God and Nature Winter 2021

By Ruth Bancewicz (Spring 2015)

Believe it or not, studying little stripy fish is a great way to understand processes that are important to human health. Like many of the organisms that biologists study, zebrafish were chosen for fairly mundane reasons. They are cheap to look after, have a short life cycle, lay large quantities of eggs, and can be bought from any pet shop. Most importantly, the anatomy and chemistry of their bodies is similar to our own. Zebrafish have helped us to understand a number of human diseases, including heart defects and muscle-wasting disorders. They are also surprisingly beautiful close up.

I’ll never forget my first encounter with zebrafish. I was interviewing for a PhD scholarship, and my future supervisor was showing me around the lab. When she took me to the fish room I was surprised to see that zebrafish don’t actually look like their namesakes, because their stripes run horizontally. The adults shimmered and darted around the tanks, and some had spots instead of stripes, or long trailing fins. I could see why these fish are popular aquarium pets, but it was their offspring that had me transfixed.

Believe it or not, studying little stripy fish is a great way to understand processes that are important to human health. Like many of the organisms that biologists study, zebrafish were chosen for fairly mundane reasons. They are cheap to look after, have a short life cycle, lay large quantities of eggs, and can be bought from any pet shop. Most importantly, the anatomy and chemistry of their bodies is similar to our own. Zebrafish have helped us to understand a number of human diseases, including heart defects and muscle-wasting disorders. They are also surprisingly beautiful close up.

I’ll never forget my first encounter with zebrafish. I was interviewing for a PhD scholarship, and my future supervisor was showing me around the lab. When she took me to the fish room I was surprised to see that zebrafish don’t actually look like their namesakes, because their stripes run horizontally. The adults shimmered and darted around the tanks, and some had spots instead of stripes, or long trailing fins. I could see why these fish are popular aquarium pets, but it was their offspring that had me transfixed.

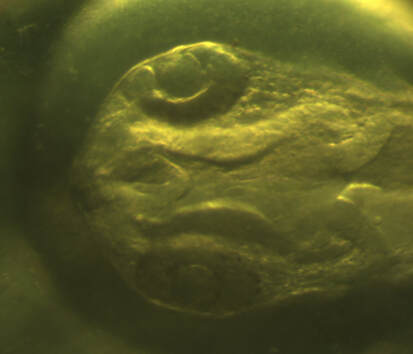

When I looked down a microscope at a dish of wiggling zebrafish larvae, I was – as the Wisconsin-based biologist Jeff Hardin said when he saw his first sea urchin embryo – absolutely hooked. At twenty-four hours old, they are about two and a half millimetres long and almost completely translucent. I could see every detail of their anatomy in minute detail. I could see their hearts pumping, and tiny red blood cells moving through their blood vessels. I could trace the outline of muscle fibres in their tails, and see every detail of their developing eyes. Later on the eye becomes covered in silvery pigment cells, the transparent lens protruding, beautifully rounded and greenish in colour. I was full of questions, and wanted to get to work immediately. I was excited to have three whole years to learn about these beautiful organisms, and I never grew tired of looking at them.

Head of a Zebrafish larva, around 24h, by Ruth Bancewicz.

Everyone in the lab feels a sense of wonder from time to time. Maybe they see something new in an experiment that sparks their curiosity, or they might find a surprising result when they analyze a collection of data. Maybe they just have a few spare minutes to stare at the things they study and become lost in fascination. Each person will come to a different conclusion about what they see and what it points to, but wonder seems to be part of the package in science. It is an experience that raises spiritual questions for some, and enhances faith for others.

Deeper wonder The philosopher Adam Smith thought that learning drives out wonder, and to some extent he’s right. A certain kind of wonder can sometimes be lost in the process of taking things apart. The poet Keats expressed this in his poem Lamia, saying that scientists “unweave a rainbow,” and, “Do not all charms fly at the mere touch of cold philosophy?”

If science causes some to lose their sense of wonder, then how do scientists keep going? I learned the answer to this question from the philosopher and cognitive scientist Margaret Boden, who tells the story of a colleague who was fascinated by circles as a young child. [ii] He collected all sorts of round objects, kept them in a cupboard, and used them as templates for drawing circles. His parents noticed his new hobby and decided to encourage it. They promised him an instrument that could draw circles of any size. Imagining some sort of magical expanding object, he was filled with wonder and excitement and could hardly wait to receive his gift.

On the day the circle-making machine appeared, the boy’s dreams were shattered. The compass he was given was not at all what he had been expecting. It was so simple and boring, and not at all circular. It completely destroyed his love of circles. Boden’s colleague felt such a strong feeling of disillusionment at the time that he remembered it as a “traumatic event in his childhood.” I expect his parents felt terrible too.

As an adult mathematician, however, Boden’s colleague learned to appreciate the elegant simplicity of the compass. Now he understands the mathematical principle behind it, he can see that this instrument is indeed a wonderful thing. Deeper understanding led to deeper wonder. As Boden writes, “When wonder is based on pure ignorance or on error and illusion, it must fade in the light of understanding … But understanding may lead in turn to a new form of wonder, which cannot be so easily destroyed.”

The gift of wonder So where does wonder take us? Einstein thought the most surprising and fascinating thing about the natural world is that we can make sense of it. “… the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility.”[iii] A scientist might start with a jumble of data, but after some patient sorting and calculating they notice a pattern – maybe a potential mathematical description or a link between one process and another. To discover that pattern for yourself is stunning. It was there all along, just waiting to be found.

At times, wrote the Danish historian of science Olaf Pedersen, a scientist who has gone through the process of discovering and making sense of things might feel as if they have invented something. On a more fundamental level though, they have done nothing of the sort. The language used by many people when they describe the moment of breakthrough is that they have found a reality that was always there. The physicist Heisenberg wrote that

when one stumbles upon these very simple, great connections … the whole thing appears in a different light. Then our inner eye is suddenly opened to a connection which has always been there – also without us – and which is quite obviously not created by man.[iv]

Pedersen noticed that the experience of discovery is sometimes so powerful that scientists say they feel as if they have received a gift. The Nobel prize-winning particle physicist Carlo Rubbia described his own feelings of gratitude and wonder in a public lecture.

When we look at a particular physical phenomenon, for example a starry night, we feel deeply moved; we feel within ourselves a message which comes from nature, which transcends it and dominates it … The beauty of nature, seen from within and in its most essential terms, is even more perfect than what appears externally … I feel curiosity and am honoured to be able to see these things, fortunate, because nature is in fact a spectacle that is never exhausted.[v]

A gift implies a giver, and though Pedersen doesn’t feel it should be used as an apologetic argument, the theological connection has been made. A deep sense of wonder is not evidence for God, but it might get us thinking beyond what we can see in front of our noses. Neither Heisenberg nor Einstein believed in God,[vi] but they both believed that there is a reality beyond science, and they used spiritual language to describe it.

Faith, science and wonder. The theologian and former biophysicist Alister McGrath has described three ways in which we can experience wonder at nature.[vii] First, there is the sense of “immediate wonder” that we can all experience in response to natural beauty. This type of wonder doesn’t require any special knowledge, there is no theoretical reflection, and no philosophizing. This is pure perception, before any thinking happens, as when I saw my first zebrafish larvae.

Next, if immediate wonder leads to scientific exploration, we have the privilege of experiencing even more wonder as we see how incredible it all is: more highly organized and even more beautiful than it seemed at first. This “derived wonder” at the elegant simplicity of mathematical or theoretical representations of reality is the deeper or informed wonder Boden’s colleague and many others have experienced. McGrath’s final type of wonder is spiritual or theological. It is another kind of derived wonder, provoked by “what the natural world points to”.[viii]

Celia Deane-Drummond began her career as a lecturer in plant science, and is now Professor of Theology at the University of Notre Dame in the USA. Deane-Drummond thinks that wonder drives us to learn and develop wisdom because it marks out the limits of our own understanding. Discovering something intriguing prompts us to find out more, leading to wisdom or knowledge. Wonder can also lead us to other realities, because intense scientific or philosophical enquiry may show the limits of what is natural or material. This prompts people to ask more philosophical questions.[ix]

Ultimately, says Deane-Drummond, wonder informed by wisdom can lead to spiritual exploration. The question is, does scientific wonder actually point to God? The answer is yes, but not very far. Einstein and Heisenberg had a sense of something “out there,” but their scientific exploration didn’t take them any further. Creation isn’t God – it just reflects something of God’s character. So there are limits to the number of places that a journey from science to religion can take you, but it can be a very good starting point for a fruitful discussion.

For more on this topic read Ruth’s book, God in the Lab: How science enhances faith (Kregel/Monarch, 2015)

References:

[i] Veronica van Heyningen, “Gene games of the Future” (Book Review), <i>Nature</i> 408 (2000).

[ii] Margaret Boden, “Wonder and Understanding”, <i>Zygon</i> 20 (1985), pages 391–400.

[iii] Bersanelli & Gargantini, <i>From Galileo to Gell-Mann: The Wonder That Inspired the Greatest Scientists of All Time</i>, page 155.

[iv] Olaf Pedersen, “Christian belief and the fascination of science” in eds. Robert John Russell, William R. Stoeger & George V. Coyne, <i>Physics, Philosophy and Theology: A Common Quest for Understanding</i>, Vatican City State: Vatican Observatory, 1988, pages 125–140.

[v] Bersanelli & Gargantini, <i>From Galileo to Gell-Mann: The Wonder That Inspired the Greatest Scientists of All Time</i>, page 8.

[vi] Einstein’s beliefs are described by Max Jammer, <i>Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology</i>, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999, pages 67–75; Heisenberg’s by Enrico Cantore, <i>Scientific Man: The Humanistic Significance of Science</i>, ISH Publications, 1977, pages 117-118; Rachel Carson was deeply spiritual but didn’t hold to any particular religion, and she did believe in God, see Frankenberry, <i>The Faith of Scientists</i>, pages 197–221; I can find no evidence of Carlo Rubbia’s views about God.

[vii] Alister E. McGrath, “Has Science Eliminated God?”, <i>Science and Christian Belief</i> 17 (2005): 115–35.

[viii] McGrath, “Has Science Eliminated God?”, <i>Science and Christian Belief</i>, pages 115–35.

[ix] Deane-Drummond, <i>Wonder and Wisdom: Conversations in Science, Spirituality and Theology</i>.

[x] Celia Deane-Drummond, “Experiencing Wonder and Seeking Wisdom”, <i>Zygon</i> 42 (2007): 587–590.

Ruth Bancewicz is Church Engagement Director at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where her remit is to help UK churches interact with science in a helpful way. She studied Genetics at Aberdeen and Edinburgh Universities, and spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology in Edinburgh, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. She joined The Faraday Institute when it was founded in 2006, with the aim of developing resources for churches – the first of which were the Test of FAITH materials. Ruth is a member of Christians in Science and a Fellow of their US counterpart, the American Scientific Affiliation. She is a member of City Church Cambridge, and is currently studying theology with Spurgeons College, London.

Head of a Zebrafish larva, around 24h, by Ruth Bancewicz.

Everyone in the lab feels a sense of wonder from time to time. Maybe they see something new in an experiment that sparks their curiosity, or they might find a surprising result when they analyze a collection of data. Maybe they just have a few spare minutes to stare at the things they study and become lost in fascination. Each person will come to a different conclusion about what they see and what it points to, but wonder seems to be part of the package in science. It is an experience that raises spiritual questions for some, and enhances faith for others.

Deeper wonder The philosopher Adam Smith thought that learning drives out wonder, and to some extent he’s right. A certain kind of wonder can sometimes be lost in the process of taking things apart. The poet Keats expressed this in his poem Lamia, saying that scientists “unweave a rainbow,” and, “Do not all charms fly at the mere touch of cold philosophy?”

If science causes some to lose their sense of wonder, then how do scientists keep going? I learned the answer to this question from the philosopher and cognitive scientist Margaret Boden, who tells the story of a colleague who was fascinated by circles as a young child. [ii] He collected all sorts of round objects, kept them in a cupboard, and used them as templates for drawing circles. His parents noticed his new hobby and decided to encourage it. They promised him an instrument that could draw circles of any size. Imagining some sort of magical expanding object, he was filled with wonder and excitement and could hardly wait to receive his gift.

On the day the circle-making machine appeared, the boy’s dreams were shattered. The compass he was given was not at all what he had been expecting. It was so simple and boring, and not at all circular. It completely destroyed his love of circles. Boden’s colleague felt such a strong feeling of disillusionment at the time that he remembered it as a “traumatic event in his childhood.” I expect his parents felt terrible too.

As an adult mathematician, however, Boden’s colleague learned to appreciate the elegant simplicity of the compass. Now he understands the mathematical principle behind it, he can see that this instrument is indeed a wonderful thing. Deeper understanding led to deeper wonder. As Boden writes, “When wonder is based on pure ignorance or on error and illusion, it must fade in the light of understanding … But understanding may lead in turn to a new form of wonder, which cannot be so easily destroyed.”

The gift of wonder So where does wonder take us? Einstein thought the most surprising and fascinating thing about the natural world is that we can make sense of it. “… the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility.”[iii] A scientist might start with a jumble of data, but after some patient sorting and calculating they notice a pattern – maybe a potential mathematical description or a link between one process and another. To discover that pattern for yourself is stunning. It was there all along, just waiting to be found.

At times, wrote the Danish historian of science Olaf Pedersen, a scientist who has gone through the process of discovering and making sense of things might feel as if they have invented something. On a more fundamental level though, they have done nothing of the sort. The language used by many people when they describe the moment of breakthrough is that they have found a reality that was always there. The physicist Heisenberg wrote that

when one stumbles upon these very simple, great connections … the whole thing appears in a different light. Then our inner eye is suddenly opened to a connection which has always been there – also without us – and which is quite obviously not created by man.[iv]

Pedersen noticed that the experience of discovery is sometimes so powerful that scientists say they feel as if they have received a gift. The Nobel prize-winning particle physicist Carlo Rubbia described his own feelings of gratitude and wonder in a public lecture.

When we look at a particular physical phenomenon, for example a starry night, we feel deeply moved; we feel within ourselves a message which comes from nature, which transcends it and dominates it … The beauty of nature, seen from within and in its most essential terms, is even more perfect than what appears externally … I feel curiosity and am honoured to be able to see these things, fortunate, because nature is in fact a spectacle that is never exhausted.[v]

A gift implies a giver, and though Pedersen doesn’t feel it should be used as an apologetic argument, the theological connection has been made. A deep sense of wonder is not evidence for God, but it might get us thinking beyond what we can see in front of our noses. Neither Heisenberg nor Einstein believed in God,[vi] but they both believed that there is a reality beyond science, and they used spiritual language to describe it.

Faith, science and wonder. The theologian and former biophysicist Alister McGrath has described three ways in which we can experience wonder at nature.[vii] First, there is the sense of “immediate wonder” that we can all experience in response to natural beauty. This type of wonder doesn’t require any special knowledge, there is no theoretical reflection, and no philosophizing. This is pure perception, before any thinking happens, as when I saw my first zebrafish larvae.

Next, if immediate wonder leads to scientific exploration, we have the privilege of experiencing even more wonder as we see how incredible it all is: more highly organized and even more beautiful than it seemed at first. This “derived wonder” at the elegant simplicity of mathematical or theoretical representations of reality is the deeper or informed wonder Boden’s colleague and many others have experienced. McGrath’s final type of wonder is spiritual or theological. It is another kind of derived wonder, provoked by “what the natural world points to”.[viii]

Celia Deane-Drummond began her career as a lecturer in plant science, and is now Professor of Theology at the University of Notre Dame in the USA. Deane-Drummond thinks that wonder drives us to learn and develop wisdom because it marks out the limits of our own understanding. Discovering something intriguing prompts us to find out more, leading to wisdom or knowledge. Wonder can also lead us to other realities, because intense scientific or philosophical enquiry may show the limits of what is natural or material. This prompts people to ask more philosophical questions.[ix]

Ultimately, says Deane-Drummond, wonder informed by wisdom can lead to spiritual exploration. The question is, does scientific wonder actually point to God? The answer is yes, but not very far. Einstein and Heisenberg had a sense of something “out there,” but their scientific exploration didn’t take them any further. Creation isn’t God – it just reflects something of God’s character. So there are limits to the number of places that a journey from science to religion can take you, but it can be a very good starting point for a fruitful discussion.

For more on this topic read Ruth’s book, God in the Lab: How science enhances faith (Kregel/Monarch, 2015)

References:

[i] Veronica van Heyningen, “Gene games of the Future” (Book Review), <i>Nature</i> 408 (2000).

[ii] Margaret Boden, “Wonder and Understanding”, <i>Zygon</i> 20 (1985), pages 391–400.

[iii] Bersanelli & Gargantini, <i>From Galileo to Gell-Mann: The Wonder That Inspired the Greatest Scientists of All Time</i>, page 155.

[iv] Olaf Pedersen, “Christian belief and the fascination of science” in eds. Robert John Russell, William R. Stoeger & George V. Coyne, <i>Physics, Philosophy and Theology: A Common Quest for Understanding</i>, Vatican City State: Vatican Observatory, 1988, pages 125–140.

[v] Bersanelli & Gargantini, <i>From Galileo to Gell-Mann: The Wonder That Inspired the Greatest Scientists of All Time</i>, page 8.

[vi] Einstein’s beliefs are described by Max Jammer, <i>Einstein and Religion: Physics and Theology</i>, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999, pages 67–75; Heisenberg’s by Enrico Cantore, <i>Scientific Man: The Humanistic Significance of Science</i>, ISH Publications, 1977, pages 117-118; Rachel Carson was deeply spiritual but didn’t hold to any particular religion, and she did believe in God, see Frankenberry, <i>The Faith of Scientists</i>, pages 197–221; I can find no evidence of Carlo Rubbia’s views about God.

[vii] Alister E. McGrath, “Has Science Eliminated God?”, <i>Science and Christian Belief</i> 17 (2005): 115–35.

[viii] McGrath, “Has Science Eliminated God?”, <i>Science and Christian Belief</i>, pages 115–35.

[ix] Deane-Drummond, <i>Wonder and Wisdom: Conversations in Science, Spirituality and Theology</i>.

[x] Celia Deane-Drummond, “Experiencing Wonder and Seeking Wisdom”, <i>Zygon</i> 42 (2007): 587–590.

Ruth Bancewicz is Church Engagement Director at The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, where her remit is to help UK churches interact with science in a helpful way. She studied Genetics at Aberdeen and Edinburgh Universities, and spent two years as a part-time postdoctoral researcher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology in Edinburgh, while also working as the Development Officer for Christians in Science. She joined The Faraday Institute when it was founded in 2006, with the aim of developing resources for churches – the first of which were the Test of FAITH materials. Ruth is a member of Christians in Science and a Fellow of their US counterpart, the American Scientific Affiliation. She is a member of City Church Cambridge, and is currently studying theology with Spurgeons College, London.