God and Nature Spring 2022

By Janel Curry

Recently I attended a Cambridge Roundtable on Science and Religion where we discussed the limits of both scientific and religious knowledge. As I listened, I found myself uncomfortable with some of those from the faith community who were willing to put a firm line between the necessity of “blind” faith and verifiable truth. I found myself arguing for an evidence-based faith. This has led me to ponder the need for more discussion around evidence, ways of knowing, and truth claims in terms of context and limits—more explicit statements on the limits of our understanding, especially around theological, social science, and natural science claims on truth and knowledge.

Recently I attended a Cambridge Roundtable on Science and Religion where we discussed the limits of both scientific and religious knowledge. As I listened, I found myself uncomfortable with some of those from the faith community who were willing to put a firm line between the necessity of “blind” faith and verifiable truth. I found myself arguing for an evidence-based faith. This has led me to ponder the need for more discussion around evidence, ways of knowing, and truth claims in terms of context and limits—more explicit statements on the limits of our understanding, especially around theological, social science, and natural science claims on truth and knowledge.

Social science claims on truth are rightly framed with careful statements on what can be deduced from research and the limits of what the data show. |

Most theological truth claims are based on arguments that attempt to establish them as more probable than other possible competing claims. They are “tested” through the use of biblical texts, interpreting their relative significance, and relying on both the accuracy of interpretation and the weight of a theological tradition to ground the claims. Theological beliefs are not merely beliefs that must be taken on faith and cannot be “known.” Likewise, a persuasive philosophical argument is not just persuasive because it meets the standard for testing that is required by positivist social science. The mistake of many Christians along with social and natural scientists is their assumption that theological or rhetorical ways of knowing cannot be tested. In the end, all knowing involves an act of faith, whether it is trusting the evidence of our eyes and ears, or the methods of a particular discipline (Newbigin 1989, 19). When we believe something, we take on the commitment to put that belief into the public square to be tested through publishing it, sharing it, and inviting others to judge it so that it might be corrected (Newbigin 1989, 22). Those that believe they “know” something, whether through rhetorical methods or positivist social science methods, are responsible for seeking as far as possible to ensure that their truth claims are true, and true for all. But this search for truth is never finished. We are forever grasping for what is real and true for all humanity (Newbigin 1989, 23).

Social and natural science methods are similar to theological and rhetorical methods to the extent that they are both embedded within and recognize the authority of a tradition and its “ways of knowing.” Truth claims that fall clearly outside the tradition are not considered seriously. On the other hand, claims that arise out of the tradition, in dialogue with it and interpreting it, also modify the tradition. This is true whether it is the positivist tradition of the social and natural sciences, or theological truths that must be subject to discussions and debate within the Christian community. In this way, communities as a whole move toward more nuanced and complete understandings of reality (Newbigin 1989, 50).

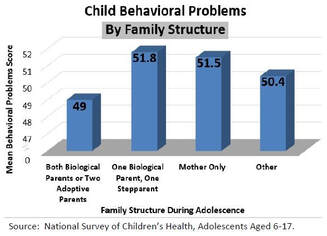

Problems occur when theological truth claims are connected with social or natural science evidence and claims without understanding or nuance. For example, social research shows that children do better when they are raised in two-parent homes. These findings come out of the methods and epistemology of positivist social sciences. What this means is that in large survey data sets, children from homes that have experienced divorce do not do as well in particular ways as children from homes with the parental marriage intact, at a statistically significant level—beyond what we would randomly find in the population. The problem comes in the translation of this “truth” to individual cases within the church. The research is showing a statistical relationship between two factors in a large data set. This is not a claim on what any one individual experiences, nor a basis for individual actions. No controlled experiment exists where you can simultaneously raise the same children in a home with both of their parents, and with only one of their parents at the same time, to judge the better result. Social science research is not making a claim about a particular situation. Furthermore, it cannot separate out the compounding factor of the cause of the stresses in the children being the same stress that causes the end of the marriage. Those children who are in intact marriages should do better because those marriages are most likely healthier marriages. And this tells us that we need to support the development of healthy marriages and families.

This distinction explains how individuals can hold high views of marriage yet be supportive of someone who is going through a divorce, or more so, go through a divorce themselves. This is not a contradiction, but rather a deeper understanding of how we seek truth at different scales and in different contexts, and then seek to apply that truth. We need all these truths on our journey toward the ultimate truth.

Social science claims on truth are rightly framed with careful statements on what can be deduced from research and the limits of what the data show. These statements attempt to keep others from drawing conclusions that go beyond the narrow claims of the study. Christians tend to over-generalize social science findings—they take narrowly defined quantitatively measured relationships and apply them beyond what has been asserted, often to back up theological truths. Rather than let these “truths” stand with their limits, churches mistakenly use these claims to make value judgments on individual cases, undermining both the theological and social science truths that have validity. We all work out of a framework of seeking to test verifiable truth within the contexts of the limits of the data sets we have. I would argue that this is why theological understanding benefits greatly from dialogues that involve theologians from around the world. We lose understanding without a breadth of experiences, just as we lose understanding when we do not incorporate all methods into our search for truth.

Social and natural scientists must also push the limits of their own methodologies to expand our understanding of human/environment relations. This area is one of great methodological challenges, and there is a theological argument for the need for greater understanding. Humans are both made in the image of God and part of God’s good creation. Humans live within the limits of nature.

How do we study this created wholeness? Take the example of agriculture. Experimental research in agriculture reduces reality into individual components and then does experiments, controlling for variables (water, soil, chemicals, heat, etc.). In reality, however, farmers make decisions in the context of variability of weather, soils, topography, distances from markets, global markets and policy, as well as social contexts. The goal should not be universally applicable theory, but a “thick understanding.” Such results help us understand other people and places; however, their complexity cannot be reduced to causal relationships that are universally applicable. The data collection in this study might include quotations, descriptions of observations, interviews, focus groups, and excerpts from documents. From the data there emerge themes, categories, and case examples. From these, we have findings, insights, and understandings that are assessed for reliability through a variety of methods. Scholars can work as teams. Multiple team members read field notes, documents, etc., and come away with different concepts/ideas. Explicit identification of procedures, assumptions, and techniques to be used can be established prior to carrying out the research.

Finally, researchers can return to the members of the group being studied and have someone who is in the setting read the work and see if it captures his/her worldview. In other words, does the analysis resonate? These findings are compared and contrasted with previous research findings as part of the journey toward developing, questioning, and refining or discarding information as it arises. Cross-validating data through the use of a variety of approaches and data types heightens the study’s reliability and dependability. This approach not only provides access to the world of the participants, but it also increases the researchers’ understanding of participants and potentially changes the researchers themselves.

A Christian approach to knowledge must also include practitioners and experience at the level where knowledge is embodied and applied. Surely the model of God becoming human illustrates this needed aspect of the journey toward understanding. Knowledge is embodied in complex relationships that incorporate the physical reality, social reality, and spiritual reality. And it is lived out in real places as wholes.

Several concepts in my discipline of geography have developed that attempt to capture the natural and human element of reality. The first of such concepts is hybridity, the idea that reality cannot be strictly divided between the natural and the human, but rather is a hybrid—part social/part natural. Key to understanding this hybridity is the role of boundary organizations: organizations that operate between the human and natural components of a natural resource. These organizations, such as irrigation districts, regional planning agencies, or hospital ethics boards, exist at the level at which multi-faceted knowledge and understanding is applied. Could the ASA, with its mission to grow its members’ understanding of faith and science and serve the church, become a rich boundary organization that brings together natural and social scientists, theologians and philosophers, and practitioners such as pastors, medical professionals, and environmentalists in order to stretch our understanding of the whole of the world that God has created?

This journey toward knowing is never done. The journey is richest if taken in the context of multiple and overlapping communities of knowledge that are encountered along the way. As we travel, we ought to be reminded of our need to exhibit humility and extreme honesty in setting the parameters of what we are claiming to know and their limited implications, grounded in rich sets of evidence of many kinds. And we can assume that we are going to be radically changed through our taking on the journey.

References

This essay draws on material from a previously published article: Curry, Janel. 2006. “Truth Claims and the Ministry of the Contemporary Church.” Perspectives: A Journal of Reformed Thought. 21 (7):11-16.

Newbigin, Lesslie. The Gospel in a Pluralistic Society (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1989).

Janel Curry is a member of the Executive Council of the ASA and an independent consultant. She previously served as interim vice president for academic affairs at Medaille College and as provost at Gordon College. Prior to Gordon, she served as dean for research and scholarship and as a faculty member at Calvin College. She has a PH.D. in geography from the University of Minnesota and a BA from Bethel in Minnesota. She has published extensively on human-land relations and environmental policy.

Social and natural science methods are similar to theological and rhetorical methods to the extent that they are both embedded within and recognize the authority of a tradition and its “ways of knowing.” Truth claims that fall clearly outside the tradition are not considered seriously. On the other hand, claims that arise out of the tradition, in dialogue with it and interpreting it, also modify the tradition. This is true whether it is the positivist tradition of the social and natural sciences, or theological truths that must be subject to discussions and debate within the Christian community. In this way, communities as a whole move toward more nuanced and complete understandings of reality (Newbigin 1989, 50).

Problems occur when theological truth claims are connected with social or natural science evidence and claims without understanding or nuance. For example, social research shows that children do better when they are raised in two-parent homes. These findings come out of the methods and epistemology of positivist social sciences. What this means is that in large survey data sets, children from homes that have experienced divorce do not do as well in particular ways as children from homes with the parental marriage intact, at a statistically significant level—beyond what we would randomly find in the population. The problem comes in the translation of this “truth” to individual cases within the church. The research is showing a statistical relationship between two factors in a large data set. This is not a claim on what any one individual experiences, nor a basis for individual actions. No controlled experiment exists where you can simultaneously raise the same children in a home with both of their parents, and with only one of their parents at the same time, to judge the better result. Social science research is not making a claim about a particular situation. Furthermore, it cannot separate out the compounding factor of the cause of the stresses in the children being the same stress that causes the end of the marriage. Those children who are in intact marriages should do better because those marriages are most likely healthier marriages. And this tells us that we need to support the development of healthy marriages and families.

This distinction explains how individuals can hold high views of marriage yet be supportive of someone who is going through a divorce, or more so, go through a divorce themselves. This is not a contradiction, but rather a deeper understanding of how we seek truth at different scales and in different contexts, and then seek to apply that truth. We need all these truths on our journey toward the ultimate truth.

Social science claims on truth are rightly framed with careful statements on what can be deduced from research and the limits of what the data show. These statements attempt to keep others from drawing conclusions that go beyond the narrow claims of the study. Christians tend to over-generalize social science findings—they take narrowly defined quantitatively measured relationships and apply them beyond what has been asserted, often to back up theological truths. Rather than let these “truths” stand with their limits, churches mistakenly use these claims to make value judgments on individual cases, undermining both the theological and social science truths that have validity. We all work out of a framework of seeking to test verifiable truth within the contexts of the limits of the data sets we have. I would argue that this is why theological understanding benefits greatly from dialogues that involve theologians from around the world. We lose understanding without a breadth of experiences, just as we lose understanding when we do not incorporate all methods into our search for truth.

Social and natural scientists must also push the limits of their own methodologies to expand our understanding of human/environment relations. This area is one of great methodological challenges, and there is a theological argument for the need for greater understanding. Humans are both made in the image of God and part of God’s good creation. Humans live within the limits of nature.

How do we study this created wholeness? Take the example of agriculture. Experimental research in agriculture reduces reality into individual components and then does experiments, controlling for variables (water, soil, chemicals, heat, etc.). In reality, however, farmers make decisions in the context of variability of weather, soils, topography, distances from markets, global markets and policy, as well as social contexts. The goal should not be universally applicable theory, but a “thick understanding.” Such results help us understand other people and places; however, their complexity cannot be reduced to causal relationships that are universally applicable. The data collection in this study might include quotations, descriptions of observations, interviews, focus groups, and excerpts from documents. From the data there emerge themes, categories, and case examples. From these, we have findings, insights, and understandings that are assessed for reliability through a variety of methods. Scholars can work as teams. Multiple team members read field notes, documents, etc., and come away with different concepts/ideas. Explicit identification of procedures, assumptions, and techniques to be used can be established prior to carrying out the research.

Finally, researchers can return to the members of the group being studied and have someone who is in the setting read the work and see if it captures his/her worldview. In other words, does the analysis resonate? These findings are compared and contrasted with previous research findings as part of the journey toward developing, questioning, and refining or discarding information as it arises. Cross-validating data through the use of a variety of approaches and data types heightens the study’s reliability and dependability. This approach not only provides access to the world of the participants, but it also increases the researchers’ understanding of participants and potentially changes the researchers themselves.

A Christian approach to knowledge must also include practitioners and experience at the level where knowledge is embodied and applied. Surely the model of God becoming human illustrates this needed aspect of the journey toward understanding. Knowledge is embodied in complex relationships that incorporate the physical reality, social reality, and spiritual reality. And it is lived out in real places as wholes.

Several concepts in my discipline of geography have developed that attempt to capture the natural and human element of reality. The first of such concepts is hybridity, the idea that reality cannot be strictly divided between the natural and the human, but rather is a hybrid—part social/part natural. Key to understanding this hybridity is the role of boundary organizations: organizations that operate between the human and natural components of a natural resource. These organizations, such as irrigation districts, regional planning agencies, or hospital ethics boards, exist at the level at which multi-faceted knowledge and understanding is applied. Could the ASA, with its mission to grow its members’ understanding of faith and science and serve the church, become a rich boundary organization that brings together natural and social scientists, theologians and philosophers, and practitioners such as pastors, medical professionals, and environmentalists in order to stretch our understanding of the whole of the world that God has created?

This journey toward knowing is never done. The journey is richest if taken in the context of multiple and overlapping communities of knowledge that are encountered along the way. As we travel, we ought to be reminded of our need to exhibit humility and extreme honesty in setting the parameters of what we are claiming to know and their limited implications, grounded in rich sets of evidence of many kinds. And we can assume that we are going to be radically changed through our taking on the journey.

References

This essay draws on material from a previously published article: Curry, Janel. 2006. “Truth Claims and the Ministry of the Contemporary Church.” Perspectives: A Journal of Reformed Thought. 21 (7):11-16.

Newbigin, Lesslie. The Gospel in a Pluralistic Society (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 1989).

Janel Curry is a member of the Executive Council of the ASA and an independent consultant. She previously served as interim vice president for academic affairs at Medaille College and as provost at Gordon College. Prior to Gordon, she served as dean for research and scholarship and as a faculty member at Calvin College. She has a PH.D. in geography from the University of Minnesota and a BA from Bethel in Minnesota. She has published extensively on human-land relations and environmental policy.