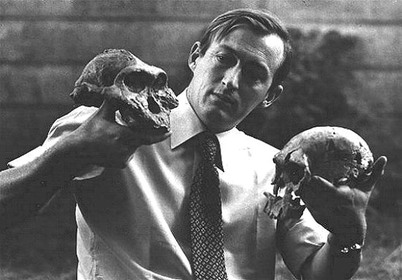

Exploring Prejudice with Richard Leakey

by Fred Heeren

I had just spent a week camping in the desert near Lake Turkana, Kenya, with “the hominid gang,” the fossil hunters led by Richard’s wife Meave and daughter Louise Leakey. I had found a missionary pilot to take me from their camp down to visit Richard in Nairobi, normally a four-day drive. Richard had lost both legs in a plane crash, but was still active in raising money to build a new, year-round field station at Lake Turkana (a story I was reporting for Scientific American). We began and ended that 2007 interview talking about Christianity. When I asked about how his grandparents came to Kenya, Richard explained how his grandfather arrived in 1901 as a missionary hoping to make Christian converts. He also intended to bring education and health to people who, until that time, had had no contact with western technology or religion. Richard’s father Louis had grown up with the Kikuyu tribe, speaking their language and learning to track and bow hunt with them. Richard described his father as “religious,” but noted that the value he’d seen in the early Genesis story had little to do with its literal interpretation. Richard’s own experience with Christianity had been less than congenial. On his first day in a “Christian” boarding school, a group of boys threw him into a cage, padlocked it, and then proceeded to spit and pee on him. Their reason? “My professed acceptance about the equality of Blacks and Whites,” he said, a cause his father had become known for—and that Richard was quick to defend. I asked how much that incident affected his thinking about Christianity. “It wasn’t the boys,” said Richard, “so much as the fact that we boys were all compelled to attend chapel and to appear to be believers. My stubbornness to say I didn’t believe and didn’t wish to believe made it worse. And it was heightened by the fact that my uncle was the Archbishop of East Africa at the time. And so I was often pointed out as an example of a somewhat abhorrent little boy who couldn’t see. I just deeply resented being forced to believe anything. And I just couldn’t understand how one was extolled to be honest and at the same time extolled to profess something one didn’t believe in. It seemed to me to be a contradiction.” Richard looked at me to see if I saw the contradiction, and I certainly did. And we agreed that the contradiction continues to be imposed upon many today. In contrast, Jesus continually challenged people to make a personal choice about coming to him, believing on him, following him; and I pointed out that of all the religions, Christianity is perhaps most pointless when coerced. We spent most of that interview talking about the discoveries that had made his father and mother, and then him and Meave, famous: the Acheulean biface tools, Zinjanthropus (Australopithecus boisei), the Black Skull (Australopithecus aethiopicus), Skull 1470 (and other specimens of Homo habilis), Turkana Boy (the most complete Homo erectus), and Omo I and II (oldest Homo sapiens skulls, now dated to 195,000 years ago). Louis Leakey had led a movement to show that Darwin was right to propose Africa as the birthplace of humanity. “There was a somewhat Caucasian-centric bias looking for Man [on other continents] and hoping that Darwin had been wrong,” said Richard. “The concept of black Africans being this sort of sub-human was only in the recent past.” One kind of prejudice leading to another, we ended up talking about the mystery of a first-world country like the U.S. continuing to have a majority that rejects evolution out of hand. The fault seems most traceable to the preachers, and I admitted that too many of them present their flocks with a false dichotomy: God or evolution. Like telling people to choose between Christ and photosynthesis. “They need to see Turkana Boy,” said Richard. “Turkana Boy is not a hypothesis. He’s a fact.” It hit me more powerfully than it had up till then that by wasting people’s time with a false choice, those pastors were keeping millions from thinking about the real one: Should we believe that we evolved without purpose? Or should we believe that God unfolded his plans over 14 billion years to the point where our ancestors became volitional beings, bringing us into an amazingly special time and place, so that we could exercise some choice about our individual roles in His grand plan? In scientific terms, this is not a typical day on Planet Earth, and the age of third-generation suns and rocky planets is not a typical day in the cosmos. We occupy a tiny slice of the whole—the slice that contains literature, love, and laughter; momentous acts of humanity as well as those of “inhumanity.” Everything that makes this planet recognizable to us—the way it’s been transformed by agriculture, the billions of people now inhabiting it, the buildings, the cities, the cultivated food, the music, the entertainment—we had none of that for almost the entire time that Homo sapiens was on this planet—maybe two hundred thousand years, about the time of Omo I and II—until the last ten thousand. And we’ve only had modern technology in the last tiny slice of that. The Psalmists agree that humanity appears insignificant, both in the amount of space we occupy compared to the rest of the universe, and the amount of time taken by a human life. But here’s where our prejudice comes into play once again. Our ignorance of the rest of time prejudices us against recognizing the significance of this one. Tennyson knew better: “I the heir of all the ages, in the foremost files of time.” Paul speaks of this little age as “the fullness of time,” and Jesus describes it with a phrase that means “the moment of ripeness.” Maybe even those of us who consider our lives most humdrum are, in truth, living at the right instant in geologic history to ask ourselves the question asked of Queen Esther: “Who knows but that you have come to this royal position for such a time as this?” — Fred Heeren |