Why the Eagle Nebula Just Doesn’t Do It For MeBy Mike Clifford

Some shapely-looking knot theory Some shapely-looking knot theory

Perhaps I should start with a confession. The Eagle Nebula just doesn’t do it for me. I’ve heard a lot of talks about the awesomeness of the universe both in church and in more secular environments, but try as I might, I don’t see particular beauty in galaxies, nebulae or supernovae. Yes, I know that the Psalmist waxed lyrical about the heavens being the work of God’s fingers, but reading Psalm 8 in context, the writer contrasts the enormity of the heavens with the tininess of humans without attributing particular beauty to the sun, moon or stars. Mrs Brown’s response to Monty Python’s universe song: “Makes you feel so, sort of insignificant, doesn’t it?” isn’t a million miles (or perhaps a hundred thousand light-years) from the same sentiment.

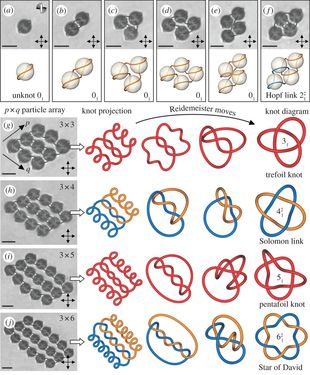

Without access to the Hubble telescope, or Google Images, the Psalmist had to rely on what he could see with his own eyes, and I’ll concede that a starry sky on a clear, warm evening with a full, harvest moon, does keep my attention for a while. But I’m just not captivated by the images from space that adorn the walls and desktops of physics students. Each to their own, I suppose. I’ve tried to understand what people see as beautiful in huge clouds of dust, hydrogen, helium and so on. If dust is so beautiful, then I have a houseful of it, which anyone is more than welcome to come and admire and even take some away with them. Maybe it’s a question of scale; I do have a lot of dust, but I admit that I can’t compete with star clusters that are tens of light years wide (yet). Then there’s the question of life “out there.” If we consider the possibility that the side-effects of galactical fireworks might have been the destruction of billions of lives on other planets, perhaps the wonder some people feel when looking at distant stars exploding might be tempered slightly. It’s like rubber-necking at a road traffic accident, or sitting back with a bowl of popcorn while the Vogons destroy the Earth in order to make way for a hyperspace bypass (see “The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy”). So, where do I see beauty? In the natural world, at length-scales down to the microscopic – I find microscopic images of dust much more beautiful than megascopic images of dust – and also in the abstract beauty of mathematics. At my secondary school, I encountered Eric Jones, a mathematics teacher. Eric was a fine, if somewhat eccentric gentleman, whose topological party piece was to take off his waistcoat without removing his suit jacket. He threatened for years to write “mathematics is pattern” on the wall of the classroom and carried out his threat just before retiring. Inspired by a love of mathematics, in my PhD studies I dabbled with chaos, fractals and the like, along with braid and knot theory. My fellow postgraduates even considered setting up in business printing T-shirts with images from our computer simulations of nonlinear equations, which were considerably easier to publish and much more lucrative than academic papers. One of my friends, Professor Sarah Hart, takes the notion of mathematics and pattern to a higher level. In her inaugural lecture https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PW5qjqcPGfY : “The Art of Group Theory and the Group Theory of Art” she considers the influence of mathematics in sacred (particularly Islamic) and secular art she explores the hypothesis that a love of symmetry, of order and a love of pattern is universal, not just for mathematicians; there is beauty there to see for everybody. At a recent conference where we considered the link between academic study and the Christian faith and how to be distinctive in our disciplines, a theoretical biochemist asked how he could apply holistic thinking to his situation. Perhaps it’s easy for physicists to see God’s fingerprints in the universe, for biologists to marvel at God’s creation in the natural world and for engineers to show God’s concern for humanity through appropriate use of technology. But for more theoretical scientists and particularly for mathematicians, the question of how to see God in our academic discipline can be trickier. I wonder, had the Psalmist paid more attention in his mathematics classes rather than daydreaming and looking out of the window at the natural world, we might have had more songs and poetry about equations – now, there’s a challenge for worship song writers. That’s not to say that math is absent from the Bible, but the God who performs “wonders without number” (Job 5:9) performs wonders with numbers too. |

Mike Clifford is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Nottingham. His research interests are in combustion, biomass briquetting, cookstove design and other appropriate technologies. He has published over 80 refereed conference and journal publications and has contributed chapters to books on composites processing and on appropriate and sustainable technologies.

Mike was recently honored by Universitas 21 (a global network of research universities) for his efforts regarding internationalisation in education both within and beyond the engineering classroom. U21 writes that "[Mike] created international experiences for students which impact positively on communities with a particular focus on Africa, but also across the globe, including Cambodia, India, Malaysia and Tajikistan." Mike has also been honored by the Higher Education Academy's Engineering Subject Centre for his innovative teaching methods involving costume, drama, poetry and storytelling. |