. Of course, the strength of our personal witness is also paramount, and we show it by “always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you” (1 Peter 3:15, NASB). In addition to Scripture, C. S. Lewis’s theological books have had a strong influence of my understanding of what Christianity is. (I recommend Mere Christianity, Miracles, The Problem of Pain, and The Screwtape Letters.) Lewis wrote in Mere Christianity:

If you are thinking of becoming a Christian, I warn you, you are embarking on something which is going to take the whole of you, brains and all. But, fortunately, it works the other way round. Anyone who is honestly trying to be a Christian will soon find his intelligence being sharpened: one of the reasons why it needs no special education to be a Christian is that Christianity is an education itself.

"The three aspects of the whole of reality—physical, nonphysical, and supernatural—have to be considered with differing kinds of knowledge." |

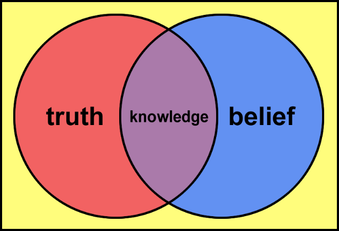

Popular discussions and debates on the purported war between science and religion, a major cause of Christians abandoning the faith, are never ending. This is because people often lack a clear conception of what kinds of knowledge need be used to understand the whole of reality, including the human experience. A good way to clarify the necessary assumptions that rational beings must make in order to carry out a rational analysis of reality is to define the subject matters of the kinds of knowledge needed.

Scripture makes it clear that humans are body, mind, and soul as created in the image of the Triune God, Creator of the Universe. Accordingly, a generous description of the whole of reality would span from the physical to the supernatural realm, with a nonphysical realm in between that would include elements of life, man, consciousness, rationality, mental and mathematical abstractions, etc.

The three aspects of the whole of reality—physical, nonphysical, and supernatural—have to be considered with differing kinds of knowledge. Each kind of knowledge has its own data and its own way of ascertaining the likely truth or falsity of any proposition inferred from the data and assumed prior information (Bayesian logic).

As a theoretical physicist, I find the theory of knowledge (epistemology) proposed by William Oliver Martin (The Order and Integration of Knowledge, The University of Michigan Press, 1957) quite appealing. Martin considers as autonomous the following kinds of knowledge: history (H), metaphysics (M), theology (T), formal logic (FL), mathematics (M), and experimental science (G), with metaphysics and theology constituting the two domains of the ontological context, and the others (H, FL, M, and G) as positive kinds of knowledge. History and experimental science are the two domains of the phenomenological context, whereas formal logic and mathematics are the domain of intentional context and formal context, respectively.

Synthetic kinds of knowledge are the integration of a positive kind of knowledge with the ontological (metaphysics and/or theology). For instance, the human or social sciences are all examples of synthetic kinds of knowledge that integrate scientific studies with the humanities, which fundamentally deal with the nature of humans. Similarly, in the philosophy of history, of mathematics, of science, or of Nature, which are synthetic kinds of knowledge, the mode or aspect studied is integrated with the mode of existence or being, which is the subject matter of metaphysics and theology.

It is in the study of unique historical events—say, in cosmological or biological evolution—where the conflict between science and religion may arise. For instance, the Christian faith is based solely on the historicity of Jesus of Nazareth—on the reality of His life, death, and resurrection. Absent those historical events, there would be no Christian faith. In fact, one may even argue that the Christian faith is not a religion, since in a religion man seeks God while in the Christian faith God sought man. The Christian faith, even if considered as a religion, has an essential historical element in its constitution in addition to the theological propositions that underlie the supernatural aspect of the faith.

It is important to emphasize that incoming Christian college students must develop the ability to do critical thinking in order to safeguard their faith from false ideologies. Michael Scriven and Richard Paul provide a useful definition of critical thinking:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action (1).

In other words, critical thinking requires a healthy brain and plenty of knowledge. Scientists, philosophers, and theologians accumulate knowledge when analyzing different aspects of reality and search for particular hypotheses or models to fit their respective subject matters. For instance, it is foolish for a scientist to require the kind of evidence that is appropriate to establish truthful statements in experimental science from a theologian who studies the intrinsic nature of God and how God interacts with His creation. The theologian has his own source of evidentiary data that differs from that of the scientist. Of course, our ultimate goal is to integrate these different kinds of knowledge into an all-encompassing worldview.

A first, reasonable, and useful definition of science is that it is the study of the physical aspect of Nature, and its subject matter is data that can be collected, in principle, by purely physical devices. This is certainly the case in physics, and to the extent that we reduce all studies of Nature to physics, which many incorrectly do, then this definition of science is fundamental. Therefore, the laws of experimental science are generalizations of historical propositions—that is, experimental data. Note that consciousness and rationality are nonphysical, since purely physical devices cannot detect them—only conscious beings can. In addition, life cannot be reduced to the purely physical. Humans have physical (body), nonphysical (mind), and supernatural (soul) aspects to their being. It is curious that human rationality and consciousness are used to know Nature and God, yet, paradoxically, humans may be unable to formulate a scientific theory either of life or of self.

Religious concepts and beliefs are based on the notion of divinity, so one must posit the existence of the supernatural, which transcends Nature but may contain all or part of it. A counterfeit expert was once asked, “How can you recognize all the ways of forging currency when there are so many of them?” The expert said, “I spend all my time looking at the real currency and can easily discern the real ones from the false ones.” We must know our Christian faith through and through so we can recognize that which is not part of it.

Therefore, my advice to incoming Christian college students is to know your faith very well. In addition, know what science is and what it is not, know your epistemology, and then you can successfully reconcile your Christian faith with science and develop a worldview that will encompass the whole of reality and thus make you wise! “But sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts, always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you, yet with gentleness and reverence” (1 Peter 3:15, NASB).

Reference

Moorad Alexanian is a physics professor at the Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography (University of North Carolina Wilmington) in Wilmington, North Carolina. He has published widely in different areas of physics, quantum field theory, cosmology, quantum optics, statistical mechanics, critical phenomena, and black holes. In addition, he has a very wide interest in the integration of science and the Christian faith.

Scripture makes it clear that humans are body, mind, and soul as created in the image of the Triune God, Creator of the Universe. Accordingly, a generous description of the whole of reality would span from the physical to the supernatural realm, with a nonphysical realm in between that would include elements of life, man, consciousness, rationality, mental and mathematical abstractions, etc.

The three aspects of the whole of reality—physical, nonphysical, and supernatural—have to be considered with differing kinds of knowledge. Each kind of knowledge has its own data and its own way of ascertaining the likely truth or falsity of any proposition inferred from the data and assumed prior information (Bayesian logic).

As a theoretical physicist, I find the theory of knowledge (epistemology) proposed by William Oliver Martin (The Order and Integration of Knowledge, The University of Michigan Press, 1957) quite appealing. Martin considers as autonomous the following kinds of knowledge: history (H), metaphysics (M), theology (T), formal logic (FL), mathematics (M), and experimental science (G), with metaphysics and theology constituting the two domains of the ontological context, and the others (H, FL, M, and G) as positive kinds of knowledge. History and experimental science are the two domains of the phenomenological context, whereas formal logic and mathematics are the domain of intentional context and formal context, respectively.

Synthetic kinds of knowledge are the integration of a positive kind of knowledge with the ontological (metaphysics and/or theology). For instance, the human or social sciences are all examples of synthetic kinds of knowledge that integrate scientific studies with the humanities, which fundamentally deal with the nature of humans. Similarly, in the philosophy of history, of mathematics, of science, or of Nature, which are synthetic kinds of knowledge, the mode or aspect studied is integrated with the mode of existence or being, which is the subject matter of metaphysics and theology.

It is in the study of unique historical events—say, in cosmological or biological evolution—where the conflict between science and religion may arise. For instance, the Christian faith is based solely on the historicity of Jesus of Nazareth—on the reality of His life, death, and resurrection. Absent those historical events, there would be no Christian faith. In fact, one may even argue that the Christian faith is not a religion, since in a religion man seeks God while in the Christian faith God sought man. The Christian faith, even if considered as a religion, has an essential historical element in its constitution in addition to the theological propositions that underlie the supernatural aspect of the faith.

It is important to emphasize that incoming Christian college students must develop the ability to do critical thinking in order to safeguard their faith from false ideologies. Michael Scriven and Richard Paul provide a useful definition of critical thinking:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action (1).

In other words, critical thinking requires a healthy brain and plenty of knowledge. Scientists, philosophers, and theologians accumulate knowledge when analyzing different aspects of reality and search for particular hypotheses or models to fit their respective subject matters. For instance, it is foolish for a scientist to require the kind of evidence that is appropriate to establish truthful statements in experimental science from a theologian who studies the intrinsic nature of God and how God interacts with His creation. The theologian has his own source of evidentiary data that differs from that of the scientist. Of course, our ultimate goal is to integrate these different kinds of knowledge into an all-encompassing worldview.

A first, reasonable, and useful definition of science is that it is the study of the physical aspect of Nature, and its subject matter is data that can be collected, in principle, by purely physical devices. This is certainly the case in physics, and to the extent that we reduce all studies of Nature to physics, which many incorrectly do, then this definition of science is fundamental. Therefore, the laws of experimental science are generalizations of historical propositions—that is, experimental data. Note that consciousness and rationality are nonphysical, since purely physical devices cannot detect them—only conscious beings can. In addition, life cannot be reduced to the purely physical. Humans have physical (body), nonphysical (mind), and supernatural (soul) aspects to their being. It is curious that human rationality and consciousness are used to know Nature and God, yet, paradoxically, humans may be unable to formulate a scientific theory either of life or of self.

Religious concepts and beliefs are based on the notion of divinity, so one must posit the existence of the supernatural, which transcends Nature but may contain all or part of it. A counterfeit expert was once asked, “How can you recognize all the ways of forging currency when there are so many of them?” The expert said, “I spend all my time looking at the real currency and can easily discern the real ones from the false ones.” We must know our Christian faith through and through so we can recognize that which is not part of it.

Therefore, my advice to incoming Christian college students is to know your faith very well. In addition, know what science is and what it is not, know your epistemology, and then you can successfully reconcile your Christian faith with science and develop a worldview that will encompass the whole of reality and thus make you wise! “But sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts, always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you, yet with gentleness and reverence” (1 Peter 3:15, NASB).

Reference

Moorad Alexanian is a physics professor at the Department of Physics and Physical Oceanography (University of North Carolina Wilmington) in Wilmington, North Carolina. He has published widely in different areas of physics, quantum field theory, cosmology, quantum optics, statistical mechanics, critical phenomena, and black holes. In addition, he has a very wide interest in the integration of science and the Christian faith.