God and Nature Summer 2023

By Ken Touryan and Cheryl Touryan

Feathers are so common in our world that we seldom give them much thought, even though they are one of the wonders of the natural world. They are unique to birds, and their complex structures are marvels of ingenuity that defy the most advanced human technologies. Naturalist Thor Hanson explores their amazing features in his book Feathers (1).

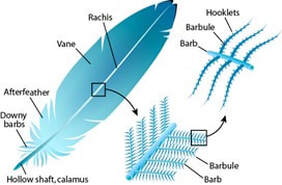

Feathers are made of fibrous proteins called keratin. As they start to grow, they are connected to blood vessels through skin follicles, much like our skin follicles that produce hair. Once the feather is mature, it is disconnected from the blood source, which helps decrease its weight.

Feathers do degenerate with age, so birds go through molting seasons when the old feathers are shed and new ones form. During this time, the blood is again connected to the follicle. There are also tiny muscles surrounding the follicles that enable the bird to move its feathers for flight, or for displays such as those of the male turkey or peacock.

The four primary functions of feathers identified by Thor Hanson are: insulation, water proofing, aerodynamics, and color.

Feathers are so common in our world that we seldom give them much thought, even though they are one of the wonders of the natural world. They are unique to birds, and their complex structures are marvels of ingenuity that defy the most advanced human technologies. Naturalist Thor Hanson explores their amazing features in his book Feathers (1).

Feathers are made of fibrous proteins called keratin. As they start to grow, they are connected to blood vessels through skin follicles, much like our skin follicles that produce hair. Once the feather is mature, it is disconnected from the blood source, which helps decrease its weight.

Feathers do degenerate with age, so birds go through molting seasons when the old feathers are shed and new ones form. During this time, the blood is again connected to the follicle. There are also tiny muscles surrounding the follicles that enable the bird to move its feathers for flight, or for displays such as those of the male turkey or peacock.

The four primary functions of feathers identified by Thor Hanson are: insulation, water proofing, aerodynamics, and color.

The incredible variety of colors present in feathers is itself a miracle to behold. |

INSULATION

Insulation is measured as a heat-to-weight ratio, and down feathers are legendary in their heat-retaining ability. Modern technology has not been able to match their amazing capacity. Air is a poor conductor of heat, and the secret of down feathers is their ability to trap air very efficiently while weighing very little. This feature also gives added buoyancy to waterfowl as well as providing a warm, safe environment for eggs and hatchlings. Down has been used for millennia in bedding and clothing.

WATERPROOFING

The waterproofing ability of feathers for waterfowl is just as marvelous. Feathers become waterproof as a result of being “preened” or treated with oil (which the bird gets from its oil gland, just above the tail), as well as due to their unique structure. The tight interlocking barbules in the outer feathers make them impenetrable to water.

FLIGHT

As for the aerodynamic design of feathers, it has been shown that each individual wing feather has the shape of an airfoil (a feature human engineers learned to incorporate into their designs of aircraft). Wing feathers are lightweight, but, when joined together, they become a firm airfoil that provides lift and minimizes drag for the bird. The connection is done by the barbules and hooklets on each individual barb coming off the shaft of the feather. However, feathers remain flexible, which reduces drag (resistance) when the bird lifts its wings on the upstroke. Many birds also separate the wing feathers during the upward stroke to further reduce drag. In addition, the tips of flight feathers (wing and tail) are designed to reduce turbulence, making smooth flight possible.

COLOR

The incredible variety of colors present in feathers is itself a miracle to behold. The ultimate example of extravagance in color and beauty is the male peacock’s tail. Such bright colors are used for attracting mates (mostly in males), while duller colors serve as camouflage. Feather colors are produced in various ways: some involve melanin in the keratin of the actual feather; some are a result of light refraction due to structure of the keratin (peacock colors); and some are influenced by the bird’s diet. For example, the flamingo’s pink color comes from the carotenoids in the algae and crustaceans it consumes.

Birds also depend on their feathers for personal protection (armor in addition to camouflage), environmental awareness (sensory feathers), and protection from the weather (sunscreen protection). And, of course, they ‘feather their nests’ to protect their young.

Insulation is measured as a heat-to-weight ratio, and down feathers are legendary in their heat-retaining ability. Modern technology has not been able to match their amazing capacity. Air is a poor conductor of heat, and the secret of down feathers is their ability to trap air very efficiently while weighing very little. This feature also gives added buoyancy to waterfowl as well as providing a warm, safe environment for eggs and hatchlings. Down has been used for millennia in bedding and clothing.

WATERPROOFING

The waterproofing ability of feathers for waterfowl is just as marvelous. Feathers become waterproof as a result of being “preened” or treated with oil (which the bird gets from its oil gland, just above the tail), as well as due to their unique structure. The tight interlocking barbules in the outer feathers make them impenetrable to water.

FLIGHT

As for the aerodynamic design of feathers, it has been shown that each individual wing feather has the shape of an airfoil (a feature human engineers learned to incorporate into their designs of aircraft). Wing feathers are lightweight, but, when joined together, they become a firm airfoil that provides lift and minimizes drag for the bird. The connection is done by the barbules and hooklets on each individual barb coming off the shaft of the feather. However, feathers remain flexible, which reduces drag (resistance) when the bird lifts its wings on the upstroke. Many birds also separate the wing feathers during the upward stroke to further reduce drag. In addition, the tips of flight feathers (wing and tail) are designed to reduce turbulence, making smooth flight possible.

COLOR

The incredible variety of colors present in feathers is itself a miracle to behold. The ultimate example of extravagance in color and beauty is the male peacock’s tail. Such bright colors are used for attracting mates (mostly in males), while duller colors serve as camouflage. Feather colors are produced in various ways: some involve melanin in the keratin of the actual feather; some are a result of light refraction due to structure of the keratin (peacock colors); and some are influenced by the bird’s diet. For example, the flamingo’s pink color comes from the carotenoids in the algae and crustaceans it consumes.

Birds also depend on their feathers for personal protection (armor in addition to camouflage), environmental awareness (sensory feathers), and protection from the weather (sunscreen protection). And, of course, they ‘feather their nests’ to protect their young.

THE DESIGNER

Scientists who study feathers often use the words ‘miraculous’ and ‘expertly designed’ when referring to them, without acknowledging a Designer or a Creator God. The engineering genius of God, as well as his flamboyant artistry, are displayed in the natural world everywhere, but feathers are a particularly striking example.

Such miracles call forth something akin to what King David wrote in Psalm 9:1: “I will praise you, O Lord, with all my heart. I will tell of your wonders.” “I will praise you, O Lord, with all my heart. I will tell of your wonders.” Next time you pick up a fallen feather, consider that you are looking at one of the wonders of the world—and thank the Designer.

References:

1. Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle, by Thor Hanson, published by Basic Books, 2011.

For more information on this topic see: The Thing with Feathers: The Surprising Lives of Birds and What They Reveal About Being Human, by Noah Stryker, Riverhead Books, March, 2014; and Feathers Not Just for Flying, by Melissa Stewart and Sarah Brannen, Charlesbridge, February 2014.

Kenell (Ken) Touryan retired from the National Renewable Energy laboratory in 2007 as chief technology analyst. He spent the next eight years as visiting professor at the American University of Armenia (an affiliate of UC Berkeley). He received his PhD in Mechanical and Aeronautical Sciences from Princeton University with a minor in Physics. His first 16 years were spent at Sandia National Laboratories as Manager of R&D projects in various defense and advanced energy systems. He has published some 95 papers in refereed journals, authored three books, and co-owns several patents.

Cheryl Touryan is a scientist by osmosis, having participated with Dr. Ken Touryan in ASA activities for over 50 years. Along with being a wife and mother, Cheryl has been involved with ministry to marginalized women and children in developing countries for forty years, part of that time with World Vision. Cheryl and Ken are passionate about encouraging young people to approach the natural world with wonder, which hopefully will lead to worship of the Creator God. They wrote a book together for young people called Wonders in our World. Currently living in a retirement village, Cheryl continues to follow her passion by writing monthly articles on such topics for the local community.

Scientists who study feathers often use the words ‘miraculous’ and ‘expertly designed’ when referring to them, without acknowledging a Designer or a Creator God. The engineering genius of God, as well as his flamboyant artistry, are displayed in the natural world everywhere, but feathers are a particularly striking example.

Such miracles call forth something akin to what King David wrote in Psalm 9:1: “I will praise you, O Lord, with all my heart. I will tell of your wonders.” “I will praise you, O Lord, with all my heart. I will tell of your wonders.” Next time you pick up a fallen feather, consider that you are looking at one of the wonders of the world—and thank the Designer.

References:

1. Feathers: The Evolution of a Natural Miracle, by Thor Hanson, published by Basic Books, 2011.

For more information on this topic see: The Thing with Feathers: The Surprising Lives of Birds and What They Reveal About Being Human, by Noah Stryker, Riverhead Books, March, 2014; and Feathers Not Just for Flying, by Melissa Stewart and Sarah Brannen, Charlesbridge, February 2014.

Kenell (Ken) Touryan retired from the National Renewable Energy laboratory in 2007 as chief technology analyst. He spent the next eight years as visiting professor at the American University of Armenia (an affiliate of UC Berkeley). He received his PhD in Mechanical and Aeronautical Sciences from Princeton University with a minor in Physics. His first 16 years were spent at Sandia National Laboratories as Manager of R&D projects in various defense and advanced energy systems. He has published some 95 papers in refereed journals, authored three books, and co-owns several patents.

Cheryl Touryan is a scientist by osmosis, having participated with Dr. Ken Touryan in ASA activities for over 50 years. Along with being a wife and mother, Cheryl has been involved with ministry to marginalized women and children in developing countries for forty years, part of that time with World Vision. Cheryl and Ken are passionate about encouraging young people to approach the natural world with wonder, which hopefully will lead to worship of the Creator God. They wrote a book together for young people called Wonders in our World. Currently living in a retirement village, Cheryl continues to follow her passion by writing monthly articles on such topics for the local community.