Is there Hope for the Ocean?

Loggerhead sea turtle swimming

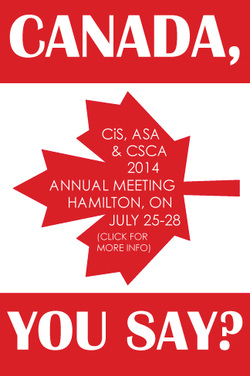

by Bob Sluka

Threats to marine life A trip to the beach reveals tide pools full of interesting creatures. A storm rolls in and we see the power of the waves pounding the beach. There are still many places in the world where we can revel in God’s beauty, majesty and creative power in, at, or around the ocean[i]. However, the ocean is a shadow of its former self. Research suggests that fish are less abundant, waters polluted, ecosystems lost or changed beyond recognition, seas of trash float around, and physical and chemical changes threaten some species’ survival. An exhaustive list of threats to our oceans would be overwhelming[ii], so I want to focus here on a few of the major problems: overfishing, climate change, and land-based impacts such as pollution. There is a natural rate of reproduction for most fish and other sea creatures, which is often exponentially related to their size. Fishing tends to target the larger individuals of a species, which are also the ones that produce the most offspring. For example, catching one large grouper of about a meter in size could be the same as removing hundreds of individuals half that size in terms of how many eggs they might produce (Sluka et al 1997). In fact, in the case of groupers their biology complicates things even more in that most of the commercially caught grouper species start out life as females and then turn into males as they grow in size and have reproduced several times as a female. So by targeting the larger individuals in the population, a huge proportion of the males are removed, in some cases so many that not enough are left for successful reproduction. Most of these grouper species gather in what used to be very large numbers at very specific places and times of the year to spawn. Fishermen have naturally targeted these aggregations, and it doesn’t take a research scientist to understand that this has huge impacts on the population. There are many definitions of overfishing, but a simple one is when fishing occurs at a level which reduces the quantity and quality of target organisms such that it endangers future exploitation. An example of a fishing method that tends towards overfishing would be bottom trawling. The trawl net is essentially a bag pulled through the water catching everything in its path. There is usually a heavy beam attached to the mouth of the net to keep the net open. By dragging this across the bottom to scoop up fish or shrimp, sessile organisms such as corals and sponges are destroyed. These habitats no longer provide shelter for smaller fish which now experience more predation, and there can be a large number of unwanted organisms (called bycatch) caught along with the target species. The end results are a decline in the number and size of the target population, declines in bycatch species and destruction of the habitat. This can cause shifts in ecosystem structure and function. Research suggests that the global impact of climate change on marine ecosystems is likely to be dramatic. In the tropics, coral reefs are under threat from warmer water and ocean acidification, both at least partially attributable to human-induced climate change. Fish populations in the US (and elsewhere) are shifting their distributions to seek out water of preferred temperatures. Coastal land is threatened by sea level rise. A global assessment of anthropogenic threats to marine ecosystems identifies multiple threats in every case. However, the authors were surprised that most of the greatest threats in their analysis were from land-based activities, including climate change. “There is the sea, vast and spacious, teeming with creatures beyond number – living things both large and small” (Psalm 104:25). Yet, what we do on land dramatically impacts the ocean. We build a golf course next to the ocean that needs fertilizers to keep the greens green. With the next rain it is washed off into the sea where algae are able to utilize it to outcompete corals, in some cases shifting the systems from coral reefs to algal forests. A plastic bag is washed into the sea on a beach picnic in California and ends up circulating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean (the so-called “Great Pacific Garbage Patch”) or washes up on a beach in a South Pacific island or perhaps worse, is mistaken for a jellyfish by a sea turtle, ingested and causes injury or death to these animals. As an aside, one of the most poignant marine conservation dramas I have witnessed was when my daughter’s fourth grade class did a dance of the sea turtles complete with jellyfish being eaten and then one child acting as a plastic bag. Watching the turtle “eat” the plastic bag child and then die choking was heart-rendingly horrendous, but hugely powerful. I will likely never bring a plastic bag to the seaside again. We have seen with our greenhouse gas emissions, what we do on the land impacts the sea. Through ocean currents what we do to the sea in one place can be transported to other far distant places where these problems did not originate. Ultimately, we are not loving our neighbours, but doing to them as we would not want them to do to us. Hope for the Ocean Is there hope? I believe so. Our ultimate hope, of course, is in the one through whom and for whom all things were created, but there are also things we can do. While we have to exercise appropriate humility in our dealing with the ocean[iii], we do know some things that we can do to glorify God through caring for the ocean. Fisheries are managed by limiting the amount of the target species caught or their size, allowing individuals to reproduce before capture. Management can also take the form of limiting effort. For example, allowing only certain sized boats or regulating net mesh size so that small fish pass through. There is important work here for fisheries scientists, mathematicians, biologists and ecologists who can study the target species and the fishing techniques and determine the appropriate quantities to harvest and sustainable techniques. The world needs Christians in these fields who can, as Psalm 111:1-2 exhorts, delight in and study the works of God. Many of us are familiar with national parks on land. You may be surprised to know that there is a growing network of these in the sea. Variously named, these marine protected areas[iv] have regulations that seek to limit the damage to the ecosystems under protection. While marine protected areas, like national parks, cannot exist in a vacuum as islands of biodiversity with the surrounding area decimated by uncontrolled activities, they have proven successful in both protecting biodiversity and enhancing fisheries. It is counterintuitive that closing an area to fishing increases catch for fishermen, but within several years, depending on the state of the area prior to closing, the activities outside the reserve, and enforcement, fishermen near the reserve see their catches generally increase. This is due to the biology of most sea creatures as noted above – the abundance of the park overflows into the surrounding areas reminiscent of the teeming and swarming and original blessing of the sea (Genesis 1:22). Climate change is and will have huge impacts on the ocean. So anything that is done to reduce the drivers of climate change is, in fact, marine conservation. Are you working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions? Then you are doing marine conservation. Most of us know that forests store carbon and help to sequester carbon dioxide (that is, remove CO2 from the atmosphere). Similarly, mangrove forests and seagrass beds do the same. Activities which increase the area of mangrove forests or seagrass beds, such as planting programmes or which seek to stop the destruction of these habitats, are contributing to mitigating the impacts of climate change drivers. Pollution is an area where we can have a huge impact. A beach or coast clean-up is a great activity to enjoy the outdoors. Gather a group of friends or have your church picnic at the coast and spend even 30 minutes with a rubbish bag picking up what shouldn’t be there. Your neighbours will thank you. A Rocha Kenya Marine Conservation and Research Programme One example of a Christian program focussed on this topic is the Marine Conservation and Research Programme of A Rocha Kenya (ARK)[v] and the growing marine conservation work of A Rocha globally. The ARK field study centre in Kenya is located on the shore of Watamu Marine National Park. This is a marine protected area with globally rare or threatened marine biodiversity. Researchers are studying biodiversity, the impact of tourism on coral reefs, climate change issues, and beginning community outreach and education among fishermen focused on poverty alleviation. This is done in partnership with government management of the park and community organizations. A training program has been set up for local and international volunteers and interns so that they can learn important marine research methods and concepts, living in a Christian community that invites people of all faith backgrounds to come and see. Theological Resources I and others (such as the Faraday Institute at Cambridge University) are working together to develop new and make known previously available resources that help us to think Biblically about the ocean and marine conservation. You can find these resources by emailing me or online through A Rocha Kenya’s marine research and conservation program where we are trying to implement many of these principles. There you will find resources, including an inductive Bible study, which will help you contemplate these issues. Our trust is in our Lord who created the oceans and in whom is ultimately our hope for the oceans. [i] The starting point for much of this text is from a Grove Booklet by Robert Sluka entitled Hope for the Ocean: Marine Conservation, poverty alleviation, and blessing the nations available at http://www.grovebooks.co.uk/cart.php?target=product&product_id=17558 and a forthcoming article by Meric Srokoz and myself entitled Creation care in the other 71% which is being published as part of the Lausanne Movements’ Gospel and Creation Care book. [ii] for a recent synopsis start with Halpern, B.S., Selkoe, K.A., Micheli, F. & Cappel, C.V. (2007), ‘Evaluating and ranking the vulnerability of global marine ecosystems to anthropogenic threats’, Conservation Biology 21:1301-15. [iii] S P Bratton, ‘The precautionary principle and the book of Proverbs: Toward an ethic of ecological prudence in ocean management’ Worldviews (2003) 7(3), 252-273 and R Sluka (2012) Hope for the Ocean: Marine Conservation, Poverty Alleviation and Blessing the Nations. Grove Booklets. 28pp. [iv] For a recent synthesis of this topic see S E Lester, B S Halpern, K Grorud-Colvert, J Lubchenco, B I Ruttenberg, S D Gaines, S Airame, and R R Warner, ‘Biological effects within no-take marine reserves: a global synthesis’ Marine Ecology Progress Series (2009) 384, 33-46. [v] http://www.arocha.org/ke-en/work/research/marine |