Some Pastoral Considerations of CRISPR CAS 9 Gene EditingBy Mario A. Russo

The story that scientists have successfully edited the human genome has resurfaced several times in the media since its initial release in August of 2017. In an international collaborative effort, scientists from the U.S., South Korea, and China, corrected a genetic mutation that causes a heart defect, which has been known to lead to death in young athletes. While this news is exciting, it can also be concerning for many. Human genome editing raises all sorts of biological, ethical, and social questions. As a pastor, I want to explore some the pastoral considerations.

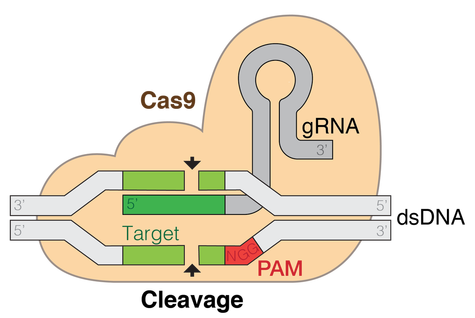

What Happened? Scientists have been working for years on trying to edit the genes of human embryos. The potential for improvements to life and health have driven scientists to find a safe and effective way to make those edits. The first week of August 2017, the announcement came: human embryo genes had been successfully edited to correct a disease-causing mutation. But what actually happened? And what does it mean? CRISPR (pronounced crisper) is an acronym for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats,” which were originally discovered in bacteria. CRISPRs contain repeating DNA sequences followed by short “spacer” sequences. The process of CRISPR gene editing is fairly “simple.” Scientists introduce a DNA cutting protein called CAS9 along with a strand of RNA that matches and targets a specific gene. Once the CAS9-RNA complex finds its target genomic location, it unwinds the DNA, binds and cuts it. The cell will naturally try to repair the cut, which often leads to a mutation at that site. [1] In a recent study using the CRISPR technique, the accuracy of targeting to the correct gene was an impressive 95%. The CRISPR technique is a remarkable and potentially revolutionary scientific development. There is Concern About Where This Could Lead As online and in-person discussions about this remarkable technology grows, it would be worth bearing in mind that not everyone may be excited about it. Some are concerned about the social and ethical implications of advancements like this. The most obvious concern is that CRISPR could be used as a precursor to eugenics: people paying to have children with enhanced traits, while others with disabilities are devalued. Their concern is not entirely illegitimate. History is full of examples of atrocities being committed by humans against other humans, as well as scientific advances with unintended consequences. It is easy to see why some people would be concerned that this scientific advance could be misused, or even become dangerous. It is important that we not dismiss this concern as invalid. In February, a National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee endorsed modifying embryos, but only to correct mutations that cause “a serious disease or condition” and when no “reasonable alternatives” exist. The question that is raised from this is, how do we define "reasonable alternatives," and determine if they already exist? There is some debate in this area, and further discussion and clarification are needed. CRISPR has Potential to Do a Lot of Good Because of this research, doors are now open for further genetic defects to be “edited.” In short, this new discovery allows for something broken to be mended. So, while the threat of abuse is still present, this new discovery has great potential to be used for good. Genetic diseases caused by mutations are not something most people think about every day. Genetic mutations cause all sorts of serious diseases and other problems: cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia, Tay-Sachs disease, and color-blindness, just to name a few. By eliminating harmful mutations in the DNA, scientists can eliminate many inheritable diseases. In this case, scientists eliminated a genetic mutation that causes a heart defect, thus prolonging life for those afflicted. CRISPR offers families with genetic diseases hope of longer and healthier lives. Moreover, proponents of CRISPR argue that this new discovery can begin making an impact on infertility. According to US News and World Report, about 12% of the US population (and roughly 7.3 million women) face infertility. R. Alta Charo (a bioethicist at University of Wisconsin at Madison), says this method of gene editing provides hope of finding answers as to what causes infertility and miscarriages. Couples who were not capable of having children may now not only be able to find out why, but fix the problem for themselves and future generations. A Few Pastoral Thoughts As a pastor, my heart wants to rejoice over the potential positive impacts CRISPR can have for people with serious diseases. I have a friend with cystic fibrosis, and when I think about how this technology can impact his life and family, it excites me. However, I also feel concern. Where can and will this technology lead us as a society? What physical effects (or side effects?) can come to patients of gene editing? What impact can it have on future generations? The mission of the Church is to follow the example of Jesus in fixing that which was broken. Jesus’ death and resurrection are all about redeeming a broken world, and ultimately “making all things new.” Genetic mutations are not the result of sin or the fall of Adam. Jesus’s death and resurrection are not about working to eliminate genetic mutations. The gospel is about God and the redemption of humankind and the whole universe. The work of these scientists, and others seemingly echoes this purpose, the redemption of the image of God in humankind. But at what cost? And what impact toward us who bear the image of God? As humans, we were created to bear the image of God in this world. In some ways, this scientific advance promotes human flourishing, and helps fulfill the original purpose of humans as image bearers. Yet, in other ways, it can seem to violate that purpose and destroy life. The Roman Catholic Church was instrumental in efforts to repeal early eugenics laws, using arguments derived from both secular/scientific and theological sources. Indeed, the ethics of gene editing today and the potential impacts on society and human life need to continue to be considered and explored, and the Church should be the leading voice in those considerations. |

Mario Anthony Russo is a pastor, writer, and church planter. With his wife Virginia and two children, he lives and works in the Rhine-Ruhr region of Germany. He holds an Interdisciplinary Bachelor of Science degree in Biology and Psychology (U. of South Carolina), a Master of Arts in Religion (RTS), and a Doctor of Ministry (Erskine College & Seminary).

During his nearly two decades of researching, writing, and speaking in the field of Science and Religion, Mario has developed a love for the interaction between science and faith, missiology, and pastoring. You can follow him on Twitter @Mario_A_Russo |