"Great Gravity" is featured every edition of God & Nature Magazine, and tells the story of BNL physicist Bill Morse's journey through the world of muons and quarks, colliders and bubble chambers, with the heart of a committed Catholic and longtime-teacher of Sunday school. Read the first post in this series here.

A Bit of Perspective

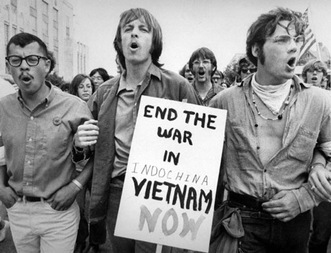

Vietnam War protestors

with Bill Morse

My father was manager of a wholesale appliance parts store in Portland, Maine, but he wanted to get into computers. He got a job as an apprentice computer tech with Western Union in N. Syracuse, New York, and we moved from Scarborough to New York in 1966. I loved Maine, but I also liked New York. The main reason was that summer jobs were plentiful and better paying than in Maine, and I needed the money to go to college. I got a job selling ice cream from an ice cream truck. I got two cents for every ten-cent ice cream bar I sold, and was making considerably more than minimum wage, which back then was one dollar an hour. I loved working outside, and I loved the kids. One little black boy stopped me every day, and asked for an ice cream bar. When I said, ”Ten cents,” he opened his fist to show a rock. I patiently told him every day that he needed to ask his mother for a dime. The last day before I went back to college, he stopped me, and asked for an ice cream. I said, "That will be one rock." Then I took the rock from his hand, and gave him the ice cream bar. He still had the most amazed look on his face as I looked in the rearview mirror before I turned the corner. My route consisted of a middle-class white neighborhood, a poor black neighborhood, and the Onondaga Indian reservation. In the white neighborhood, typically a kid would stop me and tell me to wait—they had to ask their mother if they had been good. Most of the time, they came out with a dime, but not always. The black neighborhood was better, but the Indian reservation was where I sold the most ice cream. Many of the men were drunk by early afternoon, and sometimes there were broken windows in the house, but five kids would run out, each with a dime. However, I once made a big mistake. There was a lacrosse match, which I had never seen before. I stopped, and the kids came running over. I was selling a lot of ice cream, but a guy came over, and said that he sold food at the lacrosse matches. I explained (very logically, I thought) that my truck was on a New York state road, to which he said, "This is Indian land," and wrestled me to the ground. He was obviously drunk, so I decided, since a crowd was gathering, that I could flip him off and run but we slid into a ditch. He was pushing my head down into the water and strangling me. I thought this was the end. I decided that I should stop struggling, take a deep breath, and then give one push with all I had. It worked. Somehow I pushed him off, got out of the ditch, and drove off. I told my boss, and he said he would call the chief. The next morning, my boss told me everything would be fine, but not to sell at the lacrosse matches anymore. I didn't have any trouble after that. I think one thing I learned from that summer is that all the kids were wonderful human beings, and it didn't matter whether they were white, black or red. One difference between the World War II generation and my generation, the Baby Boomer generation, is that the World War II generation was very much against mixed race marriages, while we thought they were fine. Once, when I was driving my daughter and some of her friends somewhere, they started talking about their grandmothers. One little girl with a white and a black parent said she loved her black grandmother, but her white grandmother made her sad, because she had never talked to her. This really tugged at my heart. If I had ever doubted that every human being is created in the image of God, I didn’t after that. Another different perspective between the World War II generation and the Baby Boomer generation was the Vietnam War, which was starting to heat up when I got to college at Stony Brook. The World War II generation argued that if they’d stopped Hitler in the 1930s, they wouldn’t have suffered the attack on Pearl Harbor in the 1940s—therefore, we had to stop the Ho Chi Ming now. I argued that the Ho Chi Ming would never attack Hawaii! The Vietnam War was so terrible in so many ways. In 1968, we took over the Stony Brook library to protest the war. It was great; we were putting up barricades, and everything. However, around 2am, I remembered that I had an E&M (electricity and magnetism) test that afternoon, and I had to study! I went downstairs, and over the barricades. There was a single Suffolk County policeman there at the door. I asked him if I could leave. He said, "Sure, but you can't come back." I told him I had to study for my E&M test. He said he thought that was a very good idea. At 4am, the Suffolk County police went in over the barricades. There were a lot of bloody heads and a lot of arrests. The pictures in the papers reminded me of Johnny on Munjoy Hill. At our 40th Scarborough High School Reunion last year, one of the girls we graduated with, Jo-Deen, said that we had never thanked our Vietnam veterans when they came back from Vietnam, and she gave each one of them a pin and a hug. About one dozen of our class served in Vietnam. I have never seen so many tears from fifty-year-old men. Read the next post in this series here.

|