Science Falsely So Called: Fundamentalism and Science

Figure 1: Cartoon by Ernest James Pace, courtesy of the Billy Graham Center

by Edward B. Davis

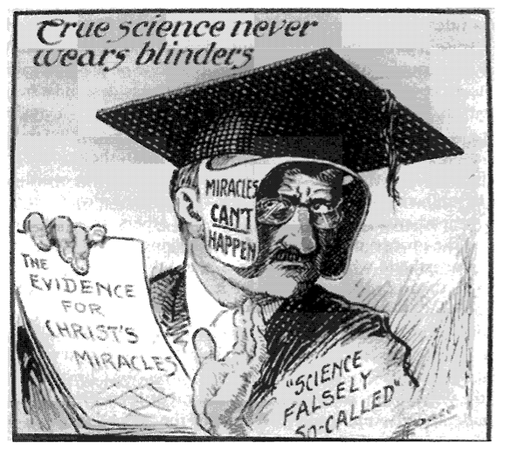

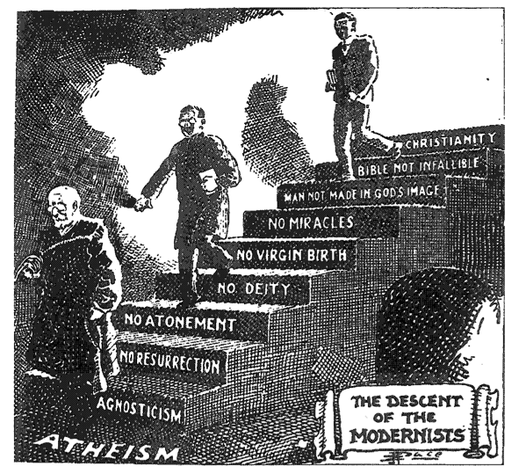

(This essay by ASA member Ted Davis was first published as a chapter in the Blackwell Companion to Science and Christianity) The trial of John Scopes for teaching evolution in a Dayton, Tennessee, high school in 1925 is undoubtedly the most famous episode in the history of fundamentalism and science. Although it was technically a criminal prosecution, everyone in the courtroom wanted and expected a conviction—including the defendant, an inexperienced teacher who was unsure that he had actually taught evolution but had agreed to stand trial at the insistence of his employers. The ultimate goal was to test the constitutionality of a new law that prohibited public school teachers “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man had descended from a lower order of animal” (Larson 1997, 50). The proceedings were carefully orchestrated, resulting in an almost theatrical trial. In the penultimate scene, the noted agnostic Clarence Darrow, the greatest trial lawyer of his generation, aggressively cross-examined William Jennings Bryan, who had run three times unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for President decades earlier and who had spearheaded the effort to pass laws against evolution in many states. The topic of that inquisition was the Bible. For some time, Bryan had been writing regular columns about biblical stories for newspapers, and he regarded himself as something of an authority on the holy book. Bryan had gone to Dayton at the behest of William Bell Riley, pastor of the enormous First Baptist Church of Minneapolis and a bitter opponent of evolution. Riley was the founding president of the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association, a confederation of conservative Protestants who vigorously opposed what they considered to be the profoundly unbiblical views of those liberal Protestants who were calling themselves “modernists.” Shortly before World War One, California oil magnates Lyman and Milton Stewart had financed a trans-Atlantic collection of ninety articles in twelve paperbound volumes, The Fundamentals (1910-1915), which were printed by the millions and mailed free of charge to Protestant pastors, Sunday school superintendents, and other religious workers across the nation. It was in reference to the title of this collection that the word “fundamentalist” was first used in print in July 1920 by Curtis Lee Laws, editor of a leading Baptist periodical, the Watchman-Examiner. Laws suggested “that those who still cling to the great fundamentals and who mean to do battle royal for the fundamentals shall be called ‘Fundamentalists’,” adding that “when he uses the word it will be in compliment and not in disparagement” (Moore 1981, 32). Although now the term is applied far more broadly and usually with a decidedly uncomplimentary intent, the specifically Protestant and American context in which it arose must be kept in mind. Surprisingly, evolution had not been a principal target of The Fundamentals; the authors as a group were far more concerned about heterodox theology and the “German fancies” of higher biblical criticism. Only two of the articles can be described as mainly antievolutionary, and a few contributors actually favored theistic evolution—especially the Scottish theologian James Orr, who wrote that “‘Evolution,’ in short, is coming to be recognized as but a new name for ‘creation,’ only that the creative power now works from within, instead of, as in the old conception, in an external, plastic fashion” (Numbers 2006, 49). James Moore (1979) and David Livingstone (1984) have shown that some important evangelicals substantially accepted evolution among the lower animals (though always with an obvious element of divine design) for several decades prior to World War One: Harvard botanist Asa Gray (the first Darwinian in America), geologists George Frederick Wright (who later changed his mind and wrote against evolution in The Fundamentals) and James Dwight Dana, theologians James McCosh and Augustus Hopkins Strong, and even an author of the Princeton doctrine of inerrancy, theologian Benjamin B. Warfield. Human evolution, especially the evolution of our higher faculties, remained highly problematic for most of these thinkers—and the one exception, Gray, probably did not accept it until the final decade of his life—but none believed that evolution among the lower animals contradicted core Christian doctrines such as creation, Incarnation, and Resurrection. Nevertheless, as George Marsden (1988, n.p.) has pointed out, most of the articles in The Fundamentals share the view “that true science and rationality supports traditional Christianity grounded in the supernatural and the miraculous,” such that subsequent heated opposition to evolution is not too hard to understand. The concerns fundamentalists expressed about scientific naturalism, relative to the Bible, were captured brilliantly in a cartoon (Figure 1) drawn by Ernest James Pace for the Sunday School Times, a weekly magazine with a large circulation in the United States and more than one hundred other nations. Pace’s cartoons appeared regularly in the Sunday School Times and other periodicals for almost thirty years, spreading fundamentalist views of science and the Bible pictorially to a very wide audience. Bryan had personally opposed evolution for many years, but he did not seek publicly to ban its teaching until the early 1920s. He was motivated to act by what he read about links between Darwinian ideas and militarism in Germany prior to and during World War One, particularly in a book by Stanford biologist Vernon Kellogg called Headquarters Nights (1917). Kellogg, a pacifist who had earned his doctorate at Leipzig, volunteered to help Herbert Hoover with relief efforts in Belgium before the United States declared war on Germany. Billeted in a house that was also shared by German officers, he wrote about their conversations. Reflecting on his experiences, Kellogg said that “The creed of the Allmacht of a natural selection based on violent and fatal competitive struggle is the gospel of the German intellectuals,” on which basis they justified “why, for the good of the world, there should be this war” (Kellogg 1917, 28 and 22). These revelations shocked Bryan, who was already convinced that belief in evolution justified monopolistic practices, enhanced class pride, and undermined the moral basis for democracy in America.  Figure 2: "The descent of the Modernists" by Pace. Courtesy of Edward B Davis Figure 2: "The descent of the Modernists" by Pace. Courtesy of Edward B Davis

Evolution as False Science and Bad Theology

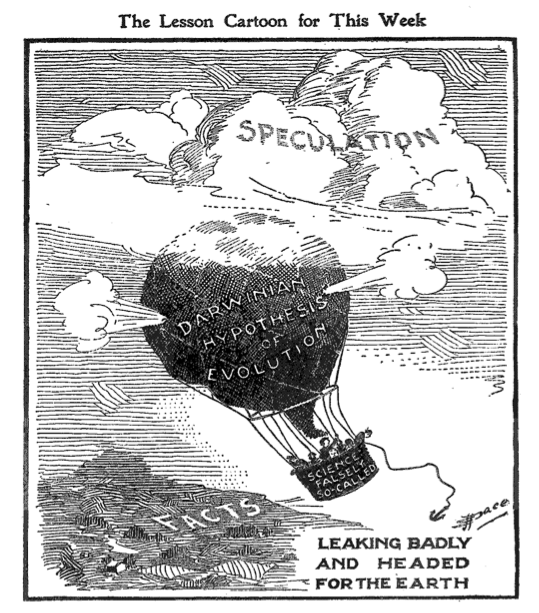

Both Bryan and Riley blamed Germany for cradling biblical criticism and Darwinian philosophy, and they both saw evolution as underlying the false theology of the modernists. It can be no accident that the antievolutionary screed written by Bryan in 1922, The Menace of Darwinism, bore a title highly similar to a book by Riley from five years earlier, The Menace of Modernism. As Bryan told Charles G. Trumbull, the editor of the Sunday School Times, evolution was “the cause of modernism and the progressive elimination of the vital truths of the Bible.” The Christian who accepted evolution would almost inevitably descend a staircase of increasing unbelief, on which “there is no stopping place” short of atheism—a vivid image that Pace converted into one of his most powerful cartoons (Figure 2). According to Bryan, “the three persons who are most affected by modernism are the student, the preacher who substitutes education for religion, and the scientist who prefers guesses to the word of God” (Moore 1981, 40). Thus, Bryan had a special revulsion for “theistic evolution,” a term that had been used (not always sympathetically) by Dawson, Gray, and others since the 1870s to denote the idea that God used the process of evolution to create living things. “Theistic evolution may be described as an anesthetic which deadens the pain while the patient’s religion is being gradually removed,” Bryan proclaimed, making it just “a way-station on the highway that leads from Christian faith to No-God-Land” (Bryan 1922, 5). Bryan’s fears about the deleterious effects of evolution on traditional Christian beliefs were not unwarranted. Most Protestant scientists and clergy who accepted evolution at that time coupled their high view of science with a low view of orthodox Christian theology, rejecting the Incarnation, the virgin birth, the bodily Resurrection of Jesus, and even in some cases the idea of a transcendent God. American Protestants of the Scopes era were presented with a stark choice: to affirm traditional Christian beliefs while denying evolution, or to accept evolution while discarding orthodox beliefs. Thus, when Scopes’ attorneys invited more than a dozen eminent scientists and theologians to testify on behalf of evolution at the trial (many of them declined), most were modernist Christians and possibly just one really believed in the Incarnation—the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Columbia physicist Michael Pupin, a devout Serbian Orthodox believer whose religious tradition was not involved with the fundamentalist-modernist controversy. The list included theologian Shailer Mathews, dean of the Divinity School at the University of Chicago, the most influential seminary in America. When Mathews penned his autobiography in the mid-1930s, he spoke of how the addition of laboratory science into the educational process resulted in the attitude “that orthodox theology was felt to be incompatible with intellectual integrity” (Mathews 1936, 221). Another invitee, Princeton biologist Edwin Grant Conklin, almost took the words out of Bryan’s mouth, describing his own spiritual journey as one that “orthodox friends” might interpret as “descending steps,” leading him further from the traditional Methodist faith of his youth. “[M]y gradual loss of faith in many orthodox beliefs,” he recalled, “came inevitably with increasing knowledge of nature and growth of a critical sense” (Conklin 1953, 57-58). In arguing against evolution, Bryan, Riley, and other fundamentalists typically distinguished “true science” of solidly proven “facts” from “false science” of speculative “theories” such as evolution. “The word hypothesis is a synonym used by scientists for the word guess,” as Bryan liked to say. “If Darwin had described his doctrine as a guess instead of calling it an hypothesis, it would not have lived a year.” (Bryan 1922, 21) In his closing statement from the Scopes trial (which the judge did not actually allow him to deliver in the courtoom), Bryan took this attitude even further: “Evolution is not truth, it is merely an hypothesis—it is millions of guesses strung together” (Larson 1997, 7). Following Bryan’s death a few days after the Scopes trial, his role was filled by Harry Rimmer, a self-educated itinerant evangelist who became the most influential antievolutionist of the period between the world wars. In 1921, Rimmer had formed a one-man think tank called the Research Science Bureau, to prove that science was compatible with biblical literalism and to advance “the harmony of true Science and the Word of God” (Numbers 2006, 78). Four years later, in the first of his more than two dozen pamphlets about science, Rimmer distinguished “between true science, (which is knowledge gained and verified) and ‘modern’ science, which is so largely speculation and theory” (Davis 1995, 462). Commonsense realism of this sort, ultimately derived from Francis Bacon or Thomas Reid, was deeply embedded in nineteenth-century American thought (Marsden 1983). Even in the early twentieth century, the fundamentalists were hardly outliers in this respect, and they pushed the point at every opportunity. Another cartoon by Pace delivered this message quite effectively (Figure 3). As Pace’s images (Figures 1 and 3) also show, the fundamentalists often labeled evolution “science falsely so called,” a reference to 1 Timothy 6:20 (Numbers & Thurs 2011). The same terminology had been used for centuries by numerous Christian authors in reference to diverse philosophical views, including Gnosticism, but since the early nineteenth century it has especially been applied to modern natural history. Samuel Miller, a Presbyterian minister from New York and a member of the American Philosophical Society, set the tone for many American Christians in 1803, when he described the previous century as “the age of infidel philosophy.” One finds “in every age ‘profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of science falsely so called.’” Never before have there been “so many deliberate and systematic attacks … on Revealed Religion, through the medium of pretended science,” which was “pushed to an atheistical length by some who assumed the name, and gloried in the character of philosophers.” Miller was especially concerned about natural history, which “has been pursued with unwearied diligence, to find evidence which should militate against the information conveyed in the Scriptures.” By contrast, “every sober and well-directed inquiry into the natural history of man, and of the globe we inhabit, has been found to corroborate the Mosaic account of the Creation, the Fall, the Deluge, the Dispersion, and other important events recorded in the sacred volume” (Miller 1803, 431 and 434). In short, false science contradicted a literal interpretation of Genesis while true science did not. The Anglican rector George Bugg expressed this perfectly in the title of a book that was published anonymously in 1826-27, Scriptural Geology; or, Geological Phenomena Consistent Only with the Literal Interpretation of the Sacred Scriptures, Upon the Subjects of the Creation and Deluge. Thus, for Bugg, the conclusion that the sun and stars “existed thousands of ages before the Mosaic creation” was nothing other than “philosophy [i.e., science] ‘falsely so called’.” Genuine philosophers, on the other hand, “know nothing about creation but what the Scriptures tell them” (1826-27, I, 136, italics in the original). Strict literalism of this sort, in which a long pre-human natural history is flatly rejected on biblical grounds, mostly disappeared in America before the Civil War, surviving mainly among the Seventh-day Adventists and a few other groups on the fringes of Protestantism, only to be revived a century later with the rapid rise of scientific creationism. Fundamentalists and the Age of the Earth The fundamentalists of the 1920s fully accepted the geological ages, to such an extent that Riley could not identify a single “intelligent fundamentalist who claims that the earth was made six thousand years ago; and the Bible never taught any such thing” (Numbers 2006, 60). Geology and the Bible were usually reconciled in one of two ways. Bryan, Riley, and many others adopted the approach described as “progressive creation” by Benjamin Silliman (1829, 121), the first professor of natural history at Yale and the single most influential science educator in antebellum America. Silliman had pointed out that the fossil record harmonized pretty well with the order of events in Genesis, provided that one interpreted the six “days” of creation figuratively as references to the geological ages, culminating in the separate creation of humans on the final “day.” Silliman’s eminent successor at Yale, Dana, taught a similar position in the 1850s and continued to maintain a semi-creationist position on human origins even in the final edition (1894) of his Manual of Geology, the definitive text at the time. Dana’s contemporaries Arnold Guyot, a Swiss-born glacial geologist who taught at Princeton, and John William Dawson, the leading Canadian geologist of his generation and a great admirer of Dana and Guyot, both made their scientific reputations while holding progressive creationist views. Both also influenced the fundamentalists long after their deaths—especially Dawson, whose many writings on biblical topics led him to be regarded as a champion for the scientific credibility of the Bible; his name was invoked at least ten times in The Fundamentals. With regard to evolution, Dawson cautioned readers “to keep speculation in its proper place as distinct from science” and to bring “common-sense to bear on any hypothesis which may be suggested. Speculations as to origins may have some utility if they are held merely as provisional,” but “they become mischievous when they are introduced into text-books and popular discourses, and are thus palmed off on the ignorant and unsuspecting for what they are not.” Anyone who presents the common descent of species to a popular audience “as a proved result of science,” he added, “is leaving the firm ground of nature and taking up a position which exposes him to the suspicion of being a dupe or a charlatan” (Dawson 1890, 54-55). This was music to fundamentalist ears. An alternative approach to Genesis, known as the “gap theory,” posited a long period of indeterminate duration after the original creation of the heavens and the earth “in the beginning,” prior to the six days of creation, in which the fossil-bearing rocks (consisting of mainly extinct animals and plants) had been formed. All of the animals in our world today, however, were separately created in six literal days a few thousand years ago. That view had been endorsed early in the nineteenth century by the great evangelical preacher Thomas Chalmers, the first moderator of the Free Church of Scotland, and then by William Buckland, the first professor of geology at Oxford. Its leading American proponent, Edward Hitchcock of Amherst College, wrote the first textbook by an American geologist—a work that had more than thirty editions between 1840 and 1879 and included a detailed analysis of the relationship between the Bible, geology, and natural theology. English theologian G. H. Pember further popularized the gap theory in Earth’s Earliest Ages (1876), a work that was frequently cited by fundamentalists in the twentieth century and remained in print until the 1980s. By the early twentieth century, neither of these harmonizing schemes was still being endorsed by a scientist of the stature of Hitchcock, Dana, or Dawson, but both were mentioned favorably in the heavily annotated Bible edited by Charles I. Scofield (1909), a staunch dispensationalist. A footnote to the first verse of the Bible seemed to encourage a minimalist creationist approach: “But [only] three creative acts of God are recorded in this chapter: (1) the heavens and the earth, v[erse]. 1; (2) animal life, v. 21; and (3) human life, vs. 26, 27.” These correspond to the three places in the creation story where the Hebrew verb bara (“created”) is used. An identical interpretation had been suggested by Guyot in the late nineteenth century (Livingstone 1984, 78-79). The next sentence in the same note, however, all but endorses the gap theory, which postulated an enormous number of separate creations to produce the modern animals: “The first creative act refers to the dateless past, and gives scope for all the geologic ages.” Further notes and subheadings added within the biblical text make it clear that Scofield preferred the gap theory, yet just as clearly he hedged his bets. A note attached to “the evening and the morning were the first day,” for example, instructs readers that “The use of ‘evening’ and ‘morning’ may be held to limit ‘day’ to the solar day; but the frequent parabolic use of natural phenomena may warrant the conclusion that each creative ‘day’ was a period of time marked off by a beginning and ending.” Prior to the 1960s, fundamentalists generally reflected the ambivalence evidenced here: either view was acceptable, but the gap theory, with its literal creation “days,” recent separate creation of humans, and complete rejection of biological evolution, was more popular than any other interpretation—despite the fact that Dawson had decisively rejected it on both scientific and biblical grounds. Scofield himself founded the Philadelphia School of the Bible (now Philadelphia Biblical University), and his Bible was also adopted at Moody Bible Institute (Chicago), the Bible Institute of Los Angeles (now Biola University), and several other Bible schools, soon becoming the most widely used version among fundamentalists and Pentecostals. The first academic dean of BIOLA and the last editor of The Fundamentals, the evangelist and bibical scholar Reuben A. Torrey, took Dana’s course at Yale and embraced his overall attitude of harmonizing nature and scripture, but he adopted the gap theory as the best means to do so—and, like many other proponents of that view, he endorsed the old idea of pre-Adamite humans in order to accommodate fossil hominids to Genesis. However, like Scofield, he tried to have it both ways, combining elements of both views in in his famous book, Difficulties of the Bible (1907). Rimmer, who revered his Scofield Bible, enthusiastically defended the gap view in his many publications and in a famous debate with Riley (who upheld the day-age view) from the late 1920s. Yet he, too, sometimes combined both views in flatly inconsistent ways. Despite the incoherence of their positions, Scofield, Torrey, and Rimmer were very persuasive, such that Baptist theologian Bernard Ramm observed with considerable frustration at mid-century, “the gap theory has become the standard interpretation throughout Fundamentalism, appearing in an endless stream of books, booklets, Bible studies, and periodical articles. In fact, it has become so sacrosanct with some that to question it is equivalent to tampering with Sacred Scripture or to manifest modernistic leanings” (1954, 197).  Figure 3: "Leaking Badly and Headed for Earth" by Pace, courtesy of Princeton Theological Seminary Figure 3: "Leaking Badly and Headed for Earth" by Pace, courtesy of Princeton Theological Seminary

Fundamentalists, Progressive Creation, and the Rise of Young-Earth Creationism

The book in which Ramm made this point, The Christian View of Science and Scripture (1954), was based on lectures he had given shortly after the war at BIOLA, where the gap view still dominated; it is worth noting that he wrote his book right after leaving BIOLA for Bethel College and Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota. For many years BIOLA had offered a required course on “Bible and Science” based heavily on Rimmer’s ideas; Rimmer had actually taught the course at least once himself, and one of his books was still being used as a text. Ramm was assigned to teach it while he was doing graduate study in the philosophy of science at the University of Southern California. Finding himself increasingly dissatisfied with the tone and content of Rimmer’s book (Davis 1995, xxi-xxii), he soon quit using it. The lectures he developed urged Christians to abandon the gap view in favor of “progressive creation”—the same term Silliman had used, although Silliman is not mentioned anywhere in the book. “We believe that the fundamental pattern of creation is progressive creation,” he wrote (Ramm 1954, 113, his italics). While researching his book, Ramm encountered “two traditions in Bible and science both stemming from the developments of the nineteenth century.” On the one hand, there was “the ignoble tradition which has taken a most unwholesome attitude toward science” and relies on poor scholarship (ibid., preface). Although he offered no specific examples, Ramm must have put Rimmer and several other advocates of the gap theory in this camp, despite the fact that he had once held that view himself, having learned it from the Scofield Bible and Rimmer’s works as a young Christian (Numbers 2006, 209). On the other hand, there was also “a noble tradition in Bible and science, and this is the tradition of the great evangelical Christians … who have taken great care to learn the facts of science and Scripture. No better example can be found than that of J. W. Dawson” and others, including Dana, Gray, and Orr. Unfortunately, Ramm, noted, “the noble tradition … has not been the major tradition in evangelicalism in the twentieth century. Both a narrow evangelical Biblicism, and its narrow theology, buried the noble tradition” (ibid., preface). Ramm clearly hoped to persuade conservative Protestants to abandon the gap theory, which no longer had any hope of matching the geological data, and to embrace what he called “concordism because it seeks a harmony of the geologic record and the days of Genesis interpreted as long periods of time.” Two varieties are identified: the standard “age-day” view (as Ramm referred to it) and a “moderate concordism” in which “geology and Genesis tell in broad outline the same story,” but there is no attempt to assign specific geological events to a given “day.” Ramm favored the latter, while stressing that progressive creation “is not theistic evolution, which calls for creation from within with no acts de novo,” yet he also found “a sure but slender thread of theistic evolutionists” among the evangelicals and spoke warmly of them (ibid., 211, 226, 228 and 284). His message did not fall on deaf ears, creating quite a stir among the fundamentalists from whom Ramm was obviously distancing himself while eliciting praise from a thirty-five-year-old Billy Graham. Graham was already drawing criticism from some fundamentalists for being too cozy with the emerging group of “neo-evangelicals” who were in the process of creating the magazine, Christianity Today, and launching a more open-minded type of conservative Protestantism. In that somewhat charged atmosphere, The Christian View of Science and Scripture helped split conservative Protestant scientists and scholars into two groups, one cautiously progressive and the other reactionary. Some of the progressives were members of the American Scientific Affiliation, an organization of Christians in the sciences that had been founded at Moody Bible Institute in 1941, with which Ramm became involved in the late 1940s. Although none of the five founding members was a theistic evolutionist and for at least two decades most members did not accept evolution, by the time Ramm found out about the ASA some influential members had begun to speak favorably about evolution or strongly against various forms of creationism at their meetings and in their journal—to the consternation of some other members. One disgruntled ASA member, a youthful Southern Baptist engineer named Henry M. Morris who taught at Rice Institute (now Rice University) and who greatly admired Rimmer, had recently written a Rimmer-like book, That You Might Believe (1946), that was classified in Ramm’s bibliography as a work “of limited worth due to improper spirit or lack of scientific or philosophic or biblical orientation.” Morris presented the gap theory as a reasonable option, but then he immediately argued against various scientific methods for estimating the age of the earth and endorsed the traditional biblical chronology of a few thousand years; in the second edition he simply deleted the material about the gap view (Numbers 2006, 220). He also defended “flood geology,” the view that the fossil-bearing rocks had been laid down not over millions of years, but all at once in the biblical flood. Morris got this idea from George McCready Price, a self-proclaimed geologist and Seventh-day Adventist who took it in turn from Ellen G. White, the nineteenth-century prophetess whose teachings lay at the core of the Adventist faith. Price had been attacking evolution and modern geology for decades, and fundamentalists regarded him as an authority on those topics—Bryan had tried unsuccessfully to bring him to Dayton as an expert witness—despite the fact that he belonged to a “sect” and lacked scientific credentials. Price’s articles appeared frequently in the Sunday School Times and other fundamentalist periodicals, but even the Catholic Weekly and the prestigious Princeton Theological Review published something of his. Although the fundamentalists did not adopt Price’s young earth and did not usually adopt flood geology either, they shared his commitment to the recent creation of humans and appreciated how he had defended the historicity of the flood and undermined evolution—especially in his monumental work, The New Geology (1923), which Rimmer called “a masterpiece of REAL Science [that] explodes in a convincing manner some of the ancient fallacies of science falsely so called” (Davis 1995, 369). Ramm attributed Price’s popularity among fundamentalists to “one reason alone—that he has stridden forth like David to meet the Goliath of modern uniformitarian geology and that even though the giant has not fallen Price has been slinging his smooth stones for more than forty years” (Ramm 1954, 182). The popularity of Price notwithstanding, Morris’ acceptance of both a young earth and flood geology was unusual for a fundamentalist in the late 1940s. Over the next quarter century, however, both views would become very widely held among fundamentalists, owing to a work he wrote collaboratively with another fundamentalist who did not appreciate Ramm’s book—theologian John C. Whitcomb, Jr., of Grace Theological Seminary in Winona Lake, Indiana. Whitcomb took particular exception to Ramm’s view that the flood had been local to Mesopotamia rather than geologically universal. He met Morris at an ASA meeting held on the Grace campus in 1953, when Morris gave a paper on “Biblical Evidence for a Recent Creation and Universal Deluge.” Previously a defender of the gap view, Whitcomb was persuaded to change his mind. He proceeded to write a doctoral dissertation on the flood, in which he drew heavily on Price. When it was finished in 1957, Whitcomb invited Morris to co-author a book, The Genesis Flood (1961), which effectively launched the modern creationist movement. The Genesis Flood has all of the elements of what would later be called “scientific creationism” (a term that Morris liked but Whitcomb did not): the recent special creation of the universe, the earth, and living things—with apparent age in some cases; the production of the geological strata, including the fossils, in a single, worldwide flood in Noah’s day; and the fall of Adam and Eve, resulting in disease, suffering, and death throughout the animal kingdom. Still in print fifty years later, The Genesis Flood has sold more 300,000 copies in five languages. When the book was received poorly by many ASA members, Morris and several of his friends broke with the ASA in 1963 and formed the Creation Research Society—an organization that requires members to accept the tenets of scientific creationism. Since then several other creationist organizations have appeared. Morris himself founded the Institute for Creation Research in San Diego in 1970; it is now based in Dallas and directed by his son, John D. Morris, who has a doctorate in geological engineering. Although the ICR remains very influential, another creationist organization is probably now even more influential: Answers in Genesis (originally called Creation Science Ministries), founded in 1993 by Ken Ham, a former public school science teacher from Queensland, Australia, for the stated purpose of “upholding the authority of the Bible from the very first verse.” Based in northern Kentucky, AIG operates a large and technically impressive Creation Museum, completed in May 2007 at a cost reported to be about $27 million, that has drawn more than one million visitors in less than three years. Ham’s daily radio feature is broadcast on more than 900 stations and he has appeared on major television networks, including Fox, ABC, CNN, and the BBC. The web sites owned by ICR and AIG are very large, and both organizations market printed materials and DVDs aggressively. Fundamentalist Views Today Fundamentalists today are heavily invested in scientific creationism. The gap view is almost extinct, the day-age view is seen as a dangerous “compromise” with biblical truth, and even “intelligent design” theory is often seen as too theologically minimalist to be acceptable. Several of the larger Christian colleges require science faculty to adhere to “young-earth” creationism, including Cedarville University (Ohio), Bob Jones University (South Carolina), and Liberty University (Virginia), whose founding president, the late Southern Baptist evangelist Jerry Falwell, also founded the Moral Majority. Many Christian day schools teach that creationism is the best, or even the only appropriate, option for students to consider, and the larger publishers catering to homeschoolers have the same basic approach. Although most Protestant denominations do not officially require pastors to accept creationism, in 1998 the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in America, a denomination formed in the 1970s by conservatives who left mainline churches in disputes over biblical inerrancy and the role of women in the church, appointed a committee to study the possibility of making a literal interpretation of the Genesis “days” an article of faith. Although the committee did not make such a recommendation, some important PCA clergy have been creationists, including the late D. James Kennedy, whose radio program had 3.5 million listeners. Theologian R. Albert Mohler, Jr., who helped orchestrate a conservative resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant body in the United States, is strongly committed to creationism. Independent fundamentalist churches usually endorse creationism and often host conferences featuring creationist speakers or showing films produced by ICR or AIG. Many fundamentalists, seeking support for traditional morality in the midst of ongoing “culture wars,” have connected evolution closely with diverse social ills. Morris went so far as to suggest that “Satan himself is the originator of the concept of evolution” (Morris 1974, 75), and Ham blames evolution for racism, pornography, abortion, euthanasia, divorce, and homosexuality—even though all of those things predate Charles Darwin by several millennia. Ironically, many of the most influential and outspoken antievolutionists of the last century—people such as Bryan, Riley, Scofield, Rimmer, and Torrey—would not be allowed to teach at those colleges, prepare curricular materials for those publishers, or preach from those pulpits. Fundamentalist views about science have evolved since the 1920s. The biggest change involves the explicit rejection of the overall attitude displayed by Silliman, Dana, and Dawson. Like Augustine, John Calvin, Johannes Kepler, Francis Bacon, Galileo Galilei and many other Christian thinkers from earlier ages, they viewed the Bible and nature as two “books” by the same Author that had to agree when both were rightly interpreted. Whitcomb has called this idea the “double-revelation theory,” and in a pamphlet written shortly after The Genesis Flood he spelled out its shortcomings. First, it “fails to give due recognition to the tremendous limitations which inhibit the scientific method when applied to the study of origins.” Next, it “overlooks the insuperable scientific problems which continue to plague all naturalistic and evolutionary theories concerning the origin of the material universe and of living things.” Finally, it “underestimates God’s special revelation in Scripture” (1964, 9 and 25). Other creationists have pushed this idea much further, arguing for a sharp distinction between “operation science” (or experimental science) and “historical science.” In their view, the historical sciences (such as geology, paleontology, and cosmology) are not really sciences at all, because we cannot put development of the earth and the universe into a laboratory and repeat the process. Therefore, whenever the conclusions of the historical sciences conflict with the words of God, the only eyewitness of the creation events, we must reject the former in favor of the latter. Even the “big bang” theory, which many conservative Christian writers have seen as highly consistent with a belief in creation ex nihilo, is rejected by creationists as yet one more example of science falsely so called. References

Bryan, William Jennings. 1922. The Menace of Darwinism. New York: Fleming H. Revell. Co. Bugg, George. 1826-27. Scriptural Geology. 2 vols. London: Hatchard and Son. Conklin, Edwin Grant. 1953. Edwin Grant Conklin. In L. Finkelstein (Ed.). Thirteen Americans: Their Spiritual Autobiographies. New York: Institute for Religious and Social Studies, Jewish Theological Seminary of America, pp. 47-76. Davis, Edward B. 1995. The Antievolution Pamphlets of Harry Rimmer. New York: Garland Publishing. Dawson, J. William. 1890. Modern Ideas of Evolution as Related to Revelation and Science. London: The Religious Tract Society. Kellogg, Vernon. 1917. Headquarters Nights: A Record of Conversations and Experiences at the Headquarters of the German Army in France and Belgium. Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press. Livingstone, David N. 1984. Darwin’s Forgotten Defenders: The Encounter Between Evangelical Theology and Evolutionary Thought. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. Marsden, George M. 1983. Creation versus Evolution: No Middle Way. Nature, 305(5935), pp. 571-574. Marsden, George M. 1988. Introduction. In George M. Marsden (Ed.). The Fundamentals: A Testimony to Truth. 4 Vols. New York: Garland Publishing, Vol. 1, n.p. Mathews, Shailer. 1936. New Faith for Old: An Autobiography. New York: Macmillan. Miller, Samuel. 1803. A Brief Retrospect of the Eighteenth Century. New York: T. and J. Swords. Moore, James R. 1979. The Post-Darwinian Controversies: A Study of the Protestant Struggle to Come to Terms with Darwin in Great Britain and America 1870-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Moore, James R. 1981. The Future of Science and Belief: Theological Views in the Twentieth Century. Milton Keynes: The Open University Press. Morris, Henry M. 1974. The Troubled Waters of Evolution. San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers. Numbers, Ronald L. & Thurs, Daniel P. 2011. Science, Pseudoscience, and Science Falsely So-Called. In Peter Harrison, Ronald L. Numbers & Michael H. Shank (Eds.). Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 281-306. Ramm, Bernard. 1954. The Christian View of Science and Scripture. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Silliman, Benjamin. 1829. Outline of the Course of Geological Lectures Given in Yale College. New Haven: Hezekiah Howe. Whitcomb, Jr., John C. 1964. The Origin of the Solar System: Biblical Inerrancy and the Double-Revelation Theory. Phillipsburg, New Jersey: Presbyterian and Reformed Pub. Co. Further Reading Davis, Edward B. 2008. Fundamentalist Cartoons, Modernist Pamphlets, and the Religious Image of Science in the Scopes Era. In C. L. Cohen and P. S. Boyer (Eds.). Religion and the Culture of Print in Modern America. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 175-198. Analyzes how fundamentalists and modernists used print media to reach wide audiences with competing religious interpretations of science during the 1920s. Larson, Edward J. 1997. Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion. New York: Basic Books. Awarded the Pulitzer Prize in history, this book revolutionized our understanding of this famous event. Marsden, George M. 1980. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925. New York: Oxford University Press. A comprehensive, insightful history of fundamentalism. Numbers, Ronald L. 1998. Darwinism Comes to America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Studies the reception of evolution by diverse groups of Americans. Numbers, Ronald L. 2006. The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design. Expanded ed., Cambridge: Harvard University Press. The definitive history of creationism. Porterfield, Amanda. 2006. The Protestant Experience in America. Westport: Greenwood Press. Places scientific creationism and the Scopes trial in the context of fundamentalism, while linking fundamentalism with defenders of biblical authority in earlier years. Whitcomb, John. C., Jr. & Morris, Henry M. 1961. The Genesis Flood: The Biblical Record and Its Scientific Implications. Philadelphia: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co. The most influential creationist book ever published. |