Spare Parts

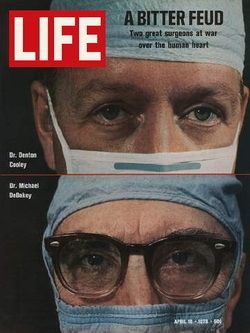

by Walt Hearn

"One Piece at a Time" was a funny ballad sung by Johnny Cash in the 1970s. It told the story of a Kentucky hillbilly working on a Cadillac assembly line in Detroit. When he realized he'd never be able to buy one of the luxury cars he was putting together, he started swiping parts from the factory to build his own. It took him years, but the parts didn't fit together well because the models had kept changing. I think of that song whenever I review my personal medical history. I've had a number of extraneous parts attached to my body over many years by different highly skilled mechanics. Take my two front teeth, for example. When I was a kid growing up in Houston, Texas, in the 1930s, we used to play "bicycle polo" in the middle of our street, using mallets and a big wooden ball from a croquet set. On Sunday afternoons we could easily dodge the cars because there wasn't much traffic. What I failed to dodge one Sunday was a hard-hit croquet ball sailing through the air. It caught me smack in the mouth, breaking off one of my upper incisors and ending the polo match. Neighborhood kids managed to disentangle me from my fallen steed and walk me home. By that time I was screaming in pain from the exposed nerve in the pulp hanging down from the break. My father was out of town. My mother tried to calm me down but was in a nervous tizzy herself. She started calling dentists listed alphabetically in the Yellow Pages, getting to the "C"s before she found one willing to open his office for us on a Sunday. That was the beginning of what became many hours in a dentist's chair for me. That afternoon, Dr. Cooley numbed my gums and extracted what was left of the tooth. In subsequent appointments he ground down the tooth next to the broken one to a pin and built a two-tooth cap mounted on that pin. Incidentally (or dentally?), my accident contributed to cardiovascular research―by helping to put Dr. Cooley's son through medical school. By the 1950s, when I was on the biochemistry faculty at Baylor Med in Houston, the son, Denton Cooley, was a professor of surgery doing artificial heart research with the famous heart surgeon Michael DeBakey. They later became bitter rivals after Cooley kept a guy alive in 1969 with an early artificial heart until he could do a donor heart transplant. The patient died of an infection. Cooley was censured for using a still-experimental device on a patient. I'm not sure what lay behind their rift, but I've heard that the two researchers reconciled before DeBakey died in 2008. My two-teeth-on-a-single-root cap lasted forty-plus years despite being knocked out repeatedly in pick-up basketball games and Navy boxing matches. It became less and less secure. Finally, just before leaving academia in 1972, I took advantage of Iowa State University's comprehensive faculty health insurance: I had that gadget replaced by a removable two-tooth partial denture, anchored to some sturdy molars. That piece of hardware has been "part and partial" of my body for another forty years. I was a full-grown adult before I had to have eyeglasses for reading. Ten or fifteen years ago a hearing aid was added to my equipment. Now I say that I carry my "eyes" in one pocket and my "ears" in another. I'm totally dependent on all these spare parts and especially on the most recent (and way most expensive) one, an ICD ("Implanted Cardioverter Device")―not to be confused with the IED ("Improvised Explosive Device") so deadly to U.S. soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. After sleeping through a heart attack in 1989, I've functioned pretty well with only two-thirds of my heart still beating, but in 1994 I had to have quadruple bypass surgery. Today bypass surgery is a high-tech operation done through small incisions, but the old-fashioned kind required splitting my sternum and then wiring it back together again. (My three-inch scar reminds me of those Z-shaped scars left by "the sword of Zorro" in old westerns; thankfully, the open-heart surgeon who carved his initial on my chest was named Iverson.) Out walking in 2010, I felt strong heart beats but by the time I got to the doctor's office, I had no pulse. Then things got hazy. In the emergency room I remember looking up at the grim face of my cardiologist. He was holding those paddles you see in TV's "ER" to start my heart beating again. I woke up a week later with an ICD implanted on the left side of my chest. This modern battery-operated device has electrical leads going into my heart. At low pulse rates it acts like a pacemaker. If my heart starts beating really fast (as in the ventricular fibrillation that almost killed me), it's supposed to send a high-voltage jolt to shock my heart into behaving itself. The complexity of such a small gadget amazes me. It continually transmits an EKG ("electrocardiogram") to a monitor on my desk attached to our phone line, so a cardiologist merely has to dial a phone number to read the tracing. The ICD keeps track of when its battery will need replacing (about seven years from now). It keeps me alive and continually thanking God for Boston Scientific (its manufacturer) and for Cardiovascular Consultants of Oakland (the medical team that monitors my monitor). While gaining all these attachments, I've also lost some of my original equipment. The first to go (not counting circumcision) were my tonsils and adenoids. In the pre-antibiotic era in which I grew up, kids who kept getting throat infections had their tonsils removed as a matter of course. I recall a rather painful recovery, but something else happened, too. Pediatric surgery transformed me from a scrawny kid into a pudgy kid. The preoperative fasting was probably my first experience of hunger, and I didn't like it one bit. Since then I've been on a "seafood diet." That is, when I see food, I want to eat it. Toward the end of my first year in grad school I had an episode of abdominal pain. The doctor told me to keep a record of what I ate to see what had caused it. In a day or so I had a more violent attack and my skin turned yellow. The doctor was embarrassed that he hadn't thought of gallstones as a cause, but after all, he said, I wasn't "fat, female, forty, or fertile." My cholecystectomy was again the old-fashioned kind, leaving an eight-inch vertical scar on my abdomen. Through that huge incision I think the surgeon grabbed my appendix, too. He may have thought of reaching up from inside for my tonsils, but of course they were already out. I didn't mean for this column to turn into an "organ concert," but the Affordable Care Act has been on my mind, reminding me to thank God both for dedicated medical practitioners and for adequate medical insurance. After I switched from a tenured academic position to a tenuous free-lance editing career, my wife and I had to get along without medical insurance for over 15 years. Along the way we experienced two major miracles of God's timing. For a few of those years we were editing an encyclopedia. (I sometimes say that I know everything between "A" and "E," at which point the project was dropped.) Although Ginny was the more experienced editor and we shared the work equally, the publisher put me on his full-time payroll under my name alone. That arrangement provided benefits we wouldn't have had with two part-time jobs. When Ginny needed surgery in 1979, it was covered by "my" insurance and didn't cost us a thing. After that, it was back to square one, without health insurance. Worried about our lack of insurance, Ginny eventually took a full-time job, which proved so unsatisfactory that she quit after only three weeks. She could have continued our medical coverage under COBRA (Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985), if we could have afforded it. But guess what? During that three weeks in 1989, her insurance covered my heart attack! By 1991 I was on Medicare, and with our Social Security income we could also afford a "Medigap" policy from AARP (American Association of Retired Persons). So by 2010, when I needed three weeks in the hospital and this ultra-high-tech ICD, we were all set. A few weeks before, Ginny had spent over a week in the same hospital for a hip replacement. We managed to escape infection―and bankruptcy. Today our continuing medical bills are divided between Medicare, AARP, and us in a way too complicated for me to figure out, but I know that without insurance in 2010 we would have had to come up with hundreds of thousands of dollars. AARP, probably thinking it would be cheaper to keep us healthy, has now given us free "Silver Sneakers" memberships in a nearby fitness gym, where we try to "work out" three or four times a week. So far I haven't fallen off any of the equipment. I probably still get most of my exercise by jumping to conclusions. Despite being patched up a few times, in biblical terms I've reached my "four score"―plus "eight more." Yet Ginny and I are still together, still vertical, reasonably mobile, and occasionally lucid. Can't beat that, at my age. Who needs a Cadillac? Praising God, you know, is a pretty good exercise, too. |