I Really Did That Work: A brief survey of notable Christian women in science

by Lynn Billman

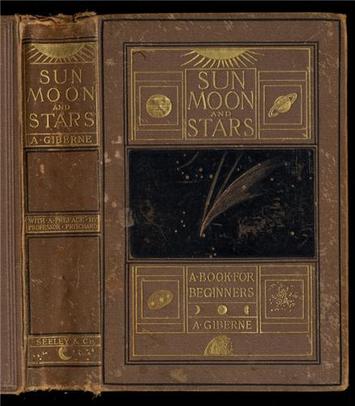

Everyone, it seems, has heard of Madame Maria Curie – the woman scientist who developed the first theories of radioactivity, invented the term radioactivity, started major centers of medical research in Paris and Warsaw, discovered radium and polonium, invented mobile X-ray units for use on World War I battlefields, and the only person to ever receive two Nobel prizes in different fields (physics and chemistry). While her amazing achievements will always merit a full sidebar in many science textbooks, many other female scientists of the recent past are now being recognized for their achievements also. Of these many women, some were also Christians.[1] This article will share with you the inspiring stories of five Christian women scientists of the past 100 years, from different fields and different denominations. Discoverer of the Plesiosaur As a young child in England, Mary Anning (1799-1846) was fascinated by the strange rocks in the fossil-rich region of Lyme Regis in Dorset near the sea. Fossil collecting was a popular hobby in the late 18th and early 19th century, but gradually developed into a science as the importance of fossils became better understood. Anning searched for fossils in the area's Blue Lias cliffs, particularly during the winter months when landslides exposed new fossils that had to be collected quickly before they were lost to the sea. It was dangerous work, and she nearly lost her life in 1833 during a landslide. Google Inc paid homage to the 215 anniversary of the birth of Mary Anning on May 21 2014 with this Doodle on the homepage. (See header, above.) For thirty years, Anning collected, prepared, and described many marine fossils of the Jurassic age, before anyone really grasped the idea of the passage of millions of years of time on the earth. She found the first two plesiosaur skeletons ever found, the first ichthyosaur to be recognized, and the first pterosaur outside of Germany. Her work strongly influenced William Buckland and Georges Cuvier, scientists who are credited with the describing the first true dinosaur and conceptualizing the “age of reptiles.” While her social class and gender limited her acceptance in the scientific community of Britain at the time, Anning's work drew considerable attention in England. Her descriptions and ideas contributed to fundamental changes in scientific thinking about prehistoric life and the history of the Earth, despite diverging from the Biblical understanding of creation at that time. In 2010, the Royal Society included Anning in a list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science. Astronomer Who Inspired All Ages to Understand Astronomy The quest for knowledge during Victorian England of the 19th century inspired both men and women – but too much knowledge in a woman was considered unfeminine. Male writers dominated the expanding market for books about science. Yet, Agnes Giberne (1845-1939) was undaunted. She loved science, especially astronomy. Giberne realized that there was a particular need for instructive books on astronomy which provided an introduction to the science. Her inspiring language created wonder in her readers while teaching about the development of the universe, the distances of the stars and planets, and comets and eclipses. Her use of analogies and dialogue helped engage readers in the theme of the cosmic journey and she urged her readers to learn about the sun, moon, and planets “on the wings of imagination.” Reviewers celebrated her astronomical works; the scientific journal Nature reviewed all the astronomy books she published from 1893 to 1921. In Sun, Moon, and Stars: Astronomy for Beginners (1879) she uses the metaphor of a family to describe the solar system. In 1895 she published a sequel, Radiant Suns, which explained the theories of the motion of the heavens from ancient Middle Eastern ideas to contemporary theories of spectral analysis. Featuring a foreword by Oxford Professor of Astronomy Charles Pritchard, this work was printed in several editions on both sides of the Atlantic. It sold 24,000 copies before the end of the century. As a devout Anglican, Giberne often called attention in her writing to the religious significance of the heavens as the home of God and how awe-inspiring the heavens are. She also wrote for the Religious Tract Society, creating fictional stories with Christian themes. A prayer in Through the Linn; or, Miss Temple’s Wards (1881), was quoted in over 100 books of the early 20th century. It reads, in part, “Gracious Savior, gentle Shepherd, Children all are dear to Thee; Gathered with Thine arms and carried in Thy bosom may we be.” Growing interest in astronomy led to the formation of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1820. But women astronomers had extremely limited opportunities to participate in this prestigious society. Late in the 1800s, amateur astronomers began to reject both the high fees charged by the Royal Astronomical Society and its treatment of women, and in 1890 formed the British Astronomical Association where women were welcomed in full participation. Giberne, along with Agnes Mary Clerke (see below) and three other women, served on the first 48-member governing council of the British Astronomical Association. Astronomer Who Popularized Astrophysics and Astronomy A contemporary of Agnes Giberne, Agnes Mary Clerke (1842-1907) was born in Ireland and lived also in Italy and England. Studying the stars since she was less than 15 years old, she also studied writing and literature in Italy. After returning to England, she published her first important article, “Copernicus in Italy,” in the “Edinburgh Review” in 1877. Her exhaustive and authoritative work, “A Popular History of Astronomy in the Nineteenth Century,” established her worldwide reputation as an author in 1885. Clerke’s special focus was astrophysics, astronomers, and astronomy, including spectroscopy. She diligently gathered facts and knowledge, discussed what she learned with others, and suggested problems and lines of research to pursue. In all, she wrote six books and published more than 60 articles on these subjects, published in such prestigious reviews and periodicals as the “Edinburgh Review,” “Encyclopaedia Britannica,” and the “Catholic Encyclopedia.” Along with three other women, Clerke was one of the first four women among the inaugural members of the British Astronomical Association. She was also elected an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1903, an honor only awarded to a handful of other women. Clerke, a Roman Catholic, was a woman of deep spiritual conviction. With her scientific skills, she combined “a noble religious nature that made her acknowledge with supreme conviction the insufficiency of science to know and predict the possible acts of Divine Power.” Discoverer of the Ring Structure of Benzene The tenth child of the town postmaster in a small town in Ireland, Kathleen Lonsdale (1903-1971) had to transfer to a boys’ school because she wanted to study math and physics. In her inspiring life, she went on to do what many women aspire to – make foundational contributions to scientific research, raise a family of three children, and impact the world for peace. She also was named one of the ten most influential women in science in Great Britain in 2010. Lonsdale earned her Bachelors of Science in London at age 19 in 1922, and her Masters in physics in 1924. Because of her impressive work she was invited to join the research team of William Bragg, the 1915 Nobel Laureate in Physics using X-ray technology to study organic compound crystal structures. Lonsdale had a profound influence on the development of X-ray crystallography, a technique used to study the structure of complex molecules in crystal form. Her most famous achievement was experimentally determining the ring structure of benzene, proving that benzene is planar and hexagonal with equal bonds between all six carbon atoms, a foundational contribution to organic chemistry, proving Kekule’s theory of 1865. Among many other successes, she developed divergent-beam X-ray photography of crystals and used this to measure the carbon-to-carbon distance in individual diamonds. Her studies of diamond structure and synthesis was so important that a rare diamond found in meteorites was named lonsdaleite. Lonsdale was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of London in 1945, along with Marjory Stephenson, a biochemist; these were the first women Fellows since the Society was founded in 1660. She was the first female tenured professor at the University College, London, and the first female president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Lonsdale married in 1927 and raised three children. She interrupted her career for a few years to care for her small children, but did continue to work part-time. She returned to the laboratory in 1935, and earned her doctorate in 1936. She wrote, “Sir Lawrence Bragg once described the life of a university professor as similar to that of a queen bee, nurtured, tended and cared for because she has only one function in life. Nothing could be farther from the life lived by the average professional woman.” One of her students went on to become a Professor of Crystallography in Egypt, a woman who credited Lonsdale with demonstrating to her how a woman can balance a career and a family. Lonsdale was brought up in the Baptist denomination, but in 1935 became a Quaker, along with her husband. Both were committed pacifists in that turbulent time. During World War II, she spent a month in prison for refusing to register with the government for civil defense duties. At the annual meeting of British Quakers in 1953, she delivered the keynote address on Removing the Causes of War. Lonsdale was also known widely for her humility and her help to other scientists, for encouraging young people to pursue science, and for encouraging women in science. She wrote once that, just as the British government had regulations ensuring that men returning military service would have a job, a country that wants married women to return to a scientific career after starting a family “should make special arrangements to encourage her to do so.” (If you want to know more about Kathleen Lonsdale, don’t forget to read “Crystallographer, Quaker, Pacifist, & Trailblazing Woman of Science: Kathleen Lonsdale’s Christian Life ‘Lived Experimentally,’” also in this issue of God & Nature!) Sister Celine and Her Prescient Polynomials Mary Fasenmyer (1906-1996) became enamored with mathematics in high school. Growing up in Erie, Pennsylvania’s oil country, she was raised in a devout Roman Catholic family and attended primarily Catholic schools. After high school, she taught and attended classes at Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pennsylvania for ten years. In 1933 she earned her Bachelors degree and also joined the Religious Sisters of Mercy, who ran Mercyhurst College. She became Sister Celine in this non-cloistered religious order, which was founded to help the poor through teaching and medical care. She then taught at a high school in Pittsburgh, but recognizing her talents, her order soon sent her to the University of Pittsburgh for graduate studies. She earned a masters in mathematics with a minor in physics in1937 and returned to earn her doctorate in 1946. Her doctoral work was on combinatorial problems related to hypergeometric series. In simple terms, hypergeometric approaches utilize differential equations on very complex mathematical problems with many factors influencing each other and then boils down all those factors into a single function with relevant inputs so they can be solved. These types of mathematical problems arise frequently in physics, chemistry, biology, social sciences, and economics. In her thesis she developed an algorithm to find recurrence relations between sums of terms in hypergeometric series. Sister Celine published just two papers about her work, on generalized hypergeometric series in 1947 and on recurrence relations in 1949. She then devoted the rest of her life to teaching at Mercyhurst and did no further research. It is doubtful that she recognized the profound importance of her work until much later in life. Her work was mentioned in a 1960 book by her research adviser, Earl Rainville, but it was not until 1978 that the potential and importance of her work was truly recognized. At that time, Doron Zeilberger, a mathematician at Rutgers, realized the power of Sister Celine’s ideas. Zeilberger and Herbert Wilf, Professor of Mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania, pushed Sister Celine’s ideas further into what has become the well-known “WZ Theory.” By this time, computers were in common use in universities, and Sister Celine’s approach was ideally suited for use with computers. As another mathematician, Donald Knuth, said, “No longer do we need to get a brilliant insight in order to evaluate sums of binomial coefficients, and many similar formulas that arise frequently in practice; we can now follow a mechanical procedure and discover the answers quite systematically.” Today, the hypergeometric series that she solved are called “Sister Celine’s polynomials.” Finally, in 1994, Sister Celine got her recognition. Herbert Wilf went to the retirement home in Erie where she lived and invited her to attend a mathematics conference in Florida. The diocese awarded her a travel grant. As Wilf reported: When I introduced her from the audience, the 87-year-old nun slowly rose to her feet. She said she had only two remarks to make. First, she wanted to thank Professor Wilf for the invitation. And second, she said, casting a level gaze at the assemblage of distinguished mathematicians, "I want you all to know - I really did that work." There wasn't a dry eye in the house. [1] Madame Curie was apparently not a Christian, as an adult. According to a study by Robert Reid (Wikipedia ref 13), Madame Curie’s father was an atheist and her mother a devout Catholic. But her mother died of tuberculosis when Maria was only ten years old, and her oldest sister had died of typhus three years earlier. These deaths, it is reported, caused her to give up Catholicism. |