God and Nature Fall 2023

By Anikó Albert

Those involved in the science-and-faith dialogue often find themselves pushing back against two opposing falsehoods that sadly feed each other in a vicious cycle. On one side is the idea that “science has disproven God,” claimed by some vocal atheists; on the other, some religious people’s belief that accepting mainstream science, at least in some areas, would be contrary to their faith. Each side points to the other as evidence they are right: “The atheists’ science denies God!” “The religionists deny science!”

But is science denialism, as it’s often called, strongly linked to religiosity? Or is it, as some have suggested (1), more or as much a question of politicized identity? Why would so many people who identify as conservative Christians, especially in the United States, reject the scientific consensus in such disparate areas as the theory of evolution, anthropogenic climate change, and the effectiveness of vaccines?

These are complex questions I can’t hope to answer, but I can perhaps expand our thinking about what drives denialism by presenting a strange case most English speakers would not have heard of: the militant rejection of the linguistic classification of Hungarian as a Finno-Ugric (Uralic) language by many of its native speakers.

Those involved in the science-and-faith dialogue often find themselves pushing back against two opposing falsehoods that sadly feed each other in a vicious cycle. On one side is the idea that “science has disproven God,” claimed by some vocal atheists; on the other, some religious people’s belief that accepting mainstream science, at least in some areas, would be contrary to their faith. Each side points to the other as evidence they are right: “The atheists’ science denies God!” “The religionists deny science!”

But is science denialism, as it’s often called, strongly linked to religiosity? Or is it, as some have suggested (1), more or as much a question of politicized identity? Why would so many people who identify as conservative Christians, especially in the United States, reject the scientific consensus in such disparate areas as the theory of evolution, anthropogenic climate change, and the effectiveness of vaccines?

These are complex questions I can’t hope to answer, but I can perhaps expand our thinking about what drives denialism by presenting a strange case most English speakers would not have heard of: the militant rejection of the linguistic classification of Hungarian as a Finno-Ugric (Uralic) language by many of its native speakers.

...there are some interesting parallels between historical comparative linguistics and evolution. |

Why, what’s so special about Hungarian?

Nothing much, of course, when considering the diversity of 7000 or so extant languages (2) in the world. But, as western tourists like to testify, it is just “so weird and different!” right there in the middle of Europe. It doesn’t look or sound like any of the languages spoken anywhere around it, which are all from various familiar branches—Slavic, Germanic, and Romance—of the vast Indo-European family that covers most of Europe and parts of West and South Asia (3).

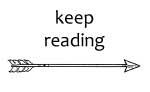

But while Hungarian might look lonely, it is not alone. As early as the 17th century, around the same time that scholars were discovering similarities between more and more languages of what would turn out to be that large Indo-European group, some also turned their eyes to the odd-ones-out of Europe and noted correspondences between Finnish, Sámi, and Hungarian. In the next two centuries, the comparative method was perfected, and, as travel into the Russian Empire became more feasible, many other related languages were described and added to the family, named Finno-Ugric in the 19th century after the Finnic and Ugric sub-groups that were then thought to geographically bookend the range. By the turn of the 20th century, it became clear that the Samoyedic languages should be included, and the language family was renamed Uralic after the Ural Mountains that rise above their presumed ancestral homeland (4).

For historical reasons, however, Finno-Ugric is the common term used in Hungary, both by those who defend the linguistic consensus and those who reject it.

So how do we know which languages belong to which language family? How does this comparative method work?

When we study a foreign language, we can’t help noticing what words or grammatical features are similar—or, on the contrary, are completely different—from those in our native language. When languages are closely related, like Spanish or Italian, words that sound similar are likely to in fact descend from the same ancestral word in Latin (albeit spoken “Vulgar” Latin, not what Cicero wrote). It’s not hard to figure out that Italian cantàre and Spanish cantar both descend from the same Latin verb that also means ‘to sing’. It’s less immediately obvious that Spanish hijo (‘son’) comes from Latin filius (more exactly, filium, the accusative form) just as directly as Italian figlio, but it does—it’s just that the consonants in the Spanish word changed a little more. We know that hijo is part of the large Romance family descending from filius (6) because the two changes that make it sound so different happened not only in this word but in many others as well (facere -> hacer, fabulare -> hablar, ferrus -> hierro, fumus -> humo, folia ->hoja.) They are, in other words, systematic, regular sound changes.

It is these regular sound correspondences between languages, not superficial similarities, that linguists look for when they try to determine which languages descend from the same ancestor, called a protolanguage, and thus belong to the same language family. In most cases, of course, we’re not so lucky as to have a well-attested protolanguage like Latin to rely on. Linguists instead compare—hence the terms comparative method and comparative linguistics—the core vocabulary (basic numbers, parts of the body, family relationships, etc.) of candidate languages, compile possible lists of cognates (related words), and try to establish regular sound correspondences between them. Once they have those correspondences, they come up with hypotheses on how the various attested (known) forms in the daughter languages could have come about, and work backwards through the sound changes that most likely occurred to reconstruct the word in the protolanguage (7).

These reconstructed forms, marked by asterisks to distinguish them from attested words, are of course only best guesses, more mathematical expressions of what can be established based on limited data than the exact word we can affirm some group of people spoke at a specific time. Full reconstruction of a protolanguage is impossible since a lot is lost without leaving a trace in any daughter language.

So what’s the story with Hungarian?

Despite its limitations, the method can usually determine which languages are related to each other even when they are very different today. Finns and Hungarians can’t understand a word of each other’s language, but the comparative method can establish beyond reasonable doubt that the two languages have a common ancestor. Hungarians learn this in school and can typically name a cognate or two: kala and hal (‘fish’), vesi and víz (‘water’) are easy to remember.

But these single examples people tend to recall can be unimpressive, and the point is often missed—it’s not just kala and hal but over a dozen other cognates in other Uralic languages (Sámi kuollē, Mordvin kal, Mari kol, Khanty kul or (different dialect) χul, Mansi kōl or χūl, Nenets χāľe, and more (8). And the word-initial k -> h change in Hungarian is regular, occurring whenever the k is followed by a back vowel.

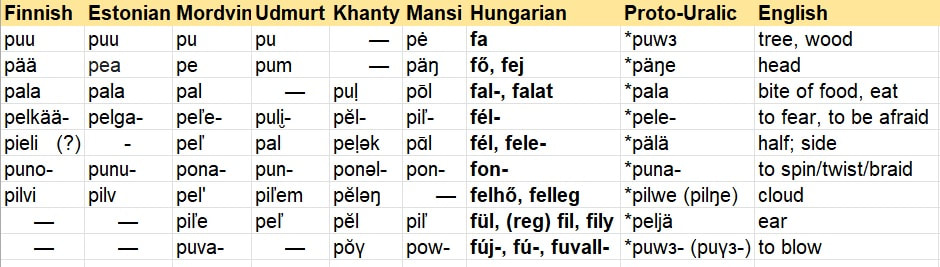

Here is a table with another set of cognates from selected Uralic languages, showing a regular word-initial p -> f correspondence for Hungarian (9). (There are many more cognates, and some of the languages have significant dialectal variation with additional forms.)

Nothing much, of course, when considering the diversity of 7000 or so extant languages (2) in the world. But, as western tourists like to testify, it is just “so weird and different!” right there in the middle of Europe. It doesn’t look or sound like any of the languages spoken anywhere around it, which are all from various familiar branches—Slavic, Germanic, and Romance—of the vast Indo-European family that covers most of Europe and parts of West and South Asia (3).

But while Hungarian might look lonely, it is not alone. As early as the 17th century, around the same time that scholars were discovering similarities between more and more languages of what would turn out to be that large Indo-European group, some also turned their eyes to the odd-ones-out of Europe and noted correspondences between Finnish, Sámi, and Hungarian. In the next two centuries, the comparative method was perfected, and, as travel into the Russian Empire became more feasible, many other related languages were described and added to the family, named Finno-Ugric in the 19th century after the Finnic and Ugric sub-groups that were then thought to geographically bookend the range. By the turn of the 20th century, it became clear that the Samoyedic languages should be included, and the language family was renamed Uralic after the Ural Mountains that rise above their presumed ancestral homeland (4).

For historical reasons, however, Finno-Ugric is the common term used in Hungary, both by those who defend the linguistic consensus and those who reject it.

So how do we know which languages belong to which language family? How does this comparative method work?

When we study a foreign language, we can’t help noticing what words or grammatical features are similar—or, on the contrary, are completely different—from those in our native language. When languages are closely related, like Spanish or Italian, words that sound similar are likely to in fact descend from the same ancestral word in Latin (albeit spoken “Vulgar” Latin, not what Cicero wrote). It’s not hard to figure out that Italian cantàre and Spanish cantar both descend from the same Latin verb that also means ‘to sing’. It’s less immediately obvious that Spanish hijo (‘son’) comes from Latin filius (more exactly, filium, the accusative form) just as directly as Italian figlio, but it does—it’s just that the consonants in the Spanish word changed a little more. We know that hijo is part of the large Romance family descending from filius (6) because the two changes that make it sound so different happened not only in this word but in many others as well (facere -> hacer, fabulare -> hablar, ferrus -> hierro, fumus -> humo, folia ->hoja.) They are, in other words, systematic, regular sound changes.

It is these regular sound correspondences between languages, not superficial similarities, that linguists look for when they try to determine which languages descend from the same ancestor, called a protolanguage, and thus belong to the same language family. In most cases, of course, we’re not so lucky as to have a well-attested protolanguage like Latin to rely on. Linguists instead compare—hence the terms comparative method and comparative linguistics—the core vocabulary (basic numbers, parts of the body, family relationships, etc.) of candidate languages, compile possible lists of cognates (related words), and try to establish regular sound correspondences between them. Once they have those correspondences, they come up with hypotheses on how the various attested (known) forms in the daughter languages could have come about, and work backwards through the sound changes that most likely occurred to reconstruct the word in the protolanguage (7).

These reconstructed forms, marked by asterisks to distinguish them from attested words, are of course only best guesses, more mathematical expressions of what can be established based on limited data than the exact word we can affirm some group of people spoke at a specific time. Full reconstruction of a protolanguage is impossible since a lot is lost without leaving a trace in any daughter language.

So what’s the story with Hungarian?

Despite its limitations, the method can usually determine which languages are related to each other even when they are very different today. Finns and Hungarians can’t understand a word of each other’s language, but the comparative method can establish beyond reasonable doubt that the two languages have a common ancestor. Hungarians learn this in school and can typically name a cognate or two: kala and hal (‘fish’), vesi and víz (‘water’) are easy to remember.

But these single examples people tend to recall can be unimpressive, and the point is often missed—it’s not just kala and hal but over a dozen other cognates in other Uralic languages (Sámi kuollē, Mordvin kal, Mari kol, Khanty kul or (different dialect) χul, Mansi kōl or χūl, Nenets χāľe, and more (8). And the word-initial k -> h change in Hungarian is regular, occurring whenever the k is followed by a back vowel.

Here is a table with another set of cognates from selected Uralic languages, showing a regular word-initial p -> f correspondence for Hungarian (9). (There are many more cognates, and some of the languages have significant dialectal variation with additional forms.)

byIf the evidence is this strong, what’s the problem? Why do some Hungarians reject it?

As is often noted, there are some interesting parallels between historical comparative linguistics and evolution. Both involve descent with modification from a common ancestor over long periods of time—much shorter in the case of languages, but still beyond what the human mind can intuitively grasp. In both cases, understanding how small changes can add up over time to lead to something very different and new requires some education, so it would make sense that people might struggle with both concepts.

But Finns, Estonians, and speakers of the many Uralic minority languages in Russia have no doubts about their languages being part of the Uralic family together with Hungarian. Denying this well-established fact is unique to Hungarians. Why? What is driving this strange form of denialism? There are several possible factors.

One of them is straightforward and stands out on the map: the other Uralic languages have relatives near them, while Hungarian is far away, and on its own. As a result of this distance, Hungarian has no close relatives—no language with which the relationship is obvious and some mutual intelligibility exists. The experience that Finns have with Estonians (or Italians with Spaniards, Slavic speakers with each other, etc.) is one Hungarians never get to share. It’s perhaps easier to imagine that one’s language is something completely different in this situation.

But the main stumbling block is historical. Back in the 19th century, when the Finno-Ugric theory first rose to general attention in in Hungary, the country was under Hapsburg rule. There had been several defeated uprisings, and before all that, occupation by the Ottoman Empire. Hungarians had not been independent for several centuries, and as people often do in such situations, they were holding on fast to stories of a mythologized, glorious past. But the Finno-Ugric relatives the linguists were proposing were nothing like the Hungarian heroes of old were supposed to be—they were not the skilled horsemen of legend whose arrows western Europe feared in the 10th century. They mostly lived in cold places way up north and were humble farmers, fishermen, or reindeer herders. And they had no countries of their own either. They were no help to flailing national pride.

So a conspiracy theory quickly took hold: one of those linguist guys is German, so “Finno-Ugrism” must be an evil Hapsburg plot to break the Hungarian spirit! Over time, the theory could be adjusted and projected onto anyone suspected of wanting to keep Hungarians down—the Russians were thought to be “pushing” Finno-Ugric linguistics during the Soviet occupation, even though they weren’t (they had little interest in fostering a pan-Uralic identity among minorities in the Soviet Union). Alternative “theories” have abounded over the years and ranged from the plausible but wrong (a relationship with Turkic languages instead) to the pseudo-historical or insane (Sumerians, aliens from Sirius, etc.) Many of them persist today even though modern linguists emphasize that the Finno-Ugric theory only speaks to the origin of the Hungarian language, not other parts of the ancient Hungarians’ history and culture properly addressed by archeology, history, or, most recently, genetics (10).

What about religion? Does it play a role?

Hungarians converted to Roman Christianity when they settled down in the 11th century, were swept by the Reformation in the 16th, and then largely reconverted to Catholicism under the Hapsburgs. Today the majority identify as Christian, but religiosity is low (as is the case in most of the former Soviet bloc with the exception of Poland). Most of the minority who are strongly religious are Roman Catholic and have not been influenced much by the science vs. the Bible controversies of American evangelicalism.

None of this religious landscape plays a role in Hungarians’ view of the Finno-Ugric affiliation of their language. For those who reject it, their attitude springs from deeply held beliefs, but these beliefs have nothing to do with religion. There’s no scriptural interpretation or doctrine of salvation that needs to be defended from Finno-Ugric linguistics.

What this strange case of denialism demonstrates, I believe, is the role of traditions that are superficially understood but strongly held against perceived threats from outside, and the way deeply ingrained cultural inferiority complexes can fuel such responses. Education and better explanations of the science rarely make a dent in such cases unless the perception of threat is addressed through other means, and accepting the scientific consensus becomes emotionally possible and culturally acceptable. I think that’s likely true for the scientific controversies plaguing American Christianity as well. How to bring about such change is not something I can answer, but the conversation among Christians should certainly be characterized by patience, kindness, and grace as we speak the truth in love (Eph. 4:15).

References

1. Chris Mooney: “These Charts finally explain where science denialism comes from.” The Washington Post, Nov 11, 2014. Accessed 10/15/2023. Link

2. Stephen R. Anderson: “How many languages are there in the world?” Linguistic Society of America. Link

3. “Indo-European languages.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation. Last edited 11/11/2023. Link

4. Harms, Robert Thomas. "Uralic languages". Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Sep. 2023, Link

5. “Linguistic map of the Uralic languages.” Wikimedia Commons. Created by User:Nug derived from a German version created by User:Chumwa, 11/20/2013. Link

6. “Filius.” Wiktionary, Wikimedia Foundation. Last edited 8/23/2023 Link

7. For those interested in more details, the Wikipedia entry on the comparative method is a good summary: Link

8. “Uralonet entry 228: kala.” Research Institute for Linguistics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Link

9. Table based on Uralonet entries 829, 729, 695, 739, 722, 812, 767, 740, and 830. Link

10. Johanna Laakso. "Interpretations and Misinterpretations of Finno-Ugric relatedness." Paper presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of Societas Linguistica Europaea (http://sle2012.eu/), Stockholm, August 2012. Link

Anikó Albert grew up in Budapest, Hungary, and is a graduate of Eötvös Loránd University. A serial migrant, she taught English as a Foreign Language in her hometown, high-school Spanish in Kingston, Jamaica, and English and various subjects in Alameda, California. She is currently the Managing Editor of God and Nature, and Chair of Rockville Help, an emergency assistance charitable organization in Rockville, Maryland.

As is often noted, there are some interesting parallels between historical comparative linguistics and evolution. Both involve descent with modification from a common ancestor over long periods of time—much shorter in the case of languages, but still beyond what the human mind can intuitively grasp. In both cases, understanding how small changes can add up over time to lead to something very different and new requires some education, so it would make sense that people might struggle with both concepts.

But Finns, Estonians, and speakers of the many Uralic minority languages in Russia have no doubts about their languages being part of the Uralic family together with Hungarian. Denying this well-established fact is unique to Hungarians. Why? What is driving this strange form of denialism? There are several possible factors.

One of them is straightforward and stands out on the map: the other Uralic languages have relatives near them, while Hungarian is far away, and on its own. As a result of this distance, Hungarian has no close relatives—no language with which the relationship is obvious and some mutual intelligibility exists. The experience that Finns have with Estonians (or Italians with Spaniards, Slavic speakers with each other, etc.) is one Hungarians never get to share. It’s perhaps easier to imagine that one’s language is something completely different in this situation.

But the main stumbling block is historical. Back in the 19th century, when the Finno-Ugric theory first rose to general attention in in Hungary, the country was under Hapsburg rule. There had been several defeated uprisings, and before all that, occupation by the Ottoman Empire. Hungarians had not been independent for several centuries, and as people often do in such situations, they were holding on fast to stories of a mythologized, glorious past. But the Finno-Ugric relatives the linguists were proposing were nothing like the Hungarian heroes of old were supposed to be—they were not the skilled horsemen of legend whose arrows western Europe feared in the 10th century. They mostly lived in cold places way up north and were humble farmers, fishermen, or reindeer herders. And they had no countries of their own either. They were no help to flailing national pride.

So a conspiracy theory quickly took hold: one of those linguist guys is German, so “Finno-Ugrism” must be an evil Hapsburg plot to break the Hungarian spirit! Over time, the theory could be adjusted and projected onto anyone suspected of wanting to keep Hungarians down—the Russians were thought to be “pushing” Finno-Ugric linguistics during the Soviet occupation, even though they weren’t (they had little interest in fostering a pan-Uralic identity among minorities in the Soviet Union). Alternative “theories” have abounded over the years and ranged from the plausible but wrong (a relationship with Turkic languages instead) to the pseudo-historical or insane (Sumerians, aliens from Sirius, etc.) Many of them persist today even though modern linguists emphasize that the Finno-Ugric theory only speaks to the origin of the Hungarian language, not other parts of the ancient Hungarians’ history and culture properly addressed by archeology, history, or, most recently, genetics (10).

What about religion? Does it play a role?

Hungarians converted to Roman Christianity when they settled down in the 11th century, were swept by the Reformation in the 16th, and then largely reconverted to Catholicism under the Hapsburgs. Today the majority identify as Christian, but religiosity is low (as is the case in most of the former Soviet bloc with the exception of Poland). Most of the minority who are strongly religious are Roman Catholic and have not been influenced much by the science vs. the Bible controversies of American evangelicalism.

None of this religious landscape plays a role in Hungarians’ view of the Finno-Ugric affiliation of their language. For those who reject it, their attitude springs from deeply held beliefs, but these beliefs have nothing to do with religion. There’s no scriptural interpretation or doctrine of salvation that needs to be defended from Finno-Ugric linguistics.

What this strange case of denialism demonstrates, I believe, is the role of traditions that are superficially understood but strongly held against perceived threats from outside, and the way deeply ingrained cultural inferiority complexes can fuel such responses. Education and better explanations of the science rarely make a dent in such cases unless the perception of threat is addressed through other means, and accepting the scientific consensus becomes emotionally possible and culturally acceptable. I think that’s likely true for the scientific controversies plaguing American Christianity as well. How to bring about such change is not something I can answer, but the conversation among Christians should certainly be characterized by patience, kindness, and grace as we speak the truth in love (Eph. 4:15).

References

1. Chris Mooney: “These Charts finally explain where science denialism comes from.” The Washington Post, Nov 11, 2014. Accessed 10/15/2023. Link

2. Stephen R. Anderson: “How many languages are there in the world?” Linguistic Society of America. Link

3. “Indo-European languages.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation. Last edited 11/11/2023. Link

4. Harms, Robert Thomas. "Uralic languages". Encyclopedia Britannica, 21 Sep. 2023, Link

5. “Linguistic map of the Uralic languages.” Wikimedia Commons. Created by User:Nug derived from a German version created by User:Chumwa, 11/20/2013. Link

6. “Filius.” Wiktionary, Wikimedia Foundation. Last edited 8/23/2023 Link

7. For those interested in more details, the Wikipedia entry on the comparative method is a good summary: Link

8. “Uralonet entry 228: kala.” Research Institute for Linguistics, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Link

9. Table based on Uralonet entries 829, 729, 695, 739, 722, 812, 767, 740, and 830. Link

10. Johanna Laakso. "Interpretations and Misinterpretations of Finno-Ugric relatedness." Paper presented at the 45th Annual Meeting of Societas Linguistica Europaea (http://sle2012.eu/), Stockholm, August 2012. Link

Anikó Albert grew up in Budapest, Hungary, and is a graduate of Eötvös Loránd University. A serial migrant, she taught English as a Foreign Language in her hometown, high-school Spanish in Kingston, Jamaica, and English and various subjects in Alameda, California. She is currently the Managing Editor of God and Nature, and Chair of Rockville Help, an emergency assistance charitable organization in Rockville, Maryland.