God and Nature Winter 2023

By Sy Garte

Astrobiology is an interesting field of science. It is based more on hope and belief than on hard evidence that life exists elsewhere in the universe, and that we might be able to find and study it. There is reason for this belief—mainly, the huge number of planets in our own galaxy, and the statistical likelihood that many (maybe millions) of these planets have the necessary conditions for life (the right size, right position, right composition, etc.).

One of the major goals of astrobiology is to come up with techniques that could allow scientists on earth to be able to detect the presence of life remotely, without needing to actually go to extremely distant planets. A recent paper in Nature (1) reports on a novel and very promising approach to life detection that has the advantage of making no assumptions about the nature of alien life other than it is composed of chemicals. That is, at least to me, a perfectly valid assumption, since most of the alternatives proposed in various science fiction scenarios have too many irreconcilable difficulties to be believed.

Astrobiology is an interesting field of science. It is based more on hope and belief than on hard evidence that life exists elsewhere in the universe, and that we might be able to find and study it. There is reason for this belief—mainly, the huge number of planets in our own galaxy, and the statistical likelihood that many (maybe millions) of these planets have the necessary conditions for life (the right size, right position, right composition, etc.).

One of the major goals of astrobiology is to come up with techniques that could allow scientists on earth to be able to detect the presence of life remotely, without needing to actually go to extremely distant planets. A recent paper in Nature (1) reports on a novel and very promising approach to life detection that has the advantage of making no assumptions about the nature of alien life other than it is composed of chemicals. That is, at least to me, a perfectly valid assumption, since most of the alternatives proposed in various science fiction scenarios have too many irreconcilable difficulties to be believed.

The approach is called Assembly Theory, and it is based on a fairly simple premise, although the details are far from simple. I will not go into those here—they can be found in the Nature paper. My purpose instead is to present the basic idea of the theory in summary, go over some of the results, and discuss the implications for another, equally difficult area of biological science—the origin of life.

Assembly theory hypothesizes that living creatures are capable of synthesizing more complex (and larger) molecules than can be made spontaneously by abiotic (nonliving) chemical and physical processes. The paper (1) presents both a theoretical approach to calculation of a complexity factor called the molecular assembly index (MA), and an experimental method to determine the MA value of any chemical using a form of mass spectroscopy (MS). There is good agreement between the calculated and experimental results. The authors also tested the ability of the MA value of complexity to distinguish chemicals that we know originated from life from those that did not.

FIGURE 1 The abiotic (nonliving) molecules are in pink and the biotic (from life) molecules are in green.

The results are very impressive, and show that a complexity level of MA = 15 is the maximum that can be achieved by abiotic chemical synthesis. In contrast, molecules from life span the entire range of MA values, including far above the MA = 15 limit for nonliving sources,l as shown above in Figure 1 (Figure 4A in the Nature paper). The experiment tested over a million chemicals from many sources. In no case did any non-biological chemical surpass the MA = 15 barrier. This means that an analysis of a planet’s chemical composition could determine the presence of life if any signal greater than MA = 15 were detected using a MS machine.

Assembly theory hypothesizes that living creatures are capable of synthesizing more complex (and larger) molecules than can be made spontaneously by abiotic (nonliving) chemical and physical processes. The paper (1) presents both a theoretical approach to calculation of a complexity factor called the molecular assembly index (MA), and an experimental method to determine the MA value of any chemical using a form of mass spectroscopy (MS). There is good agreement between the calculated and experimental results. The authors also tested the ability of the MA value of complexity to distinguish chemicals that we know originated from life from those that did not.

FIGURE 1 The abiotic (nonliving) molecules are in pink and the biotic (from life) molecules are in green.

The results are very impressive, and show that a complexity level of MA = 15 is the maximum that can be achieved by abiotic chemical synthesis. In contrast, molecules from life span the entire range of MA values, including far above the MA = 15 limit for nonliving sources,l as shown above in Figure 1 (Figure 4A in the Nature paper). The experiment tested over a million chemicals from many sources. In no case did any non-biological chemical surpass the MA = 15 barrier. This means that an analysis of a planet’s chemical composition could determine the presence of life if any signal greater than MA = 15 were detected using a MS machine.

The details of calculation of the MA index are complicated. In short, the basic algorithm involves counting bonds between atoms and adding them. But repetitive chemical elements are accounted for separately, so the total value of the MA is dependent on how many and what size various repetitive elements exist in a molecule. Details and examples can be found in the Supplementary Material (2).

So what kind of chemicals can be formed outside of life, and what are the kinds that cannot? All of the amino acids have MA scores less than 15, consistent with experimental demonstrations that amino acids can be formed outside of life. The same may be said for most dipeptides, compounds composed of two amino acids linked together. But when we look at tripeptides, things get messier. A set of three different amino acids linked together is more likely to have an MA score above 15 than below it. And with larger peptides (four or more amino acids), the score is almost always above 15. This point is not thoroughly explored in the paper, but it is consistent with the data in Figure 2 (Figure 4C in the Nature paper) showing the results for two dipeptides and for a mixture of “urinary peptides” that are not further characterized but presumably represent a wide range of peptide sizes and compositions.

FIGURE 2 The first two columns show dipeptides, and third is a mix of peptides from urine.

That’s a problem for the assumption of a purely chemical abiogenesis. The most commonly held current view in origin-of-life research is that an RNA-peptide world (rather than just RNA world) came before modern DNA-based life. But such a scenario envisages abiotic synthesis of peptides composed of at least 5-8 amino acids. The assumption that peptides with that degree of complexity could be easily produced from amino acids is questioned by these results on a complexity limit on abiotic molecules.

So what kind of chemicals can be formed outside of life, and what are the kinds that cannot? All of the amino acids have MA scores less than 15, consistent with experimental demonstrations that amino acids can be formed outside of life. The same may be said for most dipeptides, compounds composed of two amino acids linked together. But when we look at tripeptides, things get messier. A set of three different amino acids linked together is more likely to have an MA score above 15 than below it. And with larger peptides (four or more amino acids), the score is almost always above 15. This point is not thoroughly explored in the paper, but it is consistent with the data in Figure 2 (Figure 4C in the Nature paper) showing the results for two dipeptides and for a mixture of “urinary peptides” that are not further characterized but presumably represent a wide range of peptide sizes and compositions.

FIGURE 2 The first two columns show dipeptides, and third is a mix of peptides from urine.

That’s a problem for the assumption of a purely chemical abiogenesis. The most commonly held current view in origin-of-life research is that an RNA-peptide world (rather than just RNA world) came before modern DNA-based life. But such a scenario envisages abiotic synthesis of peptides composed of at least 5-8 amino acids. The assumption that peptides with that degree of complexity could be easily produced from amino acids is questioned by these results on a complexity limit on abiotic molecules.

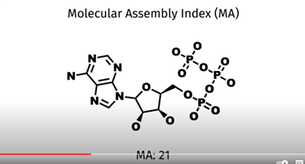

But things are much worse for the RNA side of the hypothesis. It turns out that the MA score for adenosine triphosphate (ATP, one of the four building blocks of polynucleotides, the precursors of RNA long polymers) is 21 (see Figure 3 from the linked video (3)), far above the abiotic limit. And, of course, this implies that even dinucleotides, let alone small stretches of RNA, could not occur outside of life, at least not in significant quantities.

FIGURE 3 The structure of ATP, a basic building block of RNA and DNA, with MA = 21

I want to thank YouTuber John Maddox for alerting me to this paper and sparking my interest in what these results could mean for abiogenesis based on purely chemical processes. While the authors’ focus in this work is the detection of life on exoplanets, not the origin of life, I believe the implications of a cutoff of complexity beyond a particular threshold for abiotic chemical synthesis are profound, perhaps even revolutionary.

I should add that the senior author of this paper is certainly not someone who doubts the reality of naturalistic abiogenesis based solely on random interactions of chemicals, nor is he a skeptic about early precursors to polymer construction before life began. It is British chemist Lee Cronin, a man who has engaged in lively (to use a polite term) debate with abiogenesis skeptic James Tour, a synthetic organic chemist and a Christian.

I saw no comment from Cronin or any of the other authors of the paper, either in follow up papers or in a video describing the work (3), mentioning what to me look like dramatic implications of this research for the origin-of-life paradigms currently being explored in many labs.

One possible reason for this silence may be that I am misinterpreting the findings of the paper, and there are in fact no such negative implications. Perhaps the results have no bearing on the likelihood of a purely chemical origin of life. For example, it could be that the upper limit of 15 for chemical complexity from abiotic synthesis is not completely rigid, and that rare examples of decapeptides and 20-50-member polynucleotide chains (without branching due to 5’ to 2’ bonding) can be constructed outside of life. The authors in fact emphasize that their interest is not in the absolute probability of a specific molecule ever forming—rather, it is the complex molecules’ presence in abundant quantities that an astrobiologist would look for as a marker for life. Perhaps a few extremely rare abiotically formed molecules can find a way to avoid hydrolysis, become stable by interacting with each other, and then… I don’t know, maybe some process could lead to further synthesis and concentration of such molecules.

I would welcome any comments or suggestions from readers on this subject, as I am only a biochemist who is very likely missing something here. I promise that all such commentary will be promptly published in the magazine (I have a special relationship with the Editor-in-Chief) for the further enlightenment of our readers.

References

1. Marshall, S.M., Mathis, C., Carrick, E. et al. Identifying molecules as biosignatures with assembly theory and mass spectrometry. Nat Commun 12, 3033 (2021).

2. https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41467-021-23258-x/MediaObjects/41467_2021_23258_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

3. Universal Life Detection: Astrobiology & Assembly Theory

NASA Astrobiology 9/2/2021 Link

Sy Garte, Ph.D. Biochemistry, is Editor-in-Chief of God and Nature, and the author of The Works of His Hands: A Scientist's Journey from Atheism to Faith. He is currently Visiting Professor at Rutgers University and has been a Professor of Public Health and Environmental Health Sciences at three universities. He was an Associate Director at the Center for Scientific Review at the NIH. He blogs at The Book of Works, and his website is sygarte.com. Sy is Vice President of the Washington DC ASA Chapter, and a fellow of the ASA.

FIGURE 3 The structure of ATP, a basic building block of RNA and DNA, with MA = 21

I want to thank YouTuber John Maddox for alerting me to this paper and sparking my interest in what these results could mean for abiogenesis based on purely chemical processes. While the authors’ focus in this work is the detection of life on exoplanets, not the origin of life, I believe the implications of a cutoff of complexity beyond a particular threshold for abiotic chemical synthesis are profound, perhaps even revolutionary.

I should add that the senior author of this paper is certainly not someone who doubts the reality of naturalistic abiogenesis based solely on random interactions of chemicals, nor is he a skeptic about early precursors to polymer construction before life began. It is British chemist Lee Cronin, a man who has engaged in lively (to use a polite term) debate with abiogenesis skeptic James Tour, a synthetic organic chemist and a Christian.

I saw no comment from Cronin or any of the other authors of the paper, either in follow up papers or in a video describing the work (3), mentioning what to me look like dramatic implications of this research for the origin-of-life paradigms currently being explored in many labs.

One possible reason for this silence may be that I am misinterpreting the findings of the paper, and there are in fact no such negative implications. Perhaps the results have no bearing on the likelihood of a purely chemical origin of life. For example, it could be that the upper limit of 15 for chemical complexity from abiotic synthesis is not completely rigid, and that rare examples of decapeptides and 20-50-member polynucleotide chains (without branching due to 5’ to 2’ bonding) can be constructed outside of life. The authors in fact emphasize that their interest is not in the absolute probability of a specific molecule ever forming—rather, it is the complex molecules’ presence in abundant quantities that an astrobiologist would look for as a marker for life. Perhaps a few extremely rare abiotically formed molecules can find a way to avoid hydrolysis, become stable by interacting with each other, and then… I don’t know, maybe some process could lead to further synthesis and concentration of such molecules.

I would welcome any comments or suggestions from readers on this subject, as I am only a biochemist who is very likely missing something here. I promise that all such commentary will be promptly published in the magazine (I have a special relationship with the Editor-in-Chief) for the further enlightenment of our readers.

References

1. Marshall, S.M., Mathis, C., Carrick, E. et al. Identifying molecules as biosignatures with assembly theory and mass spectrometry. Nat Commun 12, 3033 (2021).

2. https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41467-021-23258-x/MediaObjects/41467_2021_23258_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

3. Universal Life Detection: Astrobiology & Assembly Theory

NASA Astrobiology 9/2/2021 Link

Sy Garte, Ph.D. Biochemistry, is Editor-in-Chief of God and Nature, and the author of The Works of His Hands: A Scientist's Journey from Atheism to Faith. He is currently Visiting Professor at Rutgers University and has been a Professor of Public Health and Environmental Health Sciences at three universities. He was an Associate Director at the Center for Scientific Review at the NIH. He blogs at The Book of Works, and his website is sygarte.com. Sy is Vice President of the Washington DC ASA Chapter, and a fellow of the ASA.