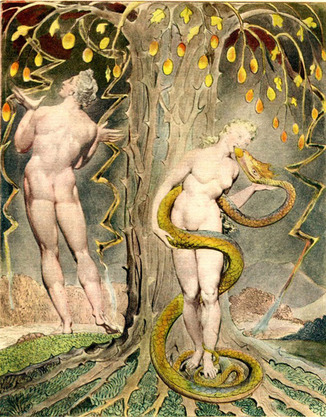

Who Needs Imagination? Common artistic portrayal of Adam, Eve, and the serpent

For those of us who grew up Christian, it's wisdom from the womb: Read your Bible, every day. As a kid, the reward for doing so was temporary amusement (guy got eaten by a fish and lived? Cool!) or nonexistent. Years later, those of us who stayed in church began to see the sense behind our parents' and pastors' dictum—delving into this ancient text deepens our faith in times of need, gives us guidance in spiritual matters, and strengthens our understanding of God throughout the ages.

Unfortunately, this seemingly simple obligation--read--is sometimes difficult to do. The great but also, sometimes tedious, thing about reading is that we can’t actually “see” the setting, scene, and characters being described to us like we can when watching a film. Instead, we must rely on our own creativity to give color and physical substance to our texts. Even when the subject at hand is painstakingly illuminated by its author, every reader envisions spatial nuances differently, so no one can be sure whether what they imagine is what was intended. If it’s hard for readers to perfectly re-create a person, place, or thing in their minds via text, then it’s nearly impossible to do when there’s nothing for the imagination to work from but a few vague, perhaps even purposefully mysterious, hints. I’m fascinated by the conundrum of how we choose to respond to things that no one living has seen first-hand. Take, for instance, the serpent. In almost every artistic depiction of the fall of Adam and Eve—where Eve is eating or picking the apple and handing it to Adam as the serpent watches on—the serpent in the scene is painted as a serpent. However, the author of Genesis leaves us with no description of the "serpent’s" original physicality. As John H. Walton points out in The Lost World of Genesis One, we modern-day Christian can’t help but view the text of the Bible through the lens of our own context. Even when that text is explicit, and contains no narrative gaps. For many Christians, reading the Bible in a certain way is paramount to being good stewards and messengers. A concordist viewpoint is admirably uncompromising—yet even for those who believe the Bible is a wholly and completely authoritative text on the nature and origin of all we see, some of the questions we consider in church simply aren’t answered by the authors of the Bible. What did that serpent look like? No one can know. Fortunately, God has given us the intellect and curiosity needed to divine answers to some of our questions through careful study of the natural world. Multiple articles in this issue of God and Nature explore different types of Bible-reading challenges. The task of interpretation lies at the end of every single Biblical story, just as it does at the conclusion of every scientific study or experiment. Since our personal experiences, prejudices, and influences inevitably shape our understanding of the divine in our universe, one of the best ways to ensure accurate readings moving forward is by questioning how we know what we know, and by challenging, sometimes even discarding, the assumptions we currently hold. God and Nature magazine now features a contact form at the end of every contribution to our magazine. Please feel welcome to challenge our own authors’ interpretations of God and nature as you read this and future issues. -Emily Ruppel |