Why the Church Needs Intersectional Feminism: On waking up

By Emily Herrington

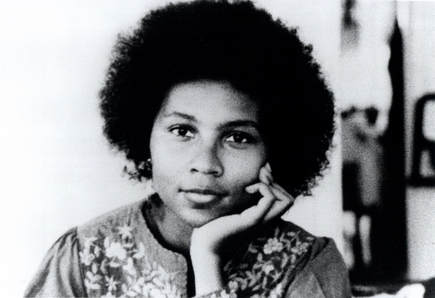

Writer, activist, and race scholar bell hooks in 1988 Writer, activist, and race scholar bell hooks in 1988

"The parables were not earthly stories with heavenly meanings but earthy stories with heavy meanings, weighted down by an awareness of the workings of exploitation in the world of their hearers. … Instead of reiterating the promise of God’s intervention in human affairs, they explored how human beings could respond to break the spiral of violence and cycle of poverty created by exploitation and oppression. The parable was a form of social analysis every bit as much as it was a form of theological reflection.”

~ William R. Herzog II, Parables as Subversive Speech: Jesus as Pedagogue of the Oppressed Some of the articles in this edition of God & Nature magazine discuss our heritage in Christian theology, especially its rather unique emphasis on accepting, with open arms, all who wish to participate. Christians disagree worldwide on the necessary beliefs and traditions of the faith, what constitutes “salvation,” and how to exercise the wisdom of the commandments. But there is almost universal agreement among Christians that Jesus was a healer and a welcomer of the invisible and oppressed. The central argument of this essay is that, like much of feminist thought, Jesus’s story is dangerous to dominant-group narratives of becoming (especially nationalistic, intolerant, or “whitewashed” ones). The feminist project of promoting equality is, in turn, augmented by a commitment to live as Christ. It is intersectional feminism in particular that I think can bring us into productive conversations. Intersectionality is a concept that rose out of black feminist thought, although there is some disagreement as to which thinker or group of thinkers had the most influence on its early development. Law and civil rights scholar Kimberle Crenshaw was an early thinker in the movement; in a recent interview she describes intersectionality as, “the idea that we experience life, sometimes discriminations, sometimes benefits, based on a number of different identities that we have.” Crenshaw says the term “intersectionality” was inspired by a case where she was working with black women who were being discriminated against— “not just as black people and not just as women,” she says, “but as black women.” Intersectionality became a metaphor to describe the unique circumstances of those who face discrimination from several sources or angles simultaneously. The concept of “interlocking systems of oppression” is at the core of intersectional theory. Mechanisms of oppression in our society are, according to Crenshaw, “colliding in ways we don’t really anticipate and understand. So ‘intersectionality’ is basically meant to help people think about the fact that discrimination can happen on the basis of several different factors at the same time, and we need to have a language and an ability to see it, in order to address it.” Patricia Hill Collins, a prominent intersectional theorist and professor of sociology, describes the vectors of discrimination that many people, today, must navigate in Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment: “Race, class, and gender represent the three systems of oppression that most heavily affect African-American women. But these systems and the economic, political, and ideological conditions that support them may not be the most fundamental oppressions, and they certainly affect many more groups than Black women. Other people of color, Jews, the poor white women, and gays and lesbians have all had similar ideological justifications offered for their subordination. All categories of humans labeled Others have been equated to one another, to animals, and to nature.” We all belong to the same traumatic history, but some feel the lasting effects of this history more personally, painfully, and disruptively than others. Intersectional feminism gives the user conceptual tools for engaging difference in a world that is complicated in its science and its history, and which feels immanently precarious to many groups of people. The “grid metaphor” of interlocking systems of oppression is spatial and easy to understand, which is partly why scholars from social science to medicine and the humanities have embraced intersectionality. Indeed, it is increasingly assumed that interlocutors in graduate-level academic conversations will come to the table already familiar with its basic concepts. The influence of intersectionality has been less visible, however, in academic conversations on science and Christian faith. A case study close to home: At a recent ASA meeting in Azusa we collectively celebrated the passage of women into visibility over the course of ASA’s 75-year history. This more inclusive trajectory was presented as an unqualified good; no one who spoke at the meeting felt the need to restate arguments about the rights of women to participate in intellectual discourse, and the value they bring to these conversations. The persistent nods to feminism and the tepid embrace of women’s rights at this meeting was not, however, an embrace of intersectional feminism and other more capacious articulations of the need for diversity, because a quick scan of attendees revealed an audience overwhelmingly white, and this fact was not discussed. It was omitted from the formal ASA histories and retrospectives (where inclusion of women was celebrated), and it continues to be omitted from frank discussion at informal ASA events. The authenticity and ethical merits of conversations on topics like human nature, theology, appropriate technologies, health, medicine, and environmental stewardship, suffer when diversity suffers. Familiar lessons from evolutionary theory should be enough to make us pause here. As Corina Newsome, an environmentalist and animal keeper at the Nashville Zoo, says in an interview in this edition of God & Nature, “homogeny can be dangerous…if everyone is the same (in a population) that species is at risk because they’re more susceptible to being wiped out by a single disease or trigger they’re vulnerable to, but if you have this richness of diversity, you are much more robust.” Corina goes on to make a poignant connection between the predicament of homogeny and cultural white-washing, “If you have everyone offering opinions from the same perspectives, there’s a good chance you’ll miss the answer to the problem, but if you have a diverse (group of) people offering perspectives and ideas and answers from a variety of different backgrounds, there’s a much better chance you’ll come across the answer to whatever problem you’re looking to solve.” Also in this edition of God & Nature magazine, Josh Swamidass argues that we cannot afford to ignore our complicity in the segregation of science and faith. Ciara Reyes’ interview with Carla Ramos and my interview with Carolyn Finney sketch a few arguments as to why white Christians like me need to make the issue of racial disparities in our churches and professional communities our own. At the core of all these arguments is the question of how to love. How creative can we be when imagining the ASA’s audience and the demographics of its future membership? If we can no longer ignore race in our personal meetings and academic offerings, how—and with whose input—should we go about identifying our values around recruitment, programming, and publishing? I think we as committed “practicing” Christians and as science enthusiasts should do what we can to be welcoming and to facilitate ease of participation by black scholars and other minorities in ASA offerings and in the academy in general. Diversity initiatives and support for scholars of color (at the very least) are necessary in this moment. On a more private and interpersonal basis, we can: ~ Lean into the tensions of racial difference and culpability in our conversations and recognize/ acknowledge unearned privilege and access. ~ Be more intentional and respectful with our words, especially when representating Others. ~ Read. Carolyn Finney emphasizes this vital aspect of the work at the end of our interview in this edition. And Dr. Lisa Corrigan, author of Prison Power: How Prison Influenced the Movement for Black Liberation has efficiently remarked: “You can’t be woke if you don’t read.” I have worked with my good friend Heather Hyden, an anti-racist community development activist in Lexington, Kentucky, and the author of a powerfully moving essay and poem in this edition, to conclude this argument with a list of readings for anyone who is intrigued by the above and would like to consult some references, or who enjoys sharpening their wit on wise and challenging literature. Many of the recent titles have Kindle and Audiobook options and most are available at local and university libraries. We have tried to list by genre for ease of navigation, but many of the works span two or more of the categories listed here. Of course, the titles below are only a small sample of the relevant literature. Theory bell hooks: Feminism is for Everybody Angela Davis: Women, Race and Class Leila Ahmed: Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate Judith Butler: Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity Gloria Anzaldua: Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza Ta-Nehisi Coates: Between the World and Me Social science/ History/ Geography Carolyn Finney: Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors Michelle Alexander: The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness Joy de Gruy: Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America's Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing Susan Stryker: Transgender History: The Roots of Today's Revolution James C. Wilson and Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson: Embodied Rhetorics: Disability in Language and Culture Theology Phyllis Trible: Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives Cheryl Townsend Gilkes: If It Wasn't for the Women: Black Women's Experience And Womanist Culture In Church And Community Alice Walker: The Color Purple Gustavo Gutierrez: A Theology of Liberation Fiction and Poetry Toni Morrison: Beloved James Baldwin: Go Tell It on the Mountain Frank X Walker: Affrilachia Claudia Rankine: Citizen: An American Lyric On teaching Paulo Friere: Pedagogy of the Oppressed and William R Herzog: Parables as Subversive Speech: Jesus as Pedagogue of the Oppressed Medical ethnographies/Illness narratives: Anne Fadiman: The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures (The audiobook is wonderful) Audre Lorde: The Cancer Journals |

Emily Ruppel Herrington is a PhD candidate in communication and a master's student in bioethics at the University of Pittsburgh, with focus areas in rhetoric of science, STS, feminist theory, and oral history.

Prior to her doctoral work, Emily studied poetry at Bellarmine University in Louisville (B.A. '08) and science writing at MIT (M.S. '11). She has spent several years working as a professional writer and editor for academic and popular outlets; among them, God & Nature magazine has been a favorite project. |