Quantum Mechanics and the Question of Divine Knowledge

by Stephen J. Robinson

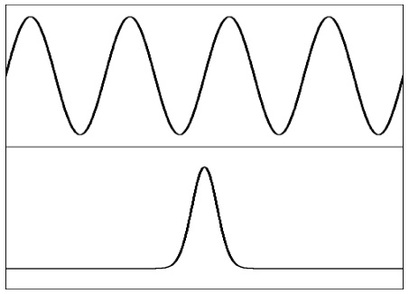

Figure 1. (top) The wave function of a particle with a well-defined momentum. (bottom) The wave function of a particle with a well-defined position. Figure 1. (top) The wave function of a particle with a well-defined momentum. (bottom) The wave function of a particle with a well-defined position.

Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 contains the following dialogue (with omissions for brevity) between Yossarian, an American bombardier in World War II who wishes to be removed from combat, and his doctor, Doc Daneeka.

Yossarian: Can’t you ground someone who’s crazy? Doc Daneeka: Oh, sure. I have to. There’s a rule saying I have to ground anyone who’s crazy. Yossarian: Then why don’t you ground me? I’m crazy. Doc Daneeka: Anyone who wants to get out of combat duty isn’t really crazy. Heller continues: “A concern for one’s safety in the face of dangers that [are] real and immediate [is] the process of a rational mind.” Assuming one cannot be crazy and not crazy at the same time, if a soldier really were “crazy” and asked to be grounded because of his condition, then he just spoke a completely reasonable statement and thus contradicted himself. Now consider the following conundrum: “Is the answer to this question, ‘No’?” If you answer “yes,” you are stating that the answer is indeed “no,” but you just stated the opposite, and vice versa for an answer of “no.” Or perhaps you’ve heard something along the lines of “Have you stopped cheating on your taxes yet?” “Yes” or “no” is not a very comfortable answer if the asker is an IRS agent. These problems extend into the tangible world as well, such as in the lottery paradox:[1] it is correct for each person to think that his lottery ticket won’t win, but it is incorrect to think that someone won’t win. These types of contradictions and paradoxes lead to a troubling conclusion for any determinist: basic irrationalities and contradictions we create in our minds must be derived from a set of (assumedly) comprehensive, coherent, rational, immutable set of physical laws. More troubling still, if every thought we have is simply due to the transfer of chemicals from one part of our brains to another, then our very thoughts must obey physical laws.[2] But if our thoughts are merely chemical processes, how can we have any confidence in the very laws we formulate to describe those chemical processes?[3] To paraphrase Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart,[4] I may not know how to prove an idea absurd, but I know an absurd idea when I see it. This line of reasoning leads many (including myself) to conclude that there must be a nonphysical disconnect between mind (or soul) and body, known as Cartesian dualism.[5] That is, to think is quite different than to be. How do we account for this dichotomy of mind and brain? For a Christian, the answer may be simple: God, perhaps with his big Sistine Chapel finger, or perhaps through an extended period of evolution through natural selection, has implanted sentient abilities in us, including the ability to have thoughts contrary to the laws of physics. But would such a dichotomy apply to God? Can God “understand” irrationalities and contradictions? Does God really know everything? This article hopes to address some of those questions in the light of Christian tradition and modern science. What is Omniscience? The word omniscience can be dissected into the Latin omnis, “all,” and scire, “to know.” About a thousand years ago, theologian Anselm of Canterbury defined God as “something of which nothing greater can be thought.”[6] From a power perspective, this would imply omnipotence; from domain, omnipresence; from goodness, omnibenevolence; from knowledge, omniscience. The same sorts of arguments that apply to the latter apply to the former three,[7] so we’ll leave them out of the discussion. (These arguments also apply to the omniscience of teenagers, but we’ll also leave them out.) The Bible does make a few direct claims about God’s omniscience (e.g., Psalm 147:5b, Job 37:16b). However, it could be argued that the context thereof places those statements in the same realm as the Bible’s other claims of God’s knowledge, in that they are only comparisons to human ignorance: for example, God knows our secrets (Psalm 44:21), the end of times (Matthew 24:36), how to correctly judge situations (1 Samuel 2:3), etc. We then generally owe our beliefs about omniscience to the work of theologians[8] or, at the very least, to the argument that Biblical allusions to God’s knowledge of every possible domain (e.g., heavens, earth, past, present, future, etc.) create a piecemeal omniscience;[9] I’m not here to dispute either. Instead, the focus will be on reconciling God’s assumed omniscience with our own understandings of science, especially quantum science. Granted, this endeavor may be similar to a dog trying to understand why its tail is so elusive, but an effort may be beneficial nonetheless. What is Rationality? Rationality is a notoriously difficult term to define; since rationality and reason are often cited as fundamental differences between humans and animals, what we usually mean by these terms is “how humans think.”[10] Merriam-Webster defines rational as “having reason or understanding” and reason as “the power of comprehending, inferring, or thinking especially in orderly rational ways.” As we must hand-wave past circular definitions, we could agree that a rational person “makes sense” to most people. Extending this beyond what we are, we may say that, for example, a rational argument follows rules of logic, a rational universe is predictable, or a rational God creates order. Consider our physical laws. We expect that if we put one million Isaac Newtons (think of the productivity!) under one million apple trees with the same initial conditions, every apple would fall simultaneously with the same trajectory. We know what the Sun is made of, not because we’ve been there, but because we expect the absorption spectrum of hydrogen and helium to be the same there as on Earth.[11] At the same time, we suppose that if God is fully rational, God understands things in the same way that we do (but clearly not at the same level), and that a rational universe[12] naturally follows from God’s rationality. This brings up more questions: Is the universe truly rational? If not, does that imply irrationality on the part of God? The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle The Heisenberg uncertainty principle is an incredible result of the formulation of quantum mechanics in the early part of last century. It essentially states that for any two “incompatible” (this has a precise definition we can skip past) observable quantities (e.g., position and momentum or the components of angular momentum), the more you know about one, the less you know about the other. For example, suppose you find a collection of electrons in the period at the end of this sentence. Knowing that each electron is in a small space (granted, a period is a very large space for an electron, but bear with me for a moment), each electron can be restated as having very little uncertainty, on average, of its location. The uncertainty principle then requires a much larger spread of uncertainty regarding the electrons’ momenta (i.e., large uncertainty). This idea is often confused with the observer effect,[13] but the Heisenberg uncertainty principle makes no statements about the measurement process itself. (In fact, failure to measure a particle in a certain place speaks volumes about its location.) Instead, the “clumsiness” is built right into the equations: the standard deviations (read: uncertainty) σ of the collection of measurements of type A and B on a large number of identical quantum states have minimum values: σ_A^2 σ_B^2≥(1/2i ⟨[A ̂,B ̂ ]⟩)^2 where the inner brackets form what is known as a commutator and the middle brackets represent an expectation value (sort of an expected average measurement). The question then becomes: do our equations preclude the possibility of God knowing both the position and momentum of an electron at the same time? That is, given that the uncertainty principle is an inherent fact, inseparable from particle behavior, can even an omniscient being know what we say is unknowable? In the case of the uncertainty principle, the answer comes quite readily with a little understanding[14] (but the idea will soon be complicated further). Consider Figure 1, which contains two examples of particle wave functions (i.e., solutions to the Schrödinger equation which represent probability amplitudes of position); the horizontal direction represents one spatial dimension. The top panel shows a smooth, periodic wave with a well-defined wavelength λ. From de Broglie’s formula, we know that the momentum p of such a particle would then be easily correlated with Planck’s constant h by: p=h/λ But if we were to ask, “Where is the particle?,” an easy answer escapes us. Conversely, the bottom panel shows an example of a particle in which “Where is the particle?” has an easy, well-defined answer (i.e., near the hump), but the idea of a single, certain wavelength (read: momentum) does not make much sense. From this simple example, it becomes clear that God may not ignore the uncertainty principle, but this has nothing to do with ignorance. It is just that the particle does not have simultaneous, well-defined positions and momenta. “Is the answer to this question, ‘No’?” presents the same predicament. When we deem only certain answers possible (“Yes,” “No,” “The particle is here,” etc.), then we find God cannot answer all of our questions. This seems to suggest a belief in the rationality of God, because we tend to think God could not possibly give an acceptable answer to an irrational question.[15] For example, if I asked, “God, what color is the dragon sitting on top of the reader’s head?,” I have indicated that I expect the answer to be a color. God could not give such an answer, but would (I think) reply with something along the lines of “There is no dragon,” for God cannot know the color of a nonexistent dragon. This requires us to refine our definition of omniscience to “knowing everything that can be known” (or “knowing everything it makes sense to know”) instead of the nonsensical “knowing everything.” Now, one could state that God, ultimately the creator of every electron in the universe, could know the simultaneous position and momentum of an electron if desired. But that would entail a different set of physical laws in which the uncertainty principle did not exist, and hence, we would be living in an entirely different universe. Thus, it seems that God has chosen to limit God’s knowledge in this universe. In theological circles, this is known as inherent omniscience—where God knows only what God chooses to know and which can be known—as opposed to total omniscience, where God knows everything that can be known. Perhaps it could be said that the physical universe is nothing more than what God chooses to know about it. A Rational Universe and Its Creator Other aspects of quantum mechanics are more difficult to resolve in terms of a rational God, but most physicists[16] and Christians[17] hang on, for good reason, to the idea of the complete rationality of the universe—it should “make sense.” Some of these perplexing problems are resolved with better physics. For example, wave/particle duality,[18] in which a quantum object shows evidence that it can be either a particle14 or a wave[19] depending on the situation it finds itself in, is contrary to any classical (i.e., Newtonian) object we know of. (Duality is related to the enigma of the “collapse of the wave function,”[20] in which a measurement forces an object to spontaneously choose a certain state as directed by applicable probabilities; that is, the wave manifests itself as a particle). However, wave/particle duality can be resolved with quantum field theory,[21] a more general and fundamental view of things. (There are many popular unorthodox views on how to resolve this as well.[22]) Other inherent contradictions and irrationalities in quantum mechanics are viewed as subjects which will be resolved with time. For instance, contrary to the recommendation of PETA, Erwin Schrödinger proposed a thought experiment in which a quantum state is projected onto a classical object such as a cat.[23] Schrödinger’s cat eventually enters a state of being alive and dead at the same time until someone checks on it. The clear irrationality of this situation rests only on our current lack of understanding of the mesoscopic bridge between large and small,[24] but no physicist would think that irrational or magical physics takes place between the two. So, while it is difficult to make a statement as bold as, “The universe has to make sense,” the vast majority of it does, and the parts that don’t seem at least predictably irrational,[25] most notably the probabilistic features of quantum mechanics. A better statement might be, “The universe makes sense but we don’t yet know how.” An irrational universe wouldn’t be worth studying because it wouldn’t be possible to understand anything about it, and while the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics takes an agnostic view of whether the universe should make sense,[26] most of the unorthodox interpretations (e.g., objective collapse,[27] many worlds,[28] and ensemble theories[29]) involve an element of realism. But what if it doesn’t? But let us suppose that the “correct” interpretation of quantum mechanics is an irrational one. What does that say about God? First, what appears to be irrational in quantum mechanics usually just means “not classical” or contrary to anything we can personally experience.[30] But on a divine level, irrationality would imply a lack of order, purpose, or sensibility, so the ideas are not easily comparable; in any case, we would find it difficult to think of a completely rational God creating a completely nonsensical system. Nevertheless, that begs the question: Is God necessarily rational in every aspect? Or put another way, if we had enough time, could we as rational creatures fully understand everything about God’s creation? The evidence points to a God that is at least partly rational. At the same time, we are unquestionably second-class citizens in the realms of knowledge and thinking, so the easy way out of this dilemma might be to just believe, for example, that God somehow “understands” paradoxes and the like. But, as developed above, such a position betrays our God-given good sense, so it seems that if we ever arrive at a point at which we can definitively state that a certain aspect of nature is irrational, we must at least, without necessarily going so far as to use the word irrational, allow the possibility of God having the ability to think in a way completely contrary to our ways of thinking.[31] This would not necessarily be a theological disaster; in Isaiah 55:8, God makes it clear that we don’t think like him. Nevertheless, irrationality implies a lack of control and understanding that we would find difficult to reconcile with the traditional Christian concept of God. Still, discovering a truly irrational property of the universe seems unlikely; string theory’s very existence hinges on its ability to make some sense of it all, and the last 13.8 billion years has yielded orders of magnitude more sense than nonsense. A heroic physicist has always emerged to explain the nonsense in the past,[32] and there’s no reason to think it won’t happen again. This should be comforting to Christians, because a Christian theology which incorporates an irrational God has, in the words of Ricky Ricardo, some serious splainin’ to do. Conclusion We physicists often become so cognitively enmeshed in abstractions that it can become difficult to separate useful constructs from reality.[33] All this talk of dualities and wave function collapses and cats ignores the fact that, quantum mechanically speaking, even with advances in decoherence theory,[34] we don’t even know what a measurement is. The more we know, the more we realize we don’t know. Science is a tiny glimpse of the nature of God, and thank goodness God reveals himself to us in other ways! On top of that, using creation to learn about God is much like going to the doctor; you’ll probably find out more about what you don’t have than what you do. Einstein had a problem with God “playing dice,” but we should keep in mind that God, unlike us, does not sit under an umbrella of true principles that must be chosen from. Rather, “the Lord gives wisdom, and from his mouth come knowledge and understanding” (Proverbs 2:6 NIV). Even Anselm’s definition of God as “that of which nothing greater can be thought” relies on our own ability to think, but we know our thoughts are limited. If God knows all there is, does God know all there isn’t? Can God create a rock so big he can’t lift it? We may never have satisfactory answers to questions like these. But we have to admit that even the cross seems irrational to us at some level—if it all made sense to us, God’s grace wouldn’t be so amazing—and sometimes the beauty of what we believe is that God knows what God is doing, even when we don’t. |

Steve Robinson is an associate professor of physics at Belmont University in Nashville, TN, where he teaches quantum mechanics and physical chemistry.

Steve received his PhD from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2007 with an emphasis on condensed matter physics and quantum computing. He is a deacon and teaches fifth-grade boys at his church and is married with three children. God loves Steve a lot for unknown reasons. |

REFERENCES

[1] H. E. Kyburg, Probability and the Logic of Rational Belief (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961).

[2] Assuming the veracity of this statement, I don’t mean that when I imagine something falling, it must fall at 9.8 m/s2. Rather, for example, that any thought (an “effect”) must be predicated by a physical cause; that is, it cannot be derived from sentience alone.

[3] A. Plantinga and M. Tooley, Knowledge of God, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2008).

[4] Jacobellis v. Ohio 378 U.S. 184 (1964).

[5] J. Foster, The Immaterial Self: A Defence of the Cartesian Dualist Conception of the Mind (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991).

[6] N. Malcolm, The Philosophical Review 69 (1960): 41–62.

[7] R. W. K. Paterson, Religious Studies 15 (1979): 1–23.

[8] T. Aquinas, Summa Theologica (ca. 1270); C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1952).

[9] C. Taliaferro, Journal of the American Academy of Religion LXI (1993): 553–566.

[10] A. Lansdown, Creation 17 (1995): 45.

[11] K. Lodders, The Astrophysical Journal 591 (2003): 1220–1247.

[12] M. T. Murphy, V. V. Flambaum, S. Muller, C. Henkel, Science 320 (2008): 1611–1613.

[13] C. Bruce, Schrödinger’s Rabbits: The Many Worlds of Quantum (Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2004).

[14] D. J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005).

[15] C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1940).

[16] R. B. Mann, Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 61 (2009): 139–150.

[17] D. J. Bartholomew, Uncertain Belief: Is It Rational to Be a Christian? (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996).

[18] M. Arndt, O. Nairz, J. Vos-Andreae, C. Keller, G. van der Zouw, and A. Zeilinger, Nature 401 (1999): 680–682.

[19] T. Young, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 92 (1802): 12–48.

[20] R. Shankar, Principles of Quantum Mechanics (New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1994).

[21] M. Cini, Annals of Physics 305 (2003): 83–95; A. Hobson, The Physics Teacher 45 (2007): 96–99.

[22] C. Mead, Collective Electrodynamics: Quantum Foundations of Electromagnetism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002); B. S. Dewitt and N. Graham, The Many World Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973); M. Richter et al., Physical Review Letters 102 (2009): 163002.

[23] J. D. Trimmer, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 124 (1980): 323–338.

[24] K. J. Thomas, J. T. Nicholls, M. Y. Simmons, M. Pepper, D. R. Mace, and D. A. Ritchie, Physical Review Letters 77 (1996): 135–138.

[25] B. Rosenblum and F. Kuttner, Quantum Enigma (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[26] J. S. Bell, Physics 1 (1964): 195–200.

[27] G. C. Ghirardi, A. Rimini, and T. Weber, Physical Review D 34 (1986): 470–491.

[28] M. Hemmo and I. Pitowsky, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 38 (2007): 333–350.

[29] L. E. Ballentine, Reviews of Modern Physics 42 (1970): 358–381.

[30] That is, it is difficult to define an area of physics as “irrational.” At some level, we just have to say “physics just is.”

[31] In other words, we would not just say, “God is infinitely smarter than we are.” Rather, that God has an understanding completely unfathomable and foreign to us.

[32] I. Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687); J. C. Maxwell, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 155 (1865): 459–512; A. Einstein, Annalen der Physik 354 (1916): 769–822; J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, and J. R. Schrieffer, Physical Review 108 (1957): 1175–1204.

[33] N. D. Mermin, Physics Today 62 (2009): 8–9.

[34] E. Joos, et al. Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory, 2nd ed. (Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2003).

[1] H. E. Kyburg, Probability and the Logic of Rational Belief (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961).

[2] Assuming the veracity of this statement, I don’t mean that when I imagine something falling, it must fall at 9.8 m/s2. Rather, for example, that any thought (an “effect”) must be predicated by a physical cause; that is, it cannot be derived from sentience alone.

[3] A. Plantinga and M. Tooley, Knowledge of God, (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2008).

[4] Jacobellis v. Ohio 378 U.S. 184 (1964).

[5] J. Foster, The Immaterial Self: A Defence of the Cartesian Dualist Conception of the Mind (New York, NY: Routledge, 1991).

[6] N. Malcolm, The Philosophical Review 69 (1960): 41–62.

[7] R. W. K. Paterson, Religious Studies 15 (1979): 1–23.

[8] T. Aquinas, Summa Theologica (ca. 1270); C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1952).

[9] C. Taliaferro, Journal of the American Academy of Religion LXI (1993): 553–566.

[10] A. Lansdown, Creation 17 (1995): 45.

[11] K. Lodders, The Astrophysical Journal 591 (2003): 1220–1247.

[12] M. T. Murphy, V. V. Flambaum, S. Muller, C. Henkel, Science 320 (2008): 1611–1613.

[13] C. Bruce, Schrödinger’s Rabbits: The Many Worlds of Quantum (Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2004).

[14] D. J. Griffiths, Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005).

[15] C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1940).

[16] R. B. Mann, Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith 61 (2009): 139–150.

[17] D. J. Bartholomew, Uncertain Belief: Is It Rational to Be a Christian? (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1996).

[18] M. Arndt, O. Nairz, J. Vos-Andreae, C. Keller, G. van der Zouw, and A. Zeilinger, Nature 401 (1999): 680–682.

[19] T. Young, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 92 (1802): 12–48.

[20] R. Shankar, Principles of Quantum Mechanics (New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1994).

[21] M. Cini, Annals of Physics 305 (2003): 83–95; A. Hobson, The Physics Teacher 45 (2007): 96–99.

[22] C. Mead, Collective Electrodynamics: Quantum Foundations of Electromagnetism (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002); B. S. Dewitt and N. Graham, The Many World Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973); M. Richter et al., Physical Review Letters 102 (2009): 163002.

[23] J. D. Trimmer, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 124 (1980): 323–338.

[24] K. J. Thomas, J. T. Nicholls, M. Y. Simmons, M. Pepper, D. R. Mace, and D. A. Ritchie, Physical Review Letters 77 (1996): 135–138.

[25] B. Rosenblum and F. Kuttner, Quantum Enigma (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[26] J. S. Bell, Physics 1 (1964): 195–200.

[27] G. C. Ghirardi, A. Rimini, and T. Weber, Physical Review D 34 (1986): 470–491.

[28] M. Hemmo and I. Pitowsky, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 38 (2007): 333–350.

[29] L. E. Ballentine, Reviews of Modern Physics 42 (1970): 358–381.

[30] That is, it is difficult to define an area of physics as “irrational.” At some level, we just have to say “physics just is.”

[31] In other words, we would not just say, “God is infinitely smarter than we are.” Rather, that God has an understanding completely unfathomable and foreign to us.

[32] I. Newton, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687); J. C. Maxwell, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 155 (1865): 459–512; A. Einstein, Annalen der Physik 354 (1916): 769–822; J. Bardeen, L. N. Cooper, and J. R. Schrieffer, Physical Review 108 (1957): 1175–1204.

[33] N. D. Mermin, Physics Today 62 (2009): 8–9.

[34] E. Joos, et al. Decoherence and the Appearance of a Classical World in Quantum Theory, 2nd ed. (Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2003).