Why We need a third culture in churchBy John Pohl

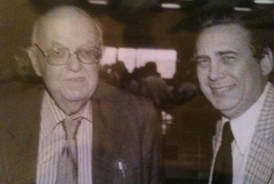

When I was a young boy in 1979, the distinguished scientist, novelist, and public speaker Baron C. P. Snow (1905-1980) visited my hometown of San Marcos, Texas (1). My parents were teaching at a small university there, which, over time, has become a large university of around 40,000 students (now called Texas State University). In the 1970s, however, the school was not big or well known, and it was somewhat unusual for a person with the stature of Snow to come to a relatively small Texas town for an academic lecture. My father, who was a military historian by training but also had a significant interest in science, had read quite a bit of Snow’s work and subsequently invited Snow to give a talk at the university (see picture at left). The topic of Snow’s lecture was “Further Observations of the Two Cultures,” based on his previous work on the two disparate cultures (in his opinion) of science and the humanities. Again, not understanding the significance of the lecture or of Snow’s history, I was oblivious when he came to our house for a dinner party and interacted with my family and my parents’ friends over the course of a couple of days. After Snow went back to England, he and my father carried on an intermittent correspondence until Snow’s death.

I believe that important things often are told to you when you are young, but such things may not influence you until you are older – which is what happened to me. Although I knew that Snow was an important writer and thinker, I essentially had no clue about the concept of the “two cultures” until my early 30s. I had just finished my medical training and so had more time to think about the relationship between science and society, as well as the relationship between science and faith. Subsequently, I read Snow’s published lecture, “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution” (2). Snow wrote many things, including a well-known fictional book series (Strangers and Brothers), but the whole idea of “The Two Cultures” was jarring and controversial in the 1950s and 1960s. “The Two Cultures” was initially presented as a Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge, but Snow subsequently published his lecture and expanded it over time. In it, he described a complete separation of two human intellectual paradigms, the “sciences” and the “humanities,” and argued that such a schism could affect civilization long term, perhaps adversely.

Some quotes from his published lecture:

When one reads through the lecture, one can see the fissure (real or perceived) that has potentially lead, in some ways, to the rise of science and to the decline of the humanities (including liberal arts, fine arts, and theology) in our culture. When arguing for more respect for the sciences, Snow did not necessarily want the humanities to decline, but he was expressing a need for a more egalitarian approach to education, encompassing both the sciences and humanities. Indeed, the perceived wall between these groups now has bled into in the current “science-faith debate,” in which we see our present culture considering the extremes of scientism and religious fundamentalism as the only valid categories to debate the issues of science and faith, without recognizing the nuances of a highly complex interaction. Later, Snow worked on an idea of a “third culture,” which would allow for improved communication between science and the humanities (3). Again, my father showed an interest here. He had given me John Brockman’s The Third Culture (4). I was in the midst of a pediatrics residency and applying for a pediatric gastroenterology fellowship, so it took me over 10 years to get around to reading this book. It is a worthwhile read. Brockman described the importance of a specific type of “third culture,” which included individuals (defined as “public intellectuals”) who could communicate deep scientific concepts to the general public. His book included essays from people such as Roger Penrose, Alan Guth, Lynn Margulis, Lee Smolin, Murray Gell-Mann, Stephen Jay Gould, and others. The essays are very good, and I highly recommend the book, as it helps a layperson’s understanding of complex scientific issues in diverse fields, including theoretical physics, evolutionary biology, and genetics. The idea of a third culture leads to the larger issue of the church in relation to scientific thought. It has been documented that young people generally have lost confidence in the Christian tradition compared to prior generations. One of the main reasons is their belief that churches are often antagonistic to science, although other reasons exist as well (5). This problem leads to a follow-up question: can we address this issue by promoting and celebrating a third culture in our churches? Indeed, I think the idea of a third culture providing a bridge between science education and faith issues in congregations would be extremely beneficial, mainly by fostering and providing improved communication for issues that are often misunderstood by the public in general, and by church laity in particular. Such third culture issues would include topics such as evolution, the age of the universe, the efficacy of vaccines, genetics, as well as many others. We already have examples of third culture authors attempting to bridge the science-faith gap in society, including Francis Collins, Katharine Hayhoe, and Denis Lamoureux. Additionally, organizations exist that are part of the third culture, such as the American Scientific Affiliation, BioLogos, and the Canadian Scientific and Christian Affiliation. However, the third culture must be cultivated and celebrated locally in our churches. I firmly believe minimal progress in this area will happen unless we provide local, open, and affirming communication regarding this issue. I can think of three areas where such open communication should be considered. Scientists attend churches, and congregations should utilize a scientist’s expertise involving the potential interactions between science and faith through sermons, Sunday school, and simple one-on-one interactions (6). Likewise, clergy and theologians certainly can be utilized to address the intersection of faith and science. Many of these people are well known (specific examples include Peter Enns or Thomas Jay Oord). It may not be feasible for such individuals to speak at local churches. However, many of them have blogs, books, and podcasts, which can be used as tools in the Sunday school and small group setting. Finally, it is essential for the laity (as well as the general public) to educate themselves on scientific issues. Indeed, if a congregation has a good understanding of science and its relation to the world (such as protecting our planet’s environment and preventing hunger and disease through public health), the promotion of a third culture can help in the understanding of God’s creation as well as to provide a moral framework for the continuing advancement of science (7). Additionally, young people may be less likely to leave a church community if there is a good baseline understanding of science in the church setting via a third culture of honest and open communication (8). The issues surrounding the “two cultures” and the development of a third culture is a clarion call, in my opinion, for the Christian to realize that it is possible and very reasonable to understand that there is no rift between his or her faith and the advances of the human scientific endeavor. The possibility of developing a third culture in our churches will help the Christian community be an important contributor to the moral, ethical, and societal issues that are constantly realized by science. Indeed, we should help the world use science in a manner similar to how our Lord commanded us: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22: 37-39). John would like to thank Robert Thoelen (fellow ASA member), Ryan Haupt, and his wife (Susan Pohl MD) for editing and providing helpful feedback. References:

|

John F. Pohl MD is a professor of pediatrics and a pediatric gastroenterologist at Primary Children’s Hospital (University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah. You can follow John at @Jfpohl on Twitter.

|