Evolution and Imago Dei

Michaelangelo's famous depiction of "imago dei"

By Sy Garte

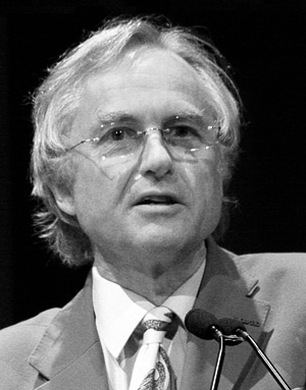

The concept of Imago Dei is under attack. Some militant atheists have tried to use evolutionary theory (among other things) to show that there is nothing at all special about human beings. Mistakenly thinking that science supports this view, some Christian philosophers have put forward the idea that Imago Dei is not limited to the creation of human beings but to all biological creation. I believe that this is not only bad theology, but also terrible science. The rest of the essay will explain why I maintain the second part of that sentence. Not only the biological characteristics of each individual animal, but also individual and group behavior, are ultimately of genetic origin. Animal behavior, like the mating dances of birds, the signaling of bees and ants, the howling of wolves, the family structures of lions, are all examples of behaviors that do not change without a change in genotype. There are exceptions to this rule, and they are all the result of human action. Man, himself, is an exception to the primacy of genetics on behavior. The behavioral phenotype (or visible characteristics of organisms) of human societies has been changing continuously for at least 40,000 years, and while the direction of that change has been constant, the rate of change has been increasing in an exponential manner. At the same time, there have been very few changes in genotype to account for these phenotypic modifications. Humans have also brought about behavioral phenotype changes in domesticated species like dogs and cattle, through training, genetic selection, and breeding, and in some wild animals by environmental alterations. To our knowledge, we are the only species that has done this. Our evolution is no longer genetic, but cultural. And our cultural evolution is driven not by our genes but by our unique brains. The ordinary processes of genetic evolution gave us these brains, but then the brains took over. As a result, the way we live is completely different from the way human beings lived 40,000 years ago. It is different from the way human beings lived 400 years ago, and even 4 years ago. For all other species, this is not the case. From what we can tell, the chimpanzees of today live exactly as they did 4 million years ago.  Dawkins agrees humans have outgrown natural selection

It is true that other animals can solve problems, show altruism, make pictures, communicate, have emotions, maintain social structures and do “all” the things that humans do. The neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky has discussed striking new findings on the ways humans are not as unique as we used to think we are. But for each example of how other animals can do what we do, Sapolsky also provides the evidence of how we remain exceptional. In some cases, this uniqueness seems to be a matter of degree, in that we do so many things so much better than our closest animal relatives. But in other cases, those quantitative differences amount to a, emergent, qualitative effect.

Clearly, what humans do that no other living creature does is change. Humans learn and teach. Humans create and build. Humans progress and investigate. Humans use their huge and complex brains to overcome biological limitations imposed by a genome that changes very, very slowly. Other hominids in our own lineage might have had some ability to transform their species, but not enough to help them survive. Early human precursors in the genus homo were quite fragile as biological entities. They had bad eyesight, were slow and awkward, gave birth rarely and with difficulty. Most homo and earlier Australopithecine species never had very large populations, and they all went extinct relatively quickly, compared to their nearest relatives, the great apes. We are the only surviving member of the genus homo. After spreading throughout the planet, modern humans never stopped changing their own behavioral phenotype through will, imagination, creativity, consciousness and intelligence. As a result of these cultural changes, some aspects of human biology have changed as well. We live twice as long as we used to; we have new diseases, and have escaped some old ones. From agriculture, to cities, to empires, to religion, science, architecture, and use of technology, humans have continually changed themselves and their environment independently of their genes. The idea that humans are uniquely able to overcome the limitations imposed on all other species by natural selection of selfish genes is not limited to those of Christian faith. None other than Richard Dawkins agrees. In a fascinating video on the origin of human altruism, Dawkins says: “As Darwin recognized, we humans are the first and only species able to escape the brutal force that created us, natural selection…. We alone on earth have evolved to the point where we can…overthrow the tyranny of natural selection.” So while the concept of human exceptionalism is consistent with Christian values, the staunch atheist, and foremost Darwinian evolutionist alive today, agrees that humans have gone beyond the laws that govern other creatures. Yes, other animals can appear to think, reason, emote and worry. We can teach them all kinds of things. But they don’t teach each other anything new. Their phenotypes are slaves to their genes. We, and only we, are free. That might be one definition of Imago Dei, but there are certainly others, especially related to our connection with God. A while ago, I was driving from New York toward Washington on the New Jersey Turnpike, listening to a book by PD James on tape. As I drove past the toll barrier at the Delaware Memorial Bridge, it suddenly dawned on me that I was driving a very large, heavy machine at about 80 miles an hour over a beautiful and elaborate structure, and had then gone through the toll barrier without stopping, because my EZ PASS device had sent a signal to the scanning device which allowed the toll to be automatically deducted from my bank account. And while I was doing this, I was listening to a British actress of amazing talent perform a reading of an elaborate and detailed mystery story. The power of the reading and of the original writing had transported my consciousness from New Jersey to the Dorset countryside, so beautifully described by Ms. James. And I thought about how amazing all of this is. No primate before the last hundred years or so ever moved at speeds even a fraction of how fast I was traveling, and yet somehow I had no difficulty or fear of doing so. And look at what my fellow humans have made. A lovely car, with a complex engine—what would our ancestors think of an automobile? And that whole EZ Pass thing. What would my father think of that? What incredible technology we have. And what talent. That actress, who brings the written words to life with her voice. And the writer, the one who thinks of the story. Why can we tell such great stories in the first place? How can my mind deal with all of this as if it is just an ordinary thing in our world, (which if course it is)?. There is nothing at all unusual about a man driving on a highway listening to a taped novel. But that’s only because we are thinking in terms of OUR world, the human world. I would submit that the 20 or 30 amazing phenomena (some of which I have elaborated above) that are included in that simple scenario, are, in any sort of natural world, miraculous. The fact that we don’t see them as such means simply that we are used to miracles, and we call them human nature. I know that I am a primate. A hominid, to be precise. I need food and water. I crave a mate and shelter. I like security and I am wary of danger. I also am very aware of my evil side, and of the evil history of my fellow beings. We hominids are selfish and greedy; we can be violent and defensive. We can be uncaring about others and the environment in which we live. And yet, still a hominid, I find myself not staring out at the rain from my cave, wondering when I will eat next, but driving a large machine at impossible speed, listening to the voice of a woman who is not actually anywhere near me, act out a story composed by another woman. Then all of this is interrupted by a third woman who calls me on my cell phone which I answer using the earpiece of my Bluetooth devise. I hear the voice of the woman I love, and we speak, I make some jokes, hear her laughter. I find this to be a wonderful thing, this being human. And I am very thankful to my Creator. |