God and Nature Winter 2020

By Matthew Pevarnik

We are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about astronomy.--Simon Newcomb in 1888.

Simon Newcomb famously proclaimed in 1888 that we were nearing the limits of our knowledge about astronomy, although he gradually updated his perspective over the years. Later, he called astronomy an “illimitable field, the existence of which was scarcely suspected ten years ago” (1).

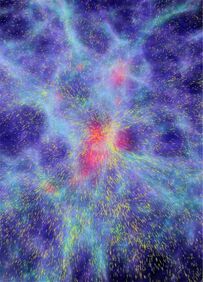

The furthest object in Newcomb’s universe was no further than our own galaxy. It was not until the 1920s that we determined there was anything beyond the Milky Way, with Edwin Hubble’s discovery of a Cepheid star in the Andromeda Galaxy. This star was originally estimated to be over a million light years (or ~5.9x10^18 miles) away. We now estimate some two trillion galaxies out to a distance of z=8 (approximately 13.1 billion light years away from Earth) (2). Contained in these two trillion galaxies are at least 5x10^21 stars. By comparison, there are approximately as many grains of sand on the entire earth as there are estimated stars in the observable universe. It is mind boggling to go to the beach and imagine that for each grain of sand there is a star out in the universe.

We are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about astronomy.--Simon Newcomb in 1888.

Simon Newcomb famously proclaimed in 1888 that we were nearing the limits of our knowledge about astronomy, although he gradually updated his perspective over the years. Later, he called astronomy an “illimitable field, the existence of which was scarcely suspected ten years ago” (1).

The furthest object in Newcomb’s universe was no further than our own galaxy. It was not until the 1920s that we determined there was anything beyond the Milky Way, with Edwin Hubble’s discovery of a Cepheid star in the Andromeda Galaxy. This star was originally estimated to be over a million light years (or ~5.9x10^18 miles) away. We now estimate some two trillion galaxies out to a distance of z=8 (approximately 13.1 billion light years away from Earth) (2). Contained in these two trillion galaxies are at least 5x10^21 stars. By comparison, there are approximately as many grains of sand on the entire earth as there are estimated stars in the observable universe. It is mind boggling to go to the beach and imagine that for each grain of sand there is a star out in the universe.

"By faith all Christians would believe that God is the ultimate creator and source of the sun’s light, regardless of whether or not we understand the physical mechanism behind the production of starlight." |

The average size of a star is about that of our sun, which is already 110 times larger than the Earth. Many of the 5x10^21 stars will also have exoplanets orbiting around them, with some 50 billion exoplanets estimated to be in the Milky Way Galaxy alone (3). And we now understand where most of these astrophysical objects come from, including the origin of the elements themselves (4).

Faced with some sort of beginning to our universe, spacetime theorems like the famous Borde-Guth-Vilenkin paper discuss what could lie beyond this boundary. One possibility is “… that the boundary of the inflating region corresponds to the beginning of the Universe in a quantum nucleation event” (5). Other papers explore bouncing cosmologies, where our universe is just one of a repeating cycle of universes of (infinite?) repetition (6).

Where then does the limit of our knowledge lie? It seems unlikely that we could measure any kind of structure like a multiverse beyond our present universe. Some have proposed detecting bubble collisions imprinted on the cosmic microwave background anisotropies or measuring the so-called ‘dark’ flow from the landscape multiverse (7,8).

At what point does it make sense to insert God into these scientific inquiries into his creation? One approach would be to take the route of British apologist John Edwards, who in 1696 used the lack of an explanation for how our sun produces light as evidence for God’s direct handiwork (9). It would be over 200 years before any scientific explanation for this question was in sight—there was no way to even begin to imagine the solution without advanced knowledge of nuclear physics. We find this kind of argument for God’s existence and handiwork the strongest when we understand the least.

Yet at the same time, the comments by Edwards are based upon a healthy part of the Christian worldview. As Christians, it is by faith that we trust that all things were created by and for Christ, and that he holds all things together (Col 1:15-17, Heb 1:2-3). Thus, it is a natural thing for both for Edwards and modern believers to give credit to God for all of science, including the things not yet known. By faith all Christians would believe that God is the ultimate creator and source of the sun’s light, regardless of whether or not we understand the physical mechanism behind the production of starlight. This belief (which is something Christians know to be true) can be challenging to communicate properly to those outside of the household of faith, and careful wording is encouraged. Far too often this proper belief of Christians appears to be a call to abandon scientific inquiry.

For example, a common form of the Kalam Cosmological Argument can be seen as a god-of-the-gaps argument. That is, it is obvious that our universe didn’t arise from truly nothing and its origin must reside in something outside the spacetime of our universe. Yet for a physicist that doesn’t mean that it began via a supernatural being speaking it into existence. Physicists undauntingly build models of the formation of our universe and painstakingly aim to make testable predictions of the best of the models.

Thus, taking the origin of the universe as direct evidence of God’s handiwork doesn’t translate well for most physicists or cosmologists. It sounds as if we are saying that we will never be able to figure out more about our universe, and we should stop asking questions at some point. That is, it sounds like saying we are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about cosmology--and that is the end of cosmology as a science.

Therefore, in today’s world, the matter of Christian knowledge (through reasonable belief) vs. scientific explanations needs more careful thought and nuanced phrasing. I believe that once we communicate this more clearly to the world and encourage the scientific community to never stop asking questions about the universe and the constants of nature, we will see God’s glory revealed in ways that we never could have possibly imagined.

References

1. Newcomb, S. The Universe as an Organism. Science 17, (1903).

2. Conselice, C. J., Wilkinson, A., Duncan, K. & Mortlock, A. The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and its Implications. The Astrophysical Journal 830, 83 (2016).

3. Guo, J., Zhang, F., Chen, X. & Han, Z. Probability Distribution of Terrestrial Planets in Habitable Zones Around Host Stars. Astrophysics and Space Science 323, 367–373 (2009).

4. Johnson, J. Origin of the Elements in the Solar System | Science Blog from the SDSS.

5. Borde, A., Guth, A. H. & Vilenkin, A. Inflationary Spacetimes Are Incomplete in Past Directions. Physical Review Letters 90, 4 (2003).

6. Levy, A. M., Ijjas, A. & Steinhardt, P. J. Scale-invariant perturbations in ekpyrotic cosmologies without fine-tuning of initial conditions. Physical Review D 92, 063524 (2015).

7. Wainwright, C. L. et al. Simulating the universe(s): from cosmic bubble collisions to cosmological observables with numerical relativity. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2014, (2013).

8. Mersini-Houghton, L. & Holman, R. ‘Tilting’ the universe with the landscape multiverse: the dark flow. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2009, (2009).

9. Edwards, J. A Demonstration of the Existence and Providence of God, from the Contemplation of the Visible Structure of the Greater and the Lesser World in Two Parts. (1696).

Dr. Matthew Pevarnik received his Ph.D. in Physics from the University of California, Irvine, with a focus on the biophysics of ion channels. He is presently an Assistant Professor of Physics at Regent University, where he teaches a number of courses on Origins and the intersection of physics and faith.

Faced with some sort of beginning to our universe, spacetime theorems like the famous Borde-Guth-Vilenkin paper discuss what could lie beyond this boundary. One possibility is “… that the boundary of the inflating region corresponds to the beginning of the Universe in a quantum nucleation event” (5). Other papers explore bouncing cosmologies, where our universe is just one of a repeating cycle of universes of (infinite?) repetition (6).

Where then does the limit of our knowledge lie? It seems unlikely that we could measure any kind of structure like a multiverse beyond our present universe. Some have proposed detecting bubble collisions imprinted on the cosmic microwave background anisotropies or measuring the so-called ‘dark’ flow from the landscape multiverse (7,8).

At what point does it make sense to insert God into these scientific inquiries into his creation? One approach would be to take the route of British apologist John Edwards, who in 1696 used the lack of an explanation for how our sun produces light as evidence for God’s direct handiwork (9). It would be over 200 years before any scientific explanation for this question was in sight—there was no way to even begin to imagine the solution without advanced knowledge of nuclear physics. We find this kind of argument for God’s existence and handiwork the strongest when we understand the least.

Yet at the same time, the comments by Edwards are based upon a healthy part of the Christian worldview. As Christians, it is by faith that we trust that all things were created by and for Christ, and that he holds all things together (Col 1:15-17, Heb 1:2-3). Thus, it is a natural thing for both for Edwards and modern believers to give credit to God for all of science, including the things not yet known. By faith all Christians would believe that God is the ultimate creator and source of the sun’s light, regardless of whether or not we understand the physical mechanism behind the production of starlight. This belief (which is something Christians know to be true) can be challenging to communicate properly to those outside of the household of faith, and careful wording is encouraged. Far too often this proper belief of Christians appears to be a call to abandon scientific inquiry.

For example, a common form of the Kalam Cosmological Argument can be seen as a god-of-the-gaps argument. That is, it is obvious that our universe didn’t arise from truly nothing and its origin must reside in something outside the spacetime of our universe. Yet for a physicist that doesn’t mean that it began via a supernatural being speaking it into existence. Physicists undauntingly build models of the formation of our universe and painstakingly aim to make testable predictions of the best of the models.

Thus, taking the origin of the universe as direct evidence of God’s handiwork doesn’t translate well for most physicists or cosmologists. It sounds as if we are saying that we will never be able to figure out more about our universe, and we should stop asking questions at some point. That is, it sounds like saying we are probably nearing the limit of all we can know about cosmology--and that is the end of cosmology as a science.

Therefore, in today’s world, the matter of Christian knowledge (through reasonable belief) vs. scientific explanations needs more careful thought and nuanced phrasing. I believe that once we communicate this more clearly to the world and encourage the scientific community to never stop asking questions about the universe and the constants of nature, we will see God’s glory revealed in ways that we never could have possibly imagined.

References

1. Newcomb, S. The Universe as an Organism. Science 17, (1903).

2. Conselice, C. J., Wilkinson, A., Duncan, K. & Mortlock, A. The Evolution of Galaxy Number Density at z < 8 and its Implications. The Astrophysical Journal 830, 83 (2016).

3. Guo, J., Zhang, F., Chen, X. & Han, Z. Probability Distribution of Terrestrial Planets in Habitable Zones Around Host Stars. Astrophysics and Space Science 323, 367–373 (2009).

4. Johnson, J. Origin of the Elements in the Solar System | Science Blog from the SDSS.

5. Borde, A., Guth, A. H. & Vilenkin, A. Inflationary Spacetimes Are Incomplete in Past Directions. Physical Review Letters 90, 4 (2003).

6. Levy, A. M., Ijjas, A. & Steinhardt, P. J. Scale-invariant perturbations in ekpyrotic cosmologies without fine-tuning of initial conditions. Physical Review D 92, 063524 (2015).

7. Wainwright, C. L. et al. Simulating the universe(s): from cosmic bubble collisions to cosmological observables with numerical relativity. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2014, (2013).

8. Mersini-Houghton, L. & Holman, R. ‘Tilting’ the universe with the landscape multiverse: the dark flow. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2009, (2009).

9. Edwards, J. A Demonstration of the Existence and Providence of God, from the Contemplation of the Visible Structure of the Greater and the Lesser World in Two Parts. (1696).

Dr. Matthew Pevarnik received his Ph.D. in Physics from the University of California, Irvine, with a focus on the biophysics of ion channels. He is presently an Assistant Professor of Physics at Regent University, where he teaches a number of courses on Origins and the intersection of physics and faith.