God and Nature Fall 2020

By John F. Pohl

What has been called “the hard problem of consciousness” may be one of the most difficult issues to solve scientifically, philosophically, and theologically (1). Traditionally, there are two general ways to think about how consciousness may work: dualism and materialism.

Dualism (made famous by René Descartes) provides a framework in which the mind is non-physical, while the body and brain are physical. Descartes thought that the interaction between the two occurred through the pineal gland, which we now know is not accurate. There are other, more modern ideas that describe the interaction of mind and matter, such as the theory of qualia (qualitative consciousness) (2, 3). Materialism is the idea that all conscious events in our life are based on matter (neurons, neurotransmitters, etc.), and there is nothing more involved (4).

What has been called “the hard problem of consciousness” may be one of the most difficult issues to solve scientifically, philosophically, and theologically (1). Traditionally, there are two general ways to think about how consciousness may work: dualism and materialism.

Dualism (made famous by René Descartes) provides a framework in which the mind is non-physical, while the body and brain are physical. Descartes thought that the interaction between the two occurred through the pineal gland, which we now know is not accurate. There are other, more modern ideas that describe the interaction of mind and matter, such as the theory of qualia (qualitative consciousness) (2, 3). Materialism is the idea that all conscious events in our life are based on matter (neurons, neurotransmitters, etc.), and there is nothing more involved (4).

"...the potential interaction of the microbiome with our consciousness suggests the presence of panpsychism..." |

Both frameworks, although intriguing, have issues. Can we prove that the body and mind are truly separate—that the mind can exist separate from physical reality? Alternatively, can we prove that our daily subjective experiences (for example, the feeling of love, or a reaction to hearing Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos or to seeing a Jackson Pollock painting) are just the result of atoms and molecules interacting?

Thus, we have to consider other possibilities. Panpsychism is a philosophical framework originally developed in ancient Greece that re-emerged during the latter part of the 20th century, as recently described in detail by Philip Goff (5). It has been promoted by people with different views of reality, such as Bertrand Russell from an atheist perspective and Arthur Eddington from the Quaker tradition.

Simply put, panpsychism is the theory that all entities have some degree of consciousness, and consciousness is ubiquitous. Besides humans and other mammals, “simpler” forms of life may experience consciousness as well. Lizards, birds, insects, protozoa, bacteria, and viruses could have consciousness at more primitive levels that we do not comprehend.

Broken down even further, molecules and atoms could have some degree of consciousness in very, very simplistic terms. As simple units of consciousness come together, perhaps consciousness becomes more “up-regulated” to a point that complex conscious thoughts (deciding what clothes to wear, cooking a meal, mathematics, theoretical physics, etc.) and subjectivity in thought (sensation of the color red, emotions, reaction to music or a painting, etc.) occur. Each individual component of conscious experience is described as “specific” and “unified” with the other individual components of the experience in what is known as Integrated Information Theory (IIT) (6).

Can we see evidence of panpsychism in nature? There is a case to be made for the potential of panpsychism occurring in the human microbiome, defined as the myriad of microscopic organisms (viruses, archaebacteria, prokaryotes, fungi, protists, and other eukaryotes) that live inside and on our bodies.

By living both inside and outside of the body, these microorganisms connect us to our environment. Some, such as the bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli), can be consumed through water, food, or other sources (7). In fact, over 1000 bacterial species have been described in the human intestinal tract (in addition to protozoa, fungi, and viruses), and these bacteria interact with each other to help with human digestion, intestinal wall integrity, vitamin production, and immune function (8, 9). Such processes are vital for human brain function, as digestion of food with good nutritional value is involved with prevention of neuron inflammation and improved brain activity. Conversely, obesity is associated with a disrupted intestinal microbiome, which can cause neuronal inflammation in the brain, potentially affecting cognitive ability long term (10, 11).

Is it possible that gut bacteria have an even more essential role? I would propose that the microbiome interacts with the environment and affects human health and mental processes in a manner far more complicated than is often considered, and this interplay could be considered a form of panpsychism. For example, E. coli has the ability to survive outside an organism for a prolonged period of time, which increases the risk of human gut exposure (12). Recent research has demonstrated that gut bacteria from the environment interact with the intestine to cause colonic nerves to grow in adult mice through mechanisms that are not well defined (13). Data suggest that alterations in the intestinal microbiome can lead to changes in the lungs in conditions such as asthma and cystic fibrosis (14). Cystic fibrosis, in particular, seems to be associated with some degree of “cross talk” between intestinal bacteria and lung bacteria, and the presence of pathologic bacteria in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis may be reduced by providing appropriate caloric intake that affects the composition of gut bacteria (15, 16).

Thus, we should consider if there are microbiome factors that affect humans from a mental and behavioral perspective. Such research is difficult to perform, but animal models do suggest that intestinal microbiome changes may be associated with behavioral changes, including anxiety and depression (17, 18). In humans, intestinal microbiome changes are associated with depression, although the effect of anti-depressant therapy on the microbiome is not clear-cut (19, 20, 21). Dementia, as seen in Alzheimer’s disease, also appears to be associated with microbiome changes in the mouth and intestine (22, 23). Preventative lifestyle measures, such as sleep hygiene and consuming a healthy, balanced diet, can restore the microbiome with an increase of specific bacteria that are associated with lower inflammatory effects and prevention of neurologic disease (24, 25, 26).

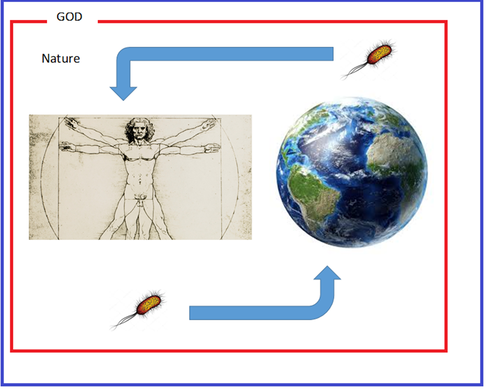

What does all this mean theologically? The possibility of a Christian perspective on panpsychism via the mechanisms of the microbiome may seem difficult to address, but theological aspects of the microbiome have been explored by others, and the microbiome should be strongly considered to be participatory if we agree that we worship a relational God. (27, 28; see Figure). The whole of microbial life has the opportunity to interact with us (29, 30). Our bodies constantly interact with the environment via the mouth, nose, skin, gut, and lungs. Once ingested or inhaled, the microbiome may have effects on consciousness in complex, holistic ways. I would hypothesize that the potential interaction of the microbiome with our consciousness suggests the presence of panpsychism, with simpler organisms providing perspectives about the environment by modifying how we are conscious about the environment.

Thus, we have to consider other possibilities. Panpsychism is a philosophical framework originally developed in ancient Greece that re-emerged during the latter part of the 20th century, as recently described in detail by Philip Goff (5). It has been promoted by people with different views of reality, such as Bertrand Russell from an atheist perspective and Arthur Eddington from the Quaker tradition.

Simply put, panpsychism is the theory that all entities have some degree of consciousness, and consciousness is ubiquitous. Besides humans and other mammals, “simpler” forms of life may experience consciousness as well. Lizards, birds, insects, protozoa, bacteria, and viruses could have consciousness at more primitive levels that we do not comprehend.

Broken down even further, molecules and atoms could have some degree of consciousness in very, very simplistic terms. As simple units of consciousness come together, perhaps consciousness becomes more “up-regulated” to a point that complex conscious thoughts (deciding what clothes to wear, cooking a meal, mathematics, theoretical physics, etc.) and subjectivity in thought (sensation of the color red, emotions, reaction to music or a painting, etc.) occur. Each individual component of conscious experience is described as “specific” and “unified” with the other individual components of the experience in what is known as Integrated Information Theory (IIT) (6).

Can we see evidence of panpsychism in nature? There is a case to be made for the potential of panpsychism occurring in the human microbiome, defined as the myriad of microscopic organisms (viruses, archaebacteria, prokaryotes, fungi, protists, and other eukaryotes) that live inside and on our bodies.

By living both inside and outside of the body, these microorganisms connect us to our environment. Some, such as the bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli), can be consumed through water, food, or other sources (7). In fact, over 1000 bacterial species have been described in the human intestinal tract (in addition to protozoa, fungi, and viruses), and these bacteria interact with each other to help with human digestion, intestinal wall integrity, vitamin production, and immune function (8, 9). Such processes are vital for human brain function, as digestion of food with good nutritional value is involved with prevention of neuron inflammation and improved brain activity. Conversely, obesity is associated with a disrupted intestinal microbiome, which can cause neuronal inflammation in the brain, potentially affecting cognitive ability long term (10, 11).

Is it possible that gut bacteria have an even more essential role? I would propose that the microbiome interacts with the environment and affects human health and mental processes in a manner far more complicated than is often considered, and this interplay could be considered a form of panpsychism. For example, E. coli has the ability to survive outside an organism for a prolonged period of time, which increases the risk of human gut exposure (12). Recent research has demonstrated that gut bacteria from the environment interact with the intestine to cause colonic nerves to grow in adult mice through mechanisms that are not well defined (13). Data suggest that alterations in the intestinal microbiome can lead to changes in the lungs in conditions such as asthma and cystic fibrosis (14). Cystic fibrosis, in particular, seems to be associated with some degree of “cross talk” between intestinal bacteria and lung bacteria, and the presence of pathologic bacteria in the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis may be reduced by providing appropriate caloric intake that affects the composition of gut bacteria (15, 16).

Thus, we should consider if there are microbiome factors that affect humans from a mental and behavioral perspective. Such research is difficult to perform, but animal models do suggest that intestinal microbiome changes may be associated with behavioral changes, including anxiety and depression (17, 18). In humans, intestinal microbiome changes are associated with depression, although the effect of anti-depressant therapy on the microbiome is not clear-cut (19, 20, 21). Dementia, as seen in Alzheimer’s disease, also appears to be associated with microbiome changes in the mouth and intestine (22, 23). Preventative lifestyle measures, such as sleep hygiene and consuming a healthy, balanced diet, can restore the microbiome with an increase of specific bacteria that are associated with lower inflammatory effects and prevention of neurologic disease (24, 25, 26).

What does all this mean theologically? The possibility of a Christian perspective on panpsychism via the mechanisms of the microbiome may seem difficult to address, but theological aspects of the microbiome have been explored by others, and the microbiome should be strongly considered to be participatory if we agree that we worship a relational God. (27, 28; see Figure). The whole of microbial life has the opportunity to interact with us (29, 30). Our bodies constantly interact with the environment via the mouth, nose, skin, gut, and lungs. Once ingested or inhaled, the microbiome may have effects on consciousness in complex, holistic ways. I would hypothesize that the potential interaction of the microbiome with our consciousness suggests the presence of panpsychism, with simpler organisms providing perspectives about the environment by modifying how we are conscious about the environment.

A Theological Model of panpsychism involving the microbiome. The microbiome comes into contact with our body via interactions with the environment. Bacteria (E. coli in this illustration) enter our body (as portrayed by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man), stay/interact with our body, and leave our body only then to re-enter the environment. The red square is all of nature that interacts with us/through us via the vehicle of the microbiome. God (illustrated as a blue square) is so much more than nature and breaks into nature (see the disruption of the red square) to interact with Creation as evidenced through Jesus Christ. |

From a religious perspective, I would further hypothesize that the presence of God inside/throughout/outside our bodies (as well as God’s interaction with our planet and the rest of the universe) breaks through the barrier of nature and interacts with all of us in ways that our microbiome helps us realize. Such an interaction has leanings of panentheism, which certainly may be true as well; however, it is interesting to consider that our interaction with the microbiome may be a consciousness-extending event reminding us of God and the importance of Creation.

What does the Bible have to say about this? There are of course no passages that name the microbiome, but Jesus did say, “I have given them the glory You gave me, so that they may be one as we are one—I in them and You in me—that they may be perfectly united, so that the world may know that You sent me and have loved them just as You have loved me” (John 17: 22-23). Could this suggest that Jesus entering Creation during his time on earth allowed Him to also take part in the effects of the microbiome? After all, the Gospels describe that he interacted by touching, eating, and drinking, which suggests the possibility that God experienced his Creation with us, and in us. Additionally, in Matthew 15: 17-20, Jesus said, “‘Do you not yet realize that whatever enters the mouth goes into the stomach and then is eliminated? But the things that come out of the mouth come from the heart, and these things defile a man. For out of the heart come evil thoughts, murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, and slander. These are what defile a man, but eating with unwashed hands does not defile him.’” In other words, the microbiome is separate from sin, as the microbiome is not defiled, and indeed, the microbiome could be one of God’s ways of providing our species with health, intelligence, consciousness, and an ability to know Him.

There is much medical, basic science, microbiology, philosophical, and indeed theological research and thought needed regarding the function of the microbiome, but it does potentially show us another way in which Christ is the “Author of Life” (Acts 3:15). The microbiome may be pointing our consciousness to a better realization of God.

References:

1. Chalmers D. Facing up to the problem of consciousness. J Conscious Stud. 1995; 2: 200-219.

2. Maung H. Dualism and its place in the philosophical structure for psychiatry. Med Health Care Philos. 2019; 22: 59-69.

3. Loorits K. Structural qualia: a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 237.

4. Hesslow G. Will neuroscience explain consciousness? J Theor Biol. 1994; 171: 29-39.

5. Goff, Philip. Galileo's Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness. New York, Pantheon, 2019.

6. Oizumi M, Albantakis L, Tononi G, et al. From the phenomenology to the mechanisms of consciousness: integrated information theory 3.0. PloS Comput Biol. 2015; 10(5): e1003588.

7. Dirk van Elsas J, Semenov A, Costa R, et al. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. ISME J. 2011; 5: 173-183.

8. Sankar S, Lagier J, Pontarotti P, et al. The human gut microbiome, a taxonomic conundrum. Syst Appl Microbiology. 2015; 38: 276-286.

9. Zhang Y, Li S, Gan R, et al. Impacts on gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16: 7493-7519.

10. Spencer S, Korosi A, Layé S, et al. Food for thought: How nutrition impacts cognition and emotion. NPJ Sci Food. 2017; 1: 7.

11. Ley R. Obesity and the human microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010; 26: 5-11.

12. Van Elsas J, Semenov A, Costa R, et al. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. ISME J. 2011; 5: 173-183.

13. Yarandi S, Kulkarni S, Saha M, et al. Intestinal bacteria maintain adult enteric nervous sytem and nitrertic neurons via toll-like receptor 2-induced neurogenesis in mice. Gastroenterol. 2020; 159: 200-213.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.050.

14. Chunxi L, Haiyue L, Yanxia L, et al. The gut microbiota and respiratory disease: new evidence. J Immunol Res. 2020; 2020: 2340670.

15. Madan J, Koestler D, Stanton B, et al. Serial analysis of the gut and respiratory microbiome in cystic fibrosis in infancy: interaction between intestinal and respiratory tracts and impact of nutritional exposures. mBio. 2012; 3: e00251-12.

16. Anand S and Mande S. Diet, microbiota, and gut-lung connection. Front Microbiol. 2018; 9: 2147.

17. Salvo E, Stokes P, Keogh C, et al. A murine model of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease causes microbiota-gut-brain axis deficits in adulthood. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020; doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00177.2020. Online ahead of print.

18. Zhao Z, Wang B, Mu L, et al. Long-term exposure to ceftriaxone sodium induces alternation of gut microbiota accompanied by abnormal behaviors in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020; doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00258. eCollection 2020.

19. Rudzki L and Maes M. The microbiota-gut-immune-glia (MGIG) axis in major depression. Mol Neurobiol. 2020; doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01961-y. Online ahead of print.

20. Halverson T and Alagiakrishnam K. Gut microbes in neurocognitive and mental health disorders. Ann Med. 2020; doi: 10.1080/07853890.2020.1808239. Online ahead of print.

21. Liskiewicz P, Kaczmarczyk M, Misiak B. Analysis of gut microbiota and intestinal integrity markers of inpatients with major depressive disorder. Prog neuropsychopharmacol biol psychiatry. 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110076. Online ahead of print.

22. Bathini P, Foucras S, Dupanloup I, et al. Classifying dementia progression using microbial profiling of saliva. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020; doi: 10.1002/dad2.12000. eCollection 2020.

23. Bulgart H, Neczypor E, Wold L, et al. Microbial involvement in Alzheimer disease development and progression. Mol Neurodegener. 2020; 15: 42.

24. Grosicki G, Riemann B, Flatt A, et al. Self-reported sleep quality is associated with gut microbiome composition in young, healthy individuals: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2020; 73: 76-81.

25. Jung Y, Tagele S, Son H, et al. Modulation of gut microbiota in Korean navy trainees following a healthy lifestyle change. Microorganisms. 2020; 8: E1265.

26. Vogt N, Kerby R, Dill-McFarland K, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 13537.

27. Carlson C. You are plural. Christianity Today. 2016; 9: 60-63.

28. Kunnen M and Carlson C. Connected to God’s Good World, the Human Microbiome. Christian Scholar’s Review. 2017; 46: 113-126.

29. Carding S, Davis, N, Hoyles L. Review article: the human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46: 800-815.

30. Nash A, Auchtung T, Wong M, et al. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome. 2017; 5: 153.

Bible quotes are from the Berean Study Bible.

John F. Pohl MD is a professor of pediatrics and a pediatric gastroenterologist at Primary Children’s Hospital (University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah. You can follow John at @Jfpohl on Twitter.

What does the Bible have to say about this? There are of course no passages that name the microbiome, but Jesus did say, “I have given them the glory You gave me, so that they may be one as we are one—I in them and You in me—that they may be perfectly united, so that the world may know that You sent me and have loved them just as You have loved me” (John 17: 22-23). Could this suggest that Jesus entering Creation during his time on earth allowed Him to also take part in the effects of the microbiome? After all, the Gospels describe that he interacted by touching, eating, and drinking, which suggests the possibility that God experienced his Creation with us, and in us. Additionally, in Matthew 15: 17-20, Jesus said, “‘Do you not yet realize that whatever enters the mouth goes into the stomach and then is eliminated? But the things that come out of the mouth come from the heart, and these things defile a man. For out of the heart come evil thoughts, murder, adultery, sexual immorality, theft, false testimony, and slander. These are what defile a man, but eating with unwashed hands does not defile him.’” In other words, the microbiome is separate from sin, as the microbiome is not defiled, and indeed, the microbiome could be one of God’s ways of providing our species with health, intelligence, consciousness, and an ability to know Him.

There is much medical, basic science, microbiology, philosophical, and indeed theological research and thought needed regarding the function of the microbiome, but it does potentially show us another way in which Christ is the “Author of Life” (Acts 3:15). The microbiome may be pointing our consciousness to a better realization of God.

References:

1. Chalmers D. Facing up to the problem of consciousness. J Conscious Stud. 1995; 2: 200-219.

2. Maung H. Dualism and its place in the philosophical structure for psychiatry. Med Health Care Philos. 2019; 22: 59-69.

3. Loorits K. Structural qualia: a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 237.

4. Hesslow G. Will neuroscience explain consciousness? J Theor Biol. 1994; 171: 29-39.

5. Goff, Philip. Galileo's Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness. New York, Pantheon, 2019.

6. Oizumi M, Albantakis L, Tononi G, et al. From the phenomenology to the mechanisms of consciousness: integrated information theory 3.0. PloS Comput Biol. 2015; 10(5): e1003588.

7. Dirk van Elsas J, Semenov A, Costa R, et al. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. ISME J. 2011; 5: 173-183.

8. Sankar S, Lagier J, Pontarotti P, et al. The human gut microbiome, a taxonomic conundrum. Syst Appl Microbiology. 2015; 38: 276-286.

9. Zhang Y, Li S, Gan R, et al. Impacts on gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015; 16: 7493-7519.

10. Spencer S, Korosi A, Layé S, et al. Food for thought: How nutrition impacts cognition and emotion. NPJ Sci Food. 2017; 1: 7.

11. Ley R. Obesity and the human microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010; 26: 5-11.

12. Van Elsas J, Semenov A, Costa R, et al. Survival of Escherichia coli in the environment: fundamental and public health aspects. ISME J. 2011; 5: 173-183.

13. Yarandi S, Kulkarni S, Saha M, et al. Intestinal bacteria maintain adult enteric nervous sytem and nitrertic neurons via toll-like receptor 2-induced neurogenesis in mice. Gastroenterol. 2020; 159: 200-213.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.050.

14. Chunxi L, Haiyue L, Yanxia L, et al. The gut microbiota and respiratory disease: new evidence. J Immunol Res. 2020; 2020: 2340670.

15. Madan J, Koestler D, Stanton B, et al. Serial analysis of the gut and respiratory microbiome in cystic fibrosis in infancy: interaction between intestinal and respiratory tracts and impact of nutritional exposures. mBio. 2012; 3: e00251-12.

16. Anand S and Mande S. Diet, microbiota, and gut-lung connection. Front Microbiol. 2018; 9: 2147.

17. Salvo E, Stokes P, Keogh C, et al. A murine model of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease causes microbiota-gut-brain axis deficits in adulthood. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2020; doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00177.2020. Online ahead of print.

18. Zhao Z, Wang B, Mu L, et al. Long-term exposure to ceftriaxone sodium induces alternation of gut microbiota accompanied by abnormal behaviors in mice. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020; doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00258. eCollection 2020.

19. Rudzki L and Maes M. The microbiota-gut-immune-glia (MGIG) axis in major depression. Mol Neurobiol. 2020; doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-01961-y. Online ahead of print.

20. Halverson T and Alagiakrishnam K. Gut microbes in neurocognitive and mental health disorders. Ann Med. 2020; doi: 10.1080/07853890.2020.1808239. Online ahead of print.

21. Liskiewicz P, Kaczmarczyk M, Misiak B. Analysis of gut microbiota and intestinal integrity markers of inpatients with major depressive disorder. Prog neuropsychopharmacol biol psychiatry. 2020; doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110076. Online ahead of print.

22. Bathini P, Foucras S, Dupanloup I, et al. Classifying dementia progression using microbial profiling of saliva. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020; doi: 10.1002/dad2.12000. eCollection 2020.

23. Bulgart H, Neczypor E, Wold L, et al. Microbial involvement in Alzheimer disease development and progression. Mol Neurodegener. 2020; 15: 42.

24. Grosicki G, Riemann B, Flatt A, et al. Self-reported sleep quality is associated with gut microbiome composition in young, healthy individuals: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2020; 73: 76-81.

25. Jung Y, Tagele S, Son H, et al. Modulation of gut microbiota in Korean navy trainees following a healthy lifestyle change. Microorganisms. 2020; 8: E1265.

26. Vogt N, Kerby R, Dill-McFarland K, et al. Gut microbiome alterations in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 13537.

27. Carlson C. You are plural. Christianity Today. 2016; 9: 60-63.

28. Kunnen M and Carlson C. Connected to God’s Good World, the Human Microbiome. Christian Scholar’s Review. 2017; 46: 113-126.

29. Carding S, Davis, N, Hoyles L. Review article: the human intestinal virome in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017; 46: 800-815.

30. Nash A, Auchtung T, Wong M, et al. The gut mycobiome of the Human Microbiome Project healthy cohort. Microbiome. 2017; 5: 153.

Bible quotes are from the Berean Study Bible.

John F. Pohl MD is a professor of pediatrics and a pediatric gastroenterologist at Primary Children’s Hospital (University of Utah) in Salt Lake City, Utah. You can follow John at @Jfpohl on Twitter.