I Sleep A Lot

by Denis O. Lamoureux

“Can you prove to me that the resurrection actually happened?” This was the very first question that was launched at me in September 1997, during the first minute of my first class teaching Science and Religion at St. Joseph’s College, University of Alberta. Of course, the question caught me off guard, because it was completely out of context. I mumbled and stumbled and can’t remember what I said. But I do recall thinking to myself that if this is what teaching theology is going to be like, then I wanted to cross the street and return to the Faculty of Dentistry where I had been a clinical instructor for previous six years. Teaching students how to pull teeth is a lot easier! Fifteen years later, I’m sitting in a campus pub across from the student who asked that very first question, sharing a good laugh about how my theological teaching career began. This is one of the most blessed aspects of being a university professor. A number of our students become life-long friends. Not only that, the irony of teaching such talented young men and women is that they end up teaching professors as much as their professors teach them. In that inaugural class, I knew intuitively that this young man was special. And indeed he was. He was incredibly bright and was being pursued by the university to go to graduate school in his specialized scientific discipline. But instead he went off to seminary to study theology. There were more pressing and larger questions that needed to be answered. Eventually the reality of having to make a living caught up to him. He became a very successful businessman, making six figures a year and working only a few hours a week. Yet as the theme of the Book of Ecclesiastes reveals, he has come to see the vanity of it all. And he reminds me that I predicted he would return to the academy, because it’s the pursuit of those questions about the meaning of life that beacon the human soul. Sure enough, here we were, sitting in a campus pub (where so many important decisions are made), and he was exploring the possibility of graduate school in philosophy. And then in midst of our conversation, he said it. “I sleep a lot.” For most people, these four words mean very little. But for me, they shout out. It’s because I suffer from depression, and the classic sign of this medical condition is that patients sleep a lot. Cautiously, I asked him more about why he slept so much. I revealed to him that this was the main symptom that led to my diagnosis. As he slowly opened this dark region of his life, I felt comfortable asking another question, one that few of us ask our friends. “Ever think about ending it all?” Yes, the “s” word. The word no one wants to talk about, let alone admit having pondered seriously, especially if you are a Christian. I further disclosed that I had thought about suicide before, and often yearned that my life would end. In fact, I knew exactly what I would write on the suicide note. “I’m tired of being tired.” But despite the power of these feelings, taking my life was only a thought and never a reality. My faith was my rock. I knew well that if I ever took my life, I would soon be standing in front of Jesus with absolutely no excuse. Besides, I could not do that to those I love—my family, my friends, and my students, like this former student in front of me. And then I said to him, what I believe needs to be said from the pulpit in every church. “It’s OK to get psychiatric help; and it’s OK to use medication. It’s not against God’s will.” One of the most enlightening aspects of being treated for depression is that a doctor takes an inventory of your life. It’s here where I realized that for years I have been doing things that are not healthy for my brain. Though there is a history of depression in my family that few ever talked about, the primary etiological factor of my condition was that I simply had not taken time off from school/work. In graduate school, I did two masters degrees in 24 months and two doctoral degrees in 80 months. To finance my education I practiced dentistry. So I went from the library or laboratory to the dental clinic and back again without any holidays, assuming that a change was as good as break. Wrong. The chronic stress in both grad school and dental practice are well-known. My brain needed a break. And since beginning my teaching career in 1997, I had never taken a holiday. I’d assumed that going to a conference like the annual American Scientific Affiliation meeting was the same as a break. Wrong again. As much as I love being with my pals like Terry Gray, Paul Seely, and Kirk Bertsche, we spend most of our time debating the issues of science and religion. And with these guys, you’ve got to be at your academically best … or else! The greatest revelation of my psychiatric evaluation was identifying my weekly habits. I’ll admit there’s a bit of righteous pride in saying I work for six days and then take Sunday off. But is Sunday really a day off for me? It’s not. I might be sitting quietly in a pew listening, but my brain is in overdrive thinking theologically. Where this became painfully evident was when I looked at my written notes for my book Evolutionary Creation (2008). I have pages upon pages of stapled offering envelopes from my church with penciled-in ideas for the book. And this is a problem for many of us in ministry. Sunday is not a day off and we need to find a day to rest both our soul and our brain. So here is the bottom line: I started graduate school in September 1984, and up until about two years ago, I haven’t taken a real holiday or observed the Sabbath in any restful way. Something had to snap. But depression is not like a broken leg. Many times, it slowly creeps up on you. There isn’t a day when I can say “I became depressed.” I knew I was tired when I finished graduate school, but just thought that was normal, and assumed it would go away. But it didn’t. The stress also continued; first in establishing the first tenure-track position for Science and Religion in Canada, and then competing for tenure in a research university. Sleeping during the day began around this time. It started with a 20-minute nap at lunch. Then it extended to an hour, then two hours, and then up to four hours. That and I was sleeping eight to nine hours at night. The breaking point came when I started to sleep for an hour after supper. That hit me hard. I knew that there was something terribly wrong. My parents are in their mid-80s and they only needed a one-hour nap after lunch. But I was in my mid-50s and I needed to sleep twice a day to function. Even after all this sleeping, I still felt tired. So how did I end up in the psychiatrist’s office? It was the personal testimony of friends who had suffered from depression and who have been and are being successfully treated by medication. It’s worth underlining that all of them were wonderfully committed Christians.

Jean Francois Millet's "Noonday Rest"

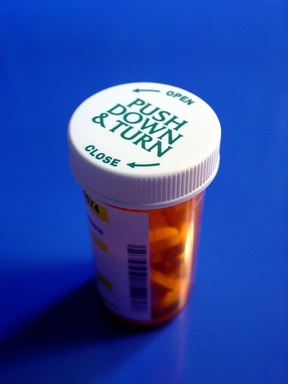

Having many friends in medicine, I went to them and was tested for everything they could imagine (seems like they drew gallons of blood!). All the tests came back negative. Then my GP suggested maybe I was depressed. I quickly wroteoff that diagnosis by insisting that I was not unhappy. I was just always tired. Nevertheless, he told me that when I was ready to accept that possibility, he would refer me to a psychiatrist. As a former clinician, using medication is in principle not a problem for me. Yet I had reservations about psychiatric drugs; I just didn’t want to be hooked to pills. Besides, I didn’t for a second believe that I was depressed. I was living my professional dream—teaching and researching science and religion in a public university. But in fact, I was depressed, and worst I didn’t know it despite being told that it was probably cause of my tiredness.

So how did I end up in the psychiatrist’s office? It was the personal testimony of friends who had suffered from depression and who have been and are being successfully treated by medication. It’s worth underlining that all of them were wonderfully committed Christians. Looking back now, this is where I believe the Lord started sending messengers (angels) my way. The first was a university professor in the medical school who seemed to be one of the happiest people I knew. This person shared stories of not being able to function without medication. Another was a professor I met at an ASA meeting who revealed to me their family tree was dotted with suicides. A third was a personal friend, one of the most stable individuals I’ve ever met. This is a clinician who was put on meds following graduate school, and who told me it saved her marriage. Lastly, a dental classmate came forward. He was instrumental in my coming to Christ. He was also one of most energetic people I’ve known. His story of depression reducing him to a shadow of a man hit close to home, because when he shared his story, I was working no more than four to five hours a day. It was at that point that I phoned my GP and asked for a referral to a psychiatrist. And I have never regretted that decision. I think it’s worth sharing a bit about my experience with the medications, and of course this is only my experience because people react differently to them. It took eight months and seven different drugs before finding one that worked. Some of these made me incredibly nauseous with pounding headaches. I was within three weeks of handing in my resignation at Christmas 2010 before a drug started to have a positive effect. It was slow and very subtle. The naps in the afternoon got shorter and shorter, and after about a month, they stopped completely. It’s worth noting there is no sense of feeling “high” or “jacked-up.” Surprisingly, and this may seem hard to believe, but I had forgotten what it was to feel rested. That’s the main “feeling” I have experienced being on medication. About eight months into the treatment, I slipped a bit, and my psychiatrist placed me on a second medication. This often happens. My only restrictions are that I have to take the drugs on schedule and be in bed about the same time every night. This past summer I was slowly removed from one of my anti-depressants, and this coming summer, we’ll try stopping the second. But my psychiatrist thinks I will probably be on this one for the rest of my life. So be it. At least, I got my life back. One of the most revelatory moments of my battle with depression was a comment made by my pharmacist when the first drug started to work. I told him that I probably should have been on anti-depressants 10-12 years ago. He replied, “You have no idea how many people say this the first time a medication works.” Then he said, “It’s the stigma of depression within our culture that stops us from seeking treatment.” Roughly 20-25% of us will suffer from depression requiring medication, but regrettably many will suffer without knowing help is near. And this is the reason I wrote this short testimonial. The stigma about depression needs to be destroyed. And those who have benefited from anti-depressants need to stand up and be heard. For me, it was the testimony of Christian friends that was critical in my seeking treatment. I’m quite passionate about this topic. In my Science and Religion class, there is a point in the course where I put my anti-depressants on an overhead and tell the students that I would not be teaching if it were not for the medication. It gets pretty quiet in the classroom. It’s a poignant and holy moment. Thankful emails from students on medication quickly arrive. Most are from Christians who feel “guilty” and “damaged” for being on meds. I assure them that it’s not against God’s will. Rather, we should praise the Lord because we live in a time when the blessing of psychiatric science can help heal our brains and souls. |