God and Nature Winter 2019

by Lydia Marcus

According to a recent Pew Research Center poll, 53% of the U.S. population say that science and religion are often in conflict (1). This percentage is only slightly lower in strongly religious communities. Among U.S. adults who attend church at least weekly, 48% say that science and religion are often in conflict. Many Christians in the sciences find this trend deeply troubling, and they are eager to ease the apparent tension between science and religion. To effectively challenge the conflict model of the relationship between science and religion, it is useful to first understand why people might default to a conflict model. Qualitative research in this area supplements the quantitative statistics with insights into individuals' opinions. I will draw on this body of research to develop a case for why people may be inclined to see conflict between religion and science, and how we can help them resolve the perceived tension.

According to a recent Pew Research Center poll, 53% of the U.S. population say that science and religion are often in conflict (1). This percentage is only slightly lower in strongly religious communities. Among U.S. adults who attend church at least weekly, 48% say that science and religion are often in conflict. Many Christians in the sciences find this trend deeply troubling, and they are eager to ease the apparent tension between science and religion. To effectively challenge the conflict model of the relationship between science and religion, it is useful to first understand why people might default to a conflict model. Qualitative research in this area supplements the quantitative statistics with insights into individuals' opinions. I will draw on this body of research to develop a case for why people may be inclined to see conflict between religion and science, and how we can help them resolve the perceived tension.

"If we witness Christians who both live Christ-like lives and accept the theory of evolution, our assumption that good Christians must reject evolution starts to crumble." |

Scientific Literacy and Social Identity Influence a Person’s Perspective

Undoubtedly, many factors contribute to a person’s acceptance or rejection of the conflict model, but one’s scientific literacy and one’s social identity seem to be two prominent ones (2,3). Science is often perceived as inaccessible to laypeople, especially by those who are not scientifically literate. Scientists typically speak about science using technical and heavily nuanced vocabulary (e.g. the word “theory” tends to mean “untrustworthy hunch” in everyday parlance, but it typically means “well-validated and trustworthy description of reality” when used in scientific literature). This specialized use of language, combined with the apparently counterintuitive nature of certain scientific theories, can make scientifically illiterate laypeople more inclined to trust science popularizers or science denialists — who tend to be more obviously convinced of what is true and are disproportionately represented in the media (4) — than they are to trust actual scientists.

In addition, a person’s social circle influences how she or he views science. We are inclined to adopt the opinions of the people who are prominent in our perceived ingroup (5). In the case of the American Christian community, the members who seem to be the most vocal about their opinions regarding science (particularly the creation of the world) and their faith tend to be the ones who have heartily rejected the theory of evolution. So, almost by default, some Christians reject certain aspects of modern science because prominent Christians have proclaimed that that type of science is an affront to their faith. Most lay people will not regularly need to defend their perspective on the relationship between modern science and their faith, so forming opinions based on what science popularizers and vocal Christians say is often sufficient for them.

Sometimes, human psychology seems to predispose us to be disinclined to assimilate certain scientific theories. Some science, such as the theory of evolution, seems downright counterintuitive. Humanity seems to be naturally inclined to look for agency everywhere (6) and to understand things in terms of their teleological “essence” (7), but the theory of evolution does not itself provide a description of who causes evolution, and it challenges the idea that things have unchangeable essences. Even medical students who are undoubtedly familiar with the basic principles of evolution are apparently more inclined to affirm a Lamarckian understanding of evolution rather than a Darwinian one, perhaps because a Lamarckian understanding aligns with our desire for teleological functionality more readily (8,9).

Young children are especially prone to understand the world in terms of essences and teleology, and studies have shown that – regardless of the child’s parents’ beliefs about evolution or creationism – children prefer some form of creationism over evolution (10). A creationist account such as the one supplied by a literal interpretation of the first chapters of Genesis fits more readily with the way we prefer to understand the world, and it takes a fair amount of conscious effort to overcome this bias toward teleology if one wants to accept the theory of evolution. For most laypeople, it truly is simpler to just accept an account of origins that fits with our natural psychological biases.

Moreover, adopting a creationist perspective on the origin of life reaffirms a Christian’s social identity because the creationist perspective aligns nicely with what appears to be The Christian Position on the origin of life (based on how well the anti-evolution Christians advertise their opinion). Social identity is important to people, and choosing to hold the same opinion as one’s ingroup is a simple way to ingratiate oneself with the ingroup and separate oneself from the outgroup (5). For example, Christians might use political platforms, Sunday dress codes, and open condemnation of evolution as ways of differentiating themselves from non-Christians. Sometimes, these means of differentiation are good and wise; other times, our means of differentiation are dangerously under-analyzed and consequently fairly un-Christian.

The pressure to adopt one’s Christian ingroup’s view of the world discourages people from accepting the reality of things such as the theory of evolution and climate change; entertaining a dissenting opinion makes you feel like a heretic, even if you honestly believe that your opinion is fully compatible with obedience to God.

Though I empathize with people’s desire to be Christian in all of their beliefs, rejecting the theory of evolution and “secular science” by default is rather irresponsible and potentially disastrous. Seventy-eight percent of Americans who now identify as atheistic, agnostic, or unreligious grew up in religious homes, and one of the most common topics people cite as the reason that they abandoned their faith is the apparent conflict between their faith and modern science (most commonly, the theory of evolution and the origin of the universe) (1). Rejecting parts of modern science may be simpler and helpful for one’s social identity, but it can also needlessly drive people away from Christianity.

Intentional Discourse Can Prevent Acceptance of Conflict Model

Disabusing people of the assumption that modern science and Christianity are necessarily in conflict is difficult. But if we recognize why people may be inclined to believe that the two conflict, we can intentionally address their misconceptions more effectively. Research suggests that both observing Christian role models who accept evolution and recognizing that a person’s salvation is not dependent on his or her acceptance or denial of evolution are key to a Christian college student’s ability to make peace between his or her faith and the theory of evolution (2).

These findings make a lot of sense. If we witness Christians who both live Christ-like lives and accept the theory of evolution, our assumption that good Christians must reject evolution starts to crumble. Other research has indicated that getting students to critically examine why they believe what they believe and how they reason about issues helps people to better understand what science actually says, and thus assimilate scientific theories more readily (3).

Undoubtedly, many factors contribute to a person’s acceptance or rejection of the conflict model, but one’s scientific literacy and one’s social identity seem to be two prominent ones (2,3). Science is often perceived as inaccessible to laypeople, especially by those who are not scientifically literate. Scientists typically speak about science using technical and heavily nuanced vocabulary (e.g. the word “theory” tends to mean “untrustworthy hunch” in everyday parlance, but it typically means “well-validated and trustworthy description of reality” when used in scientific literature). This specialized use of language, combined with the apparently counterintuitive nature of certain scientific theories, can make scientifically illiterate laypeople more inclined to trust science popularizers or science denialists — who tend to be more obviously convinced of what is true and are disproportionately represented in the media (4) — than they are to trust actual scientists.

In addition, a person’s social circle influences how she or he views science. We are inclined to adopt the opinions of the people who are prominent in our perceived ingroup (5). In the case of the American Christian community, the members who seem to be the most vocal about their opinions regarding science (particularly the creation of the world) and their faith tend to be the ones who have heartily rejected the theory of evolution. So, almost by default, some Christians reject certain aspects of modern science because prominent Christians have proclaimed that that type of science is an affront to their faith. Most lay people will not regularly need to defend their perspective on the relationship between modern science and their faith, so forming opinions based on what science popularizers and vocal Christians say is often sufficient for them.

Sometimes, human psychology seems to predispose us to be disinclined to assimilate certain scientific theories. Some science, such as the theory of evolution, seems downright counterintuitive. Humanity seems to be naturally inclined to look for agency everywhere (6) and to understand things in terms of their teleological “essence” (7), but the theory of evolution does not itself provide a description of who causes evolution, and it challenges the idea that things have unchangeable essences. Even medical students who are undoubtedly familiar with the basic principles of evolution are apparently more inclined to affirm a Lamarckian understanding of evolution rather than a Darwinian one, perhaps because a Lamarckian understanding aligns with our desire for teleological functionality more readily (8,9).

Young children are especially prone to understand the world in terms of essences and teleology, and studies have shown that – regardless of the child’s parents’ beliefs about evolution or creationism – children prefer some form of creationism over evolution (10). A creationist account such as the one supplied by a literal interpretation of the first chapters of Genesis fits more readily with the way we prefer to understand the world, and it takes a fair amount of conscious effort to overcome this bias toward teleology if one wants to accept the theory of evolution. For most laypeople, it truly is simpler to just accept an account of origins that fits with our natural psychological biases.

Moreover, adopting a creationist perspective on the origin of life reaffirms a Christian’s social identity because the creationist perspective aligns nicely with what appears to be The Christian Position on the origin of life (based on how well the anti-evolution Christians advertise their opinion). Social identity is important to people, and choosing to hold the same opinion as one’s ingroup is a simple way to ingratiate oneself with the ingroup and separate oneself from the outgroup (5). For example, Christians might use political platforms, Sunday dress codes, and open condemnation of evolution as ways of differentiating themselves from non-Christians. Sometimes, these means of differentiation are good and wise; other times, our means of differentiation are dangerously under-analyzed and consequently fairly un-Christian.

The pressure to adopt one’s Christian ingroup’s view of the world discourages people from accepting the reality of things such as the theory of evolution and climate change; entertaining a dissenting opinion makes you feel like a heretic, even if you honestly believe that your opinion is fully compatible with obedience to God.

Though I empathize with people’s desire to be Christian in all of their beliefs, rejecting the theory of evolution and “secular science” by default is rather irresponsible and potentially disastrous. Seventy-eight percent of Americans who now identify as atheistic, agnostic, or unreligious grew up in religious homes, and one of the most common topics people cite as the reason that they abandoned their faith is the apparent conflict between their faith and modern science (most commonly, the theory of evolution and the origin of the universe) (1). Rejecting parts of modern science may be simpler and helpful for one’s social identity, but it can also needlessly drive people away from Christianity.

Intentional Discourse Can Prevent Acceptance of Conflict Model

Disabusing people of the assumption that modern science and Christianity are necessarily in conflict is difficult. But if we recognize why people may be inclined to believe that the two conflict, we can intentionally address their misconceptions more effectively. Research suggests that both observing Christian role models who accept evolution and recognizing that a person’s salvation is not dependent on his or her acceptance or denial of evolution are key to a Christian college student’s ability to make peace between his or her faith and the theory of evolution (2).

These findings make a lot of sense. If we witness Christians who both live Christ-like lives and accept the theory of evolution, our assumption that good Christians must reject evolution starts to crumble. Other research has indicated that getting students to critically examine why they believe what they believe and how they reason about issues helps people to better understand what science actually says, and thus assimilate scientific theories more readily (3).

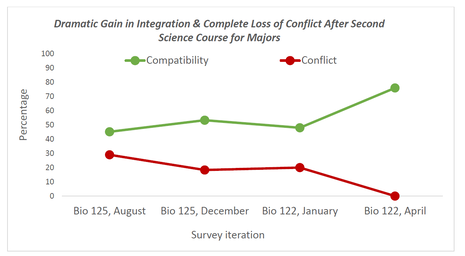

Some science professors (both Christian and non-Christian, like atheist Elizabeth Barnes) strive to implement these ideas in their classes so that young adults have an opportunity to reconcile their faith and science, and consequently gain improved scientific literacy and possibly even a more mature faith. And their efforts seem to be fruitful (2,11,12). For example, Dordt College science professors intentionally cultivate relationships with their students and incorporate healthy discussions about science and Christianity into their courses. Survey data suggest that Dordt students were much more likely to perceive science and their faith as compatible after taking a year’s worth of biology classes than they were at the start of the year (Figure 1) (12). In fact, the percentage of students in the second semester biology class (Bio 122, Zoology) who claimed to see conflict between science and their faith decreased from 20% to 0% over the course of the semester. Student responses to the short-answer portion of the survey indicate that students felt more at liberty to critically examine the relationship between their faith and science after prolonged interaction with their Christian science professors.

Though it can be difficult for students who don’t study science at a Christian university to get exposure to intentional discussions about science and Christianity, the number of resources available to young people who are wondering about the relationship between science and their faith is steadily increasing. For example, the John Templeton Foundation and Fuller Seminary recently funded a grant, called the STEAM Project, that aims to “catalyze the integration of Christian faith and science” for young adults.

Figure 1

This grant funded the projects of more than 30 groups across North America, who spent two years developing ways to help people learn to see compatibility between science and faith. Some people created videos that addressed topics such as the imago Dei in light of human evolution; others invited scientists to speak about their professions at a local church. I was part of a group at Dordt College that produced two dozen small-group discussion guides about a range of science and faith topics in an effort to provide people with a means of developing a community in which they could think through big questions (12). Organizations such as Scientists in Congregations, BioLogos, and the Ian Ramsey Center have been pondering the relationship between science and faith for many years. There are wise, intelligent people doing good work in the area of science and religion—it’s largely a matter of knowing where to look.

References

1. Masci, D. (2009, November 5). Public Opinion on Religion and Science in the United States. Pew Research Centers Religion Public Life. Retrieved April 20, 2016, from http://www.pewforum.org/2009/11/05/public-opinion-on-religion-and-science-in-the-united-states/

2. Winslow, M. (2011, April 29). Evolution and personal religious belief: Christian biology-related majors' search for reconciliation at a Christian university. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(9), 1026-1049. doi:10.1002/tea.20417

3. Sinatra, G., Kienhues, D., & Hofer, B. (2014). Addressing Challenges to Public Understanding of Science: Epistemic Cognition, Motivated Reasoning, and Conceptual Change. Educational Psychologist, 1-16.

4. Glover, M. (2010). Global Warming - The Debate. Renegade Conservatory Guy.

5. Turner, J. C., & Tajfel, H. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of intergroup relations, 7-24.

6. Gergely, G., & Csibra, G. (2003). Teleological reasoning in infancy: the naive theory of rational action. Trends in Cognitive Science, 287-292.

7. Kelemen, D. (1999). The scope of teleological thinking in preschool children. Cognition, 241-272.

8. Brumby, M. (1984). Misconceptions about the concept of natural selection by medical biology students. Science Education, 493-503.

9. Evans, E. M. (2001). Cognitive and contextual factors in the emergence of diverse belief systems: creation versus evolution. Cognitive Psychology, 217-266.

10. Evans, E. M. (2000). The emergence of beliefs about the origins of species in school-age children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 221-254.

11. Barnes, M. E., Elser, J., & Brownell, S. (2017, February 2). Impact of a Short Evolution Module on Students' Perceived Conflict between Religion and Evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 104-111. Retrieved from http://abt.ucpress.edu/content/79/2/104

12. Marcus, L., & Eppinga, R. (2017). Measuring Faith and Science Perspectival Development in Undergraduates at Dordt College. Sioux Center: Dordt College.

Lydia Marcus graduated with a B.S. in biology from Dordt College in 2017 and is currently pursuing a MPH in epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee. She's interested in breast cancer epidemiology and studying how social disparities influence health inequalities. In her free time, she reads, thinks, and writes about the relationship between faith and science.

Though it can be difficult for students who don’t study science at a Christian university to get exposure to intentional discussions about science and Christianity, the number of resources available to young people who are wondering about the relationship between science and their faith is steadily increasing. For example, the John Templeton Foundation and Fuller Seminary recently funded a grant, called the STEAM Project, that aims to “catalyze the integration of Christian faith and science” for young adults.

Figure 1

This grant funded the projects of more than 30 groups across North America, who spent two years developing ways to help people learn to see compatibility between science and faith. Some people created videos that addressed topics such as the imago Dei in light of human evolution; others invited scientists to speak about their professions at a local church. I was part of a group at Dordt College that produced two dozen small-group discussion guides about a range of science and faith topics in an effort to provide people with a means of developing a community in which they could think through big questions (12). Organizations such as Scientists in Congregations, BioLogos, and the Ian Ramsey Center have been pondering the relationship between science and faith for many years. There are wise, intelligent people doing good work in the area of science and religion—it’s largely a matter of knowing where to look.

References

1. Masci, D. (2009, November 5). Public Opinion on Religion and Science in the United States. Pew Research Centers Religion Public Life. Retrieved April 20, 2016, from http://www.pewforum.org/2009/11/05/public-opinion-on-religion-and-science-in-the-united-states/

2. Winslow, M. (2011, April 29). Evolution and personal religious belief: Christian biology-related majors' search for reconciliation at a Christian university. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(9), 1026-1049. doi:10.1002/tea.20417

3. Sinatra, G., Kienhues, D., & Hofer, B. (2014). Addressing Challenges to Public Understanding of Science: Epistemic Cognition, Motivated Reasoning, and Conceptual Change. Educational Psychologist, 1-16.

4. Glover, M. (2010). Global Warming - The Debate. Renegade Conservatory Guy.

5. Turner, J. C., & Tajfel, H. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychology of intergroup relations, 7-24.

6. Gergely, G., & Csibra, G. (2003). Teleological reasoning in infancy: the naive theory of rational action. Trends in Cognitive Science, 287-292.

7. Kelemen, D. (1999). The scope of teleological thinking in preschool children. Cognition, 241-272.

8. Brumby, M. (1984). Misconceptions about the concept of natural selection by medical biology students. Science Education, 493-503.

9. Evans, E. M. (2001). Cognitive and contextual factors in the emergence of diverse belief systems: creation versus evolution. Cognitive Psychology, 217-266.

10. Evans, E. M. (2000). The emergence of beliefs about the origins of species in school-age children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 221-254.

11. Barnes, M. E., Elser, J., & Brownell, S. (2017, February 2). Impact of a Short Evolution Module on Students' Perceived Conflict between Religion and Evolution. The American Biology Teacher, 104-111. Retrieved from http://abt.ucpress.edu/content/79/2/104

12. Marcus, L., & Eppinga, R. (2017). Measuring Faith and Science Perspectival Development in Undergraduates at Dordt College. Sioux Center: Dordt College.

Lydia Marcus graduated with a B.S. in biology from Dordt College in 2017 and is currently pursuing a MPH in epidemiology at the University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee. She's interested in breast cancer epidemiology and studying how social disparities influence health inequalities. In her free time, she reads, thinks, and writes about the relationship between faith and science.