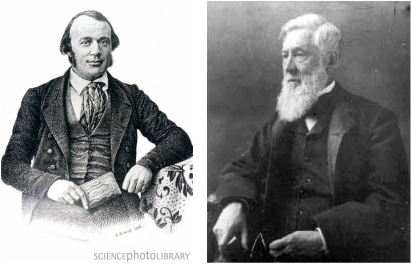

One slice of the zoology narrative: a portrait of Louis Agassiz Louis Agassiz and Asa Gray

by Thomas Burnett

Nothing can be prettier than the smaller kinds of jellyfishes. Their structure is so delicate, yet so clearly defined, their color so soft, yet often so brilliant, their texture so transparent, that you are tempted to say that nature has done her finest work in the sea rather than on land." — Elizabeth Agassiz Any discussion of American science must include Louis Agassiz, the most prominent scientist in North America during the 19th century. Originally born in Switzerland, Agassiz moved permanently to the United States in 1848 after Harvard University offered him a professorship of Zoology and Geology. At the founding of the National Academy of Sciences, Agassiz was named one of its charter members and served as its foreign secretary from 1863-73. Like George Ellery Hale many decades later, Agassiz was a great institution builder. He tirelessly raised funds to construct the Museum of Comparative Zoology, a research museum that recently celebrated its 150th anniversary. Agassiz was also a charismatic lecturer who inspired two generations of Americans to study natural history. He had an impressive track record of training graduate students, many of whom became future leaders of their fields. At the same time, Agassiz had a strong and inflexible personality that caused conflict and consternation within the scientific community. Despite his great legacy of institution building and teaching, Agassiz was also “an egotist who appropriated the work of others and refused to give up an obsolete worldview.” Relationship to Asa Gray During his 25 years at Harvard, Agassiz was colleagues with botanist Asa Gray. Though they were both leaders of their respective fields, these two men were strikingly different. Agassiz spent a great deal of time giving popular lectures to general American audiences, which garnered him a great deal of fame, but did not endear him to his scientific colleagues. Gray took the opposite approach, rarely speaking publically and instead focused his energy on discourse within the scientific community. Most strikingly, Agassiz was a fierce opponent of Darwin’s theory and maintained this position until his death in 1873. Asa Gray, on the other hand, helped evolutionary theory gain support among the American scientific community from the very beginning. In addition to their conflict over scientific matters, Agassiz and Gray had strong differences in personal philosophies. Whereas Asa Gray maintained the common ancestry of all human beings, Agassiz denied the common origin of our species, arguing instead that different races were separately created. Regardless of Agassiz’s intent, it played directly into the hands of pro-slavery advocates. Given his strong opposition to evolution, Agassiz was a strong ally of conservative Christian critics of Darwin. But their alliance was strange because Agassiz himself was a Unitarian, a religous community that denied the central tenets of Christianity, including the divinity of Christ. Asa Gray, on the other hand, accepted traditional Christian theology as well as Darwin's evolutionary theory. Though Agassiz spoke often of the role of the Creator in the development of organisms, he was not at all interested in a literal reading of the book of Genesis. One of his students noted, in April 1860, "Splendid lecture by Prof this morning on the absurdity of believing that Adam and Eve were the first created and the only ones. It was a masterly lecture and was listened to with great attention." Louis Agassiz should therefore not be associated with "scientific creationists" of our day. Scientific achievements It would not be fair to treat Louis Agassiz simply as an adversary to the scientific progress of evolutionary theory. Among his many contributions, he was the first scientist to propose that the Earth had experienced a great ice age. In 1840, his two volume work Etudes sur les glaciers (study on glaciers) explained the movement and effects of glaciers in the European Alps. This theory has become a central tenet of the modern earth sciences. During Agassiz’s tenure at Harvard, the 10-year period from 1854 to 1864 was the most fruitful of his career. His "Essay on Classification" (1857) established a framework to better understand the relationships between diverse species. Two years later Agassiz founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology in 1859 as the center of his classification research initiative. When we think about science museums, most of us imagine a space where schoolchildren experience the majesty of nature, then return to tell their parents that they want to study dinosaurs. Public museums such as these are important centers of informal science education, but Louis Agassiz’s research museum was designed for a very different audience: professional scientists. Agassiz’s vast array of specimens and fossils were organized in a way to better understand morphology, embryology, and geographical distribution. His museum provided a foundation for scientific research of the highest quality. Agassiz preached endlessly on the great things that could be achieved through his museum if only he received sizable funding for specimens, books, assistants, curators, collecting trips, and heavily-illustrated publications. He convinced philanthropists, college administrators, state legislators, and hundreds of citizens to financially support his vision, variously appealing to their religious sensibilities, patriotism, hunger for novelty, and the desire for scientific progress.  Alepocephalus at the Museum of Comparative Zoology

Great mentor of students

While directing his museum, Agassiz trained a generation of young scientists to carry on his vision. He insisted that his students learn to think for themselves rather than rely on previous research or an authority like Agassiz. One of his former students recalled that when he first began working with Agassiz, his mentor brought him a rusty tin pan containing a fish. Agassiz told him to study the fish, but not to read anything about it or speak to anyone. He sat alone for an entire week before Agassiz asked him to explain what he saw. After listening to him for an hour, Agassiz simply said, "That is not right," and walked away. Though this incident is rather extreme, this style of teaching became known as the "case study method" and widely adopted throughout educational institutions. Agassiz stressed the importance of direct observation, both in the museum and in the field. For his students, zoology was not simply an indoor study of dead specimens, but a living enterprise of scientific exploration throughout the world. Agassiz knew that by employing students instead of full-time staff, he could get highly qualified workers at bargain rates. But the students also benefitted from this arrangement, since they would learn far more in a research environment than from a lecture or textbook. To take just one example, Agassiz's student Joseph LeConte was asked to join the faculty of the newly founded University of California in 1869. LeConte became UC-Berkeley's first professor of geology, natural history, and botany, and held this position for the rest of his life. Natural classification schemes In Agassiz's “Essay on classification,” he states that when classification is done correctly, it reveals the connections between the great varieties of life scattered across the planet. Agassiz insisted that his groupings were not artificially constructed for human convenience, but represented naturally occurring relationships between species. To distinguish between natural and artificial classification schemes, let’s consider an example from geography. “States” and “countries” are purely human inventions that we ascribe to our environment. On the other hand, “islands” and “mountains” are natural features of the earth. In a similar fashion, Agassiz believed that there were four naturally occurring types of animals: vertebrates (those with backbones), molluscs (such as clams and mussels), articulates (segmented bodies like centipedes), and radiates (symmetrical creatures like jellyfish). Individual species of animals fell into one of these categories, and each group shared many characteristics. Not only did Agassiz discover shared traits between seemingly unrelated creatures, he also found links between the embryonic forms of one species to embryos and adults of other species, including extinct fossil forms. Agassiz's entire museum was arranged by these patterns of organic similarity, as shown by morphology, embryology, paleontology, and geographic distribution. Clearly, there were underlying forces in Nature that unified the species on our planet. Discovering the cause of these forces was the great challenge of 19th century biology. Legacy How should we judge Louis Agassiz’s legacy? Since he rejected Darwin’s theory, many critics have dismissed him as a close-minded conservative who hindered scientific progress. But as we have seen here, this view is simplistic and historically inaccurate. Agassiz was a powerful institution builder and popularizer of science. His specimen collection was vast and his research program was robust. When evolutionary theory supplanted his worldview, thousands of “facts” that Agassiz had established were reinterpreted and subsumed into the next generation of scholarship. Though he obstinately opposed the innovative theories of his peers, Louis Agassiz’s prodigious research was not in vain. The lumpiness of science There is a strong tendency to exalt scientists who formulate powerful theories—Galileo, Newton, Darwin, and Einstein have achieved immortality in our culture. At the same time, we tend to forget investigators like Louis Agassiz and Asa Gray who spent most of their careers conducting empirical research. In doing so, we distort our understanding of science. Without painstaking commitments to experiments, collections, and other highly repetitive activities, it is impossible to determine whether bold scientific theories are supported by facts or by fiction. Historian Mary Winsor characterizes science in an insightful way: "Science is a lumpy mixture of activities that range from the fact-collecting end of the scale to the theorizing end. Individual scientists may work at different points of the scale at different times. Far from being destroyed, the scale is made richer by the recognition that there can be no bare fact not infected by theory, and no pure theory independent of facts. Balance is achieved, as always with human affairs, imperfectly, through struggle and contradiction, through opposition and compromise.” Just as challenges and obstacles spark technical innovation, confusion and conflict among scientists promote creative understanding of perplexing phenomena. Agassiz made his mark by building a research institution at Harvard that has endured for 150 years, and he assembled a massive amount of data that the scientific community had to account for. Louis Agassiz remains a controversial figure, but his conflicts with his peers challenged them to assemble massive empirical support for their new theories and push biology into a new era. — Thomas Burnett Authors's Note: I am greatly indebted to the research of historian Edward Lurie, particularly his biography Louis Agassiz: A Life in Science, from which I relied heavily in this essay. |

|